Echoes in the Earth: Unearthing 15,000 Years of Native American Civilizations

Beneath the soil of North America lies an epic narrative, a testament to human ingenuity, adaptation, and resilience spanning millennia. Long before the arrival of European explorers, this continent was home to a vibrant tapestry of Indigenous cultures, societies, and civilizations whose histories are now meticulously pieced together through the patient work of archaeologists. These ancient peoples left behind no written records in the European sense, but their stories are etched into the landscape – in the tools they crafted, the mounds they built, the settlements they inhabited, and the very earth they shaped.

Understanding Native American archaeological periods is crucial to appreciating the immense depth and diversity of Indigenous history. It’s a journey that takes us from ice-age hunters tracking megafauna to complex agricultural societies building monumental cities, offering a profound counter-narrative to the often-simplified portrayals of pre-Columbian America.

The First Footprints: The Paleo-Indian Period (c. 15,000 – 8,000 BCE)

The story begins in the chill of the last Ice Age, an era known as the Paleo-Indian period. This was a time of vast glaciers, dramatically different coastlines, and a landscape teeming with now-extinct megafauna like woolly mammoths, mastodons, and saber-toothed cats. The earliest inhabitants of North America were nomadic hunter-gatherers, following these immense game animals across a continent that was still largely unpopulated by humans.

For decades, the Clovis culture, named after distinctive fluted spear points first discovered near Clovis, New Mexico, was considered the definitive evidence of the continent’s earliest human presence, dating back roughly 13,500 years ago. These exquisitely crafted projectile points, designed to be hafted onto spears, were highly effective against large game. The widespread distribution of Clovis artifacts across North America suggested a rapid and efficient colonization of the continent.

However, archaeological discoveries in recent decades have challenged this "Clovis First" paradigm. Sites like Monte Verde in Chile, dating back over 14,500 years, and evidence from more controversial sites like the Paisley Caves in Oregon or the Topper Site in South Carolina, hint at a pre-Clovis presence. These findings suggest that the initial peopling of the Americas was likely a more complex process, possibly involving multiple waves of migration, different routes (including a coastal migration route), and diverse technologies. As Dr. Dennis Stanford, a leading proponent of a potential European Solutrean connection, once mused, "The more we look, the more complex the story becomes." The exact timing and pathways of these first Americans remain a subject of active debate and ongoing research, but what is clear is their incredible adaptability and skill in navigating a challenging new world.

A World of Adaptation: The Archaic Period (c. 8,000 – 1,000 BCE)

As the glaciers retreated and the climate warmed, the megafauna began to disappear, ushering in the Archaic period. This era marked a profound shift in human adaptation, as people began to exploit a much broader spectrum of resources. Gone were the specialized megafauna hunters; in their place emerged highly localized and diverse cultures, each expertly attuned to their specific regional environments.

Archaic peoples became adept at hunting smaller game like deer, elk, and rabbit, fishing in rivers and coastal waters, and gathering a wide variety of wild plants, nuts, and seeds. This "broad-spectrum foraging" led to the development of new tools: grinding stones for processing plant foods, fishhooks, nets, and the atlatl (spear thrower), which increased the power and accuracy of projectile weapons.

Sedentism, or living in more permanent settlements, began to increase, particularly in resource-rich areas. This period also saw the earliest hints of plant domestication in North America, with cultures in the Eastern Woodlands cultivating native squash, gourds, and sunflowers long before the arrival of maize from Mesoamerica.

One of the most remarkable Archaic sites is Poverty Point in Louisiana, dating to around 1700-1100 BCE. This monumental complex consists of six concentric earthen ridges forming a series of C-shaped rings, along with several large mounds. It’s an astounding feat of engineering for a society that was still primarily hunter-gatherer, indicating a sophisticated level of social organization and labor mobilization. As archaeologist Jon L. Gibson describes it, Poverty Point was "a vast complex of earthworks that still defies easy explanation," suggesting a communal purpose, perhaps for trade, ceremony, or seasonal gatherings, that drew people from hundreds of miles away. The site stands as a powerful testament to the complexity and communal spirit of Archaic societies.

The Dawn of Complexity: The Woodland Period (c. 1,000 BCE – 1,000 CE)

The Woodland period witnessed a significant acceleration in cultural complexity, characterized by three major innovations: the widespread adoption of pottery, the construction of elaborate burial mounds, and the increasing reliance on horticulture.

Pottery, which allowed for more efficient cooking and storage of food, revolutionized daily life. Its stylistic variations also provide archaeologists with crucial markers for distinguishing different cultural groups and tracing their movements and interactions.

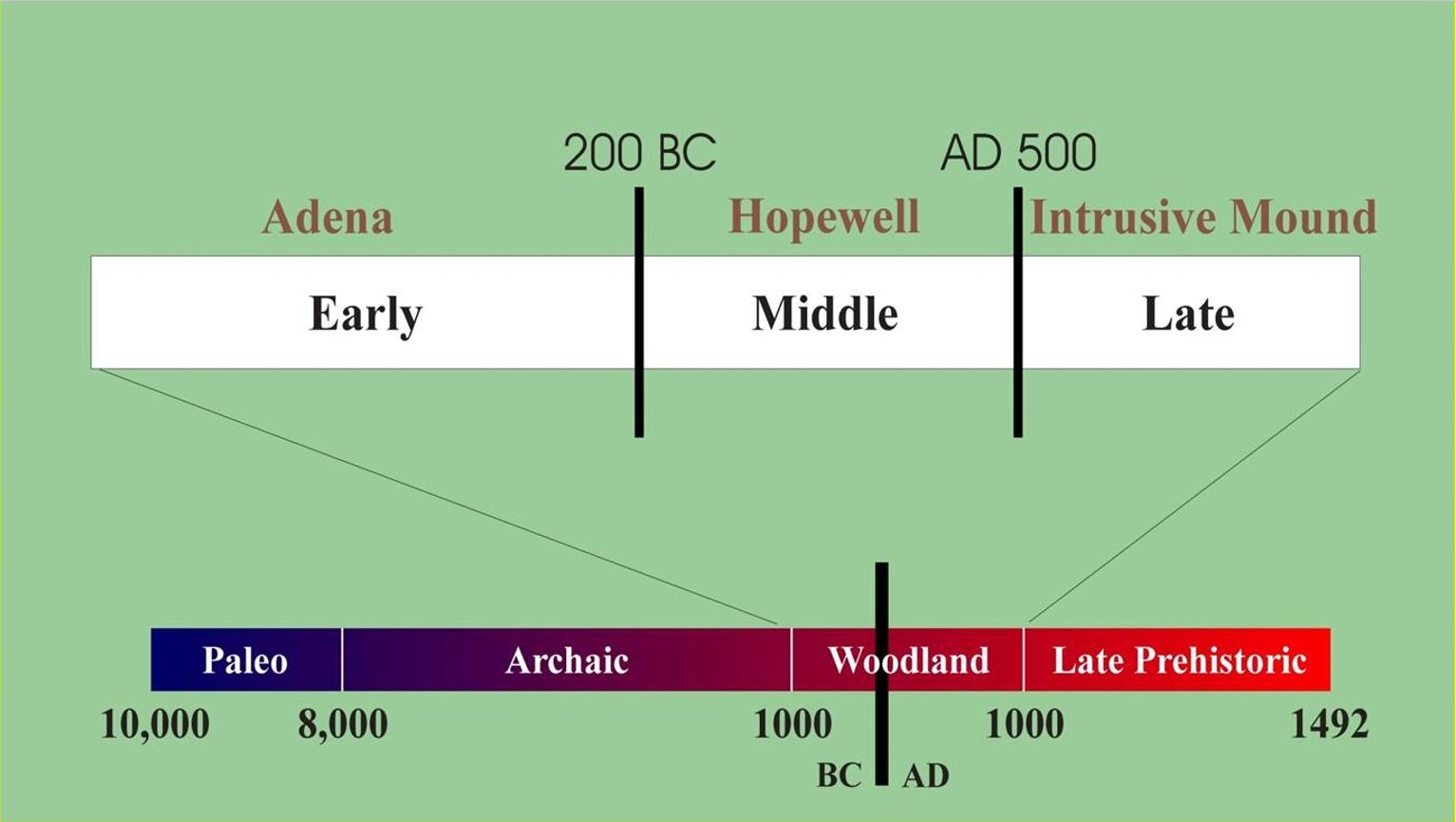

Mound building, though present in the late Archaic, truly flourished during the Woodland period. Two prominent cultures, the Adena (c. 800 BCE – 100 CE) and the Hopewell (c. 200 BCE – 500 CE), are particularly known for their impressive earthworks in the Ohio River Valley. Adena mounds were often conical and served as burial sites for important individuals, sometimes containing elaborate grave goods. The Hopewell, however, took mound building to an entirely new level. Their complexes featured enormous geometric earthworks – circles, squares, and octagons – often aligned with celestial events, suggesting a sophisticated understanding of astronomy and a complex ceremonial life.

The "Hopewell Interaction Sphere" is a concept used to describe the vast trade networks that connected communities across much of eastern North America. Exotic materials like obsidian from the Yellowstone area, copper from the Great Lakes, mica from the Appalachian Mountains, and shells from the Gulf Coast were exchanged over immense distances, often finding their way into Hopewell burial mounds. This extensive exchange system speaks to a shared ideology and a desire for prestige goods, fostering a degree of cultural homogeneity over a broad geographical area without necessarily implying a unified political entity. As archaeologist Brad Lepper notes, "The Hopewell were not an empire, but their influence was felt far and wide, connecting diverse peoples through shared ideas and valuable goods."

The Rise of Cities: The Mississippian Period (c. 900 – 1600 CE)

The Mississippian period represents the pinnacle of prehistoric social and political complexity in eastern North America. It was fundamentally shaped by the widespread adoption and intensive cultivation of maize (corn), which had slowly made its way north from Mesoamerica over centuries. Maize agriculture provided a stable and abundant food supply, capable of supporting larger, denser populations and fostering the development of stratified societies.

Mississippian societies were characterized by the emergence of powerful chiefdoms, hierarchical social structures, and the construction of monumental platform mounds, which served as foundations for temples, elite residences, and ceremonial buildings. These chiefdoms often controlled vast territories, engaging in both trade and warfare with neighboring groups.

The most spectacular example of a Mississippian center is Cahokia, located near modern-day St. Louis, Missouri. At its peak around 1050-1200 CE, Cahokia was larger than London was at the same time, with a population estimated to be between 10,000 and 20,000 people, making it the largest pre-Columbian city north of Mexico. Its central feature, Monks Mound, is the largest earthen structure in North America, covering 14 acres and rising 100 feet. It required an estimated 22 million cubic feet of earth to construct, all moved by hand in baskets.

Cahokia was a bustling metropolis, a center of religious, political, and economic power. Its influence radiated outward, and its intricate social system, elaborate rituals, and sophisticated urban planning continue to amaze archaeologists. Dr. Timothy Pauketat, a leading Cahokia scholar, famously described it as "a city of the sun," highlighting its astronomical alignments and its people’s deep connection to the cosmos. The sudden decline of Cahokia after 1200 CE, perhaps due to environmental degradation, internal conflict, or disease, remains one of archaeology’s enduring mysteries.

The Crossroads: The Protohistoric and Contact Periods (c. 1500 – 1700 CE)

The Protohistoric period bridges the gap between purely archaeological understanding and the first written accounts from European explorers and colonists. This era, beginning roughly in the 16th century, was a time of immense, often devastating, change for Native American societies. While Europeans had not yet established widespread settlements, their presence was felt far inland through the spread of trade goods (like metal tools and glass beads), new diseases, and political upheavals.

Archaeology in this period often works in conjunction with historical documents, though it critically provides the Indigenous perspective that is often missing from early European records. It reveals how Native communities adapted to new challenges, incorporating European goods into their existing economies, sometimes migrating to form new alliances, and frequently facing unprecedented mortality rates due to diseases like smallpox, measles, and influenza, to which they had no immunity. Entire populations were decimated, and the social and political landscapes of continents were irrevocably altered.

The Contact period, marking the direct and sustained interaction between Native Americans and Europeans, is characterized by escalating trade, land dispossession, warfare, and cultural clashes. Archaeological sites from this era often contain a mix of Indigenous and European artifacts, reflecting the complex processes of exchange, resistance, and adaptation. These sites tell stories of resilience, as Native peoples fought to maintain their cultures and sovereignty in the face of overwhelming pressure.

A Legacy Uncovered

The archaeological record of Native American periods is a dynamic and ever-expanding narrative. It reveals a history of continuous innovation, profound spiritual connections to the land, sophisticated social structures, and incredible artistic expression. From the spear points of the Paleo-Indians to the monumental mounds of the Mississippians, each artifact, each excavated layer, adds another brushstroke to a vast and intricate canvas.

Archaeology is not merely about unearthing relics; it is about giving voice to the ancestors, challenging misconceptions, and enriching our collective understanding of human history. It reminds us that North America was not an empty wilderness awaiting discovery, but a continent teeming with diverse and complex civilizations, whose legacies continue to shape the land and its peoples today. As we continue to dig, to analyze, and to listen to the echoes in the earth, we gain a deeper appreciation for the enduring spirit and profound contributions of Native American cultures.