Echoes in the Golden Hills: The Enduring Spirit of the Palouse Tribe

The rolling hills of the Palouse, a vast ocean of wheat and lentil fields stretching across southeastern Washington and northern Idaho, are often celebrated for their unique geological formations and agricultural bounty. Yet, beneath this cultivated landscape, and within the deep canyons carved by the Snake and Columbia Rivers, lies a story far older and more profound – the enduring narrative of the Palouse Tribe, the original inhabitants and stewards of this remarkable land. Their history is one of deep connection to place, formidable horsemanship, quiet resilience, and a persistent struggle for recognition in a world that often rendered them invisible.

For millennia, long before the arrival of European explorers and settlers, the Palouse people, or Palus as they called themselves, thrived in a territory that encompassed the fertile Palouse River valley, the Snake River’s confluence with the Columbia, and vast tracts of the surrounding plateau. As members of the larger Sahaptin-speaking Plateau cultures, their lives were intricately woven into the rhythms of the land and its abundant resources. Their name, "Palus," is believed to derive from the Sahaptin word palú:s, referring to "something standing in the water," likely referencing a prominent rock or the Palouse River itself. This name is a testament to their deep-rooted identity with the waterways that sustained them.

The Palouse were semi-nomadic, moving with the seasons to harvest nature’s bounty. The lifeblood of their existence was the anadromous salmon, which returned in prodigious numbers to the Columbia and Snake Rivers. Expert fishers, they employed intricate weirs, nets, and spears, curing vast quantities of salmon for year-round sustenance. Beyond fishing, they were skilled hunters, pursuing deer, elk, and waterfowl across the plateau. Gathering was equally vital, with women harvesting camas roots – a starchy, nutrient-rich staple baked in earthen ovens – along with berries, bitterroot, and other plants that provided both food and medicine.

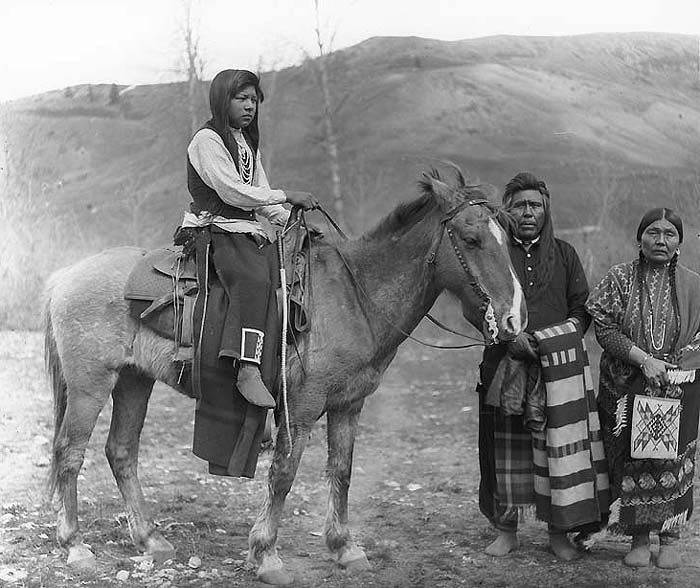

However, it was the horse that truly transformed the Palouse way of life and cemented their legendary status. Introduced to the region in the early 18th century, horses rapidly became central to their culture, economy, and identity. The Palouse became master horse breeders and riders, developing a distinct breed known for its stamina, intelligence, and unique spotted coat: the Appaloosa. "The Appaloosa, with its distinctive spotted coat, is not merely a breed of horse; it is a living testament to the Palouse people’s deep equestrian heritage," notes a contemporary historian. This magnificent animal facilitated wider hunting grounds, expanded trade networks that stretched across the continent, and enhanced their military prowess. Their equestrian skill was renowned, allowing them to travel vast distances, participate in bison hunts on the Great Plains, and engage in intricate social and political relationships with neighboring tribes like the Nez Perce, Cayuse, Yakama, and Umatilla.

The arrival of Lewis and Clark in 1805 marked the beginning of profound changes. The explorers encountered a people of impressive horsemanship and a sophisticated culture. Initial interactions were generally amicable, characterized by curiosity and exchange. However, this peaceful coexistence was short-lived. The subsequent influx of fur traders, missionaries, and eventually, a torrent of American settlers, brought disease, competition for resources, and an inexorable pressure on Palouse lands and traditions.

The mid-19th century proved to be a pivotal and devastating period. The U.S. government, driven by the ideology of Manifest Destiny, sought to "civilize" and confine Native peoples to reservations. The Treaty of Walla Walla in 1855, intended to consolidate land cessions from various Plateau tribes, stands as a critical juncture in Palouse history. While many neighboring tribes signed the treaty, often under duress, numerous Palouse bands steadfastly refused, viewing the land as inalienable and resisting the notion of surrendering their ancestral homelands. This refusal meant that, unlike many other tribes, the Palouse never formally ceded their land to the U.S. government, nor were they officially assigned a specific reservation. This "un-treatied" status, while a testament to their fierce independence, would ironically lead to decades of ambiguous legal standing and a struggle for federal recognition.

Their refusal to sign the treaty, coupled with the increasing encroachment of settlers, led to escalating tensions and conflicts, including the Yakima War of 1855-1858. While some Palouse leaders, like the influential Chief Kamiakin (who was of mixed Yakama/Palouse heritage), played significant roles in resisting American expansion, other Palouse bands sought to maintain peace and autonomy.

The most poignant chapter of this era for the Palouse came during the Nez Perce War of 1877. While many Palouse had intermarried with and maintained close ties to the Nez Perce, their role in the war was complex. Some Palouse warriors joined Chief Joseph’s band in their desperate flight for freedom, fighting valiantly. Others, led by Chief Timothy (also known as Tamason or Tah-mah-han), a prominent Palouse leader, chose a path of neutrality, even assisting U.S. troops by allowing them passage through their lands and offering intelligence. Timothy’s decision, though controversial, was born of a desire to protect his people and secure their continued access to their homelands along the Snake River. Despite his cooperation, the Palouse suffered immense losses, both in terms of lives and land.

Following the Nez Perce War and the subsequent military campaigns, the Palouse people were largely dispersed. With no dedicated reservation, many were forced to seek refuge and assimilate into the larger communities of their relatives on the Nez Perce, Yakama, Umatilla, and Colville Reservations. This period of dispersal led to a significant loss of distinct Palouse identity in the eyes of the U.S. government and the general public. They became, in a sense, an "invisible" tribe, their existence often overlooked or absorbed into the narratives of larger, federally recognized entities.

Yet, the spirit of the Palouse endured. Despite the forced assimilation and the loss of their traditional lands, Palouse descendants never truly forgot their heritage. They continued to practice their traditions in quiet ways, passing down stories, songs, and knowledge of the land through generations. Their spiritual connection to places like Palouse Falls, a majestic cascade sacred in their cosmology, remained unbroken. Fishing rights, though often challenged, were fiercely guarded, and the memory of their ancestral lands persisted as a powerful cultural anchor.

In recent decades, there has been a significant resurgence of Palouse identity and a concerted effort by descendants to reclaim their heritage and seek federal recognition. This movement is driven by a deep desire to honor their ancestors, preserve their unique culture, and secure the rights and resources that come with official tribal status. For many, this involves extensive genealogical research, community building, and advocating for their history to be properly acknowledged.

"We are still here. Our ancestors never left this land; they simply became invisible to the colonizers," affirms LaRae Wiley, a prominent Palouse descendant and cultural educator, whose words resonate with the quiet determination of her people. This sentiment encapsulates the modern Palouse struggle: to make visible what was made invisible, to articulate a distinct identity that has been subsumed, and to connect the scattered descendants to a shared past and future.

The journey toward federal recognition is arduous, requiring extensive documentation and navigating complex bureaucratic processes. It is a path fraught with challenges, yet it is pursued with unwavering dedication by those who carry the Palouse bloodline. Cultural revitalization efforts are also underway, focusing on language preservation, traditional arts, and ceremonies, ensuring that the ancient knowledge of the Palouse is not lost to future generations. The Appaloosa horse, a living symbol of their history, continues to be a source of pride and a tangible link to their equestrian past.

The story of the Palouse Tribe is a powerful testament to the enduring power of culture, memory, and an unbreakable bond with the land. From their days as master horsemen and stewards of the golden hills to their quiet perseverance through centuries of displacement, the Palouse people have demonstrated a remarkable resilience. Their fight for recognition is not merely a legal battle; it is a profound act of self-determination, a declaration that their history matters, their culture is vibrant, and their presence in the Palouse country, though often unheard, is eternal. As the wind whispers through the wheat fields, it carries the echoes of the Palouse, a reminder that the land remembers its original guardians, and they, in turn, remember their unbreakable connection to it.