Echoes in the Landscape: America’s Legends, From Cryptids to Carleton

America, a nation forged from diverse peoples and a vast, untamed landscape, pulses with stories. Beyond the official histories and documented facts, a vibrant tapestry of legends weaves through its mountains, deserts, cities, and forgotten corners. These are not merely quaint folktales; they are the collective dreams and nightmares, the hopes and fears, the triumphs and profound traumas that shape the American identity. From elusive cryptids to spectral apparitions, from larger-than-life folk heroes to the stark, enduring legends of historical suffering, these narratives offer a profound glimpse into the national psyche. And sometimes, as in the tragic tale of Carleton Operations in New Mexico, these "legends" are the uncomfortable, essential truths that refuse to be forgotten.

The most whimsical, perhaps, are the legends of the unknown. Across the mist-shrouded forests of the Pacific Northwest, the elusive Bigfoot, or Sasquatch, has captivated imaginations for generations. Described as a large, hairy, bipedal ape-like creature, sightings of Bigfoot stretch back centuries, rooted in Native American folklore long before it became a staple of modern cryptid culture. The enduring appeal of Bigfoot lies in its embodiment of the wild, untamed frontier that America once was and, in some remote corners, still is. It’s a symbol of the mysteries that linger beyond the reach of human civilization, a reminder that even in an age of satellite imagery and instant information, the wilderness still holds its secrets. Footage like the famous 1967 Patterson-Gimlin film, though debated, only fuels the legend, turning blurry images into a Rorschach test for our belief in the unexplained.

Venturing further into the paranormal, the legends of ghosts and spectral phenomena are woven into the very fabric of American history. From the battlefields of Gettysburg, where spectral soldiers are said to relive their final moments, to the Winchester Mystery House in California, an architectural labyrinth built to appease vengeful spirits, the belief in the lingering dead is pervasive. These legends often serve as a way to confront grief, process historical trauma, or simply indulge in the thrill of the unknown. They remind us that history is not just a collection of dates, but a living, breathing presence that can sometimes, we are told, make itself felt in the chill of a room or the whisper of a forgotten name.

Perhaps no genre of American legend captures the nation’s anxieties and its fascination with the extraterrestrial quite like the UFO phenomenon, particularly centered around Roswell, New Mexico. In July 1947, the alleged crash of a "flying saucer" near Roswell became the epicenter of a global conspiracy theory. The official explanation – that it was a downed weather balloon – was quickly dismissed by a skeptical public and ufologists who believed a genuine alien spacecraft had crashed, and its debris and occupants were recovered and concealed by the U.S. government. Roswell became a powerful legend of government secrecy, alien visitation, and the tantalizing possibility that humanity is not alone. It tapped into post-war paranoia and a burgeoning scientific curiosity, cementing New Mexico’s place as a hotspot for the unexplained, a land where the vast, open skies might hold more than just clouds.

Beyond the cryptids and the cosmic, America also cherishes its folk heroes and tall tales. These legends, often exaggerated and larger-than-life, speak to the nation’s pioneering spirit, its industrial might, and its rugged individualism. Paul Bunyan, the colossal lumberjack with his blue ox, Babe, embodies the conquest of the American wilderness, felling entire forests with a single swing of his axe and carving out the Great Lakes with his footsteps. He is a legend of strength, ingenuity, and the sheer scale of American ambition during the era of westward expansion and industrial growth. Similarly, Johnny Appleseed (John Chapman), who tirelessly planted apple trees across the Midwest, represents the softer side of pioneering – nurturing, enduring, and leaving a legacy that feeds future generations. These legends are not just stories; they are aspirational myths, reflecting the values and dreams of a young nation building itself from the ground up.

However, not all American legends are born of wonder or aspiration. Some are born of pain, injustice, and the profound weight of history. These are the legends that challenge the romanticized narratives, forcing a confrontation with uncomfortable truths. This brings us to a crucial, often overlooked, yet deeply significant "legend" of trauma and resilience in the very heart of New Mexico: Carleton Operations, more widely known as the Fort Sumner or Bosque Redondo Reservation, and the tragic "Long Walk" of the Navajo people.

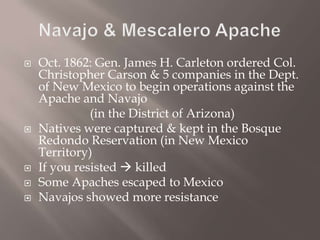

In the mid-19th century, as the United States aggressively expanded westward, its gaze fell upon the vast lands of the Navajo (Diné) people in what is now Arizona and New Mexico. Following decades of conflict, resource disputes, and broken treaties, the U.S. government, under the command of General James H. Carleton, initiated a brutal campaign to subdue the Navajo. Carleton’s strategy was simple and devastating: destroy their livelihoods, burn their crops, and force them onto a barren reservation.

The instrument of this policy was Colonel Kit Carson, a legendary frontiersman whose name often evokes images of rugged exploration and heroism. Yet, for the Navajo, Carson’s name is inextricably linked to one of the darkest chapters in their history. From 1863 to 1866, Carson and his troops systematically waged war, culminating in the destruction of the Navajo’s economic base. The ultimate goal was their forced removal to the Bosque Redondo Reservation, a desolate, 40-square-mile tract of land near Fort Sumner, New Mexico, chosen by General Carleton.

What followed was "The Long Walk" (Hwéeldi in Navajo). Between 1864 and 1866, approximately 8,000 to 10,000 Navajo men, women, and children, along with about 400 Mescalero Apache, were forcibly marched over 300 miles from their ancestral homelands to Bosque Redondo. It was a forced displacement comparable to the Cherokee Trail of Tears. The journey was harrowing. Many died from starvation, exposure, disease, and exhaustion. Soldiers often shot those who could not keep up. Accounts describe immense suffering, with bodies left unburied along the trail.

Upon arrival at Bosque Redondo, conditions were equally horrific. The land was inhospitable, with saline water and insufficient wood for shelter or fuel. The U.S. government failed to provide adequate food, clothing, or medical care. Crop failures due to pests and climate, combined with the concentration of thousands of people in a small area, led to widespread disease, malnutrition, and death. The Navajo, a people accustomed to a vast, free existence, were confined and subjected to unimaginable indignities. It was, in essence, a concentration camp designed to assimilate them by destroying their culture and spirit.

This period of incarceration lasted four long years. By 1868, the U.S. government finally acknowledged the utter failure and humanitarian catastrophe of the Bosque Redondo experiment. On June 1, 1868, the Treaty of Bosque Redondo was signed, allowing the Navajo to return to a portion of their original homeland. This was a unique event in U.S. history, as it was the only time the government permitted a Native American tribe to return to their former lands after a forced removal. The return journey, though to a familiar landscape, was still fraught with hardship, but it was a journey of hope and renewed determination.

Why is Carleton Operations and The Long Walk a "legend" of America? It is not a myth in the traditional sense, but a foundational, traumatic historical event that has attained legendary status within the Navajo nation and beyond. It is a story passed down through generations, shaping identity, fostering resilience, and serving as a constant reminder of survival against immense odds. It is a legend of the devastating consequences of manifest destiny, of cultural genocide, and of the enduring human spirit. For the Navajo, Hwéeldi is not just history; it is a living memory, an ancestral wound, and a testament to their strength and cultural persistence. It stands in stark contrast to the whimsical legends of Bigfoot or Paul Bunyan, offering a powerful counter-narrative to the often-celebratory myths of American expansion.

America’s legends, therefore, are a complex mirror reflecting its soul. From the wild frontiers symbolized by Bigfoot, to the anxieties of the unknown in Roswell, to the pioneering spirit of Paul Bunyan, these stories reveal much about the nation’s aspirations and its evolving identity. But critically, they also encompass the profound and often painful legends like that of Carleton Operations and The Long Walk. These are the narratives that challenge the romanticized past, reminding us that the American story is not monolithic. It is a mosaic of dreams and nightmares, of heroes and villains, of wonders and wounds, all echoing through the vast and varied landscapes of a continent still telling its tales. To understand America, one must listen to all its legends, for in their collective telling, the true story of the nation unfolds.