Echoes in the Oaks: The Enduring Spirit of the Miwok Indians

By [Your Name/Journalist Name]

California, a land of golden hills and towering redwoods, has long been synonymous with dreams of discovery and prosperity. Yet, beneath the veneer of its vibrant modernity lies a deeper, ancient history – a narrative etched into the very landscape by its first peoples. Among them are the Miwok Indians, whose story is not merely one of survival against immense odds, but a testament to an enduring spirit and a profound connection to their ancestral lands. From the coastal fog to the high Sierra peaks, the Miwok have lived, thrived, and adapted, their culture a vibrant thread in the tapestry of California’s past, present, and future.

For thousands of years before European contact, the Miwok, a collective of distinct linguistic and cultural groups including the Coast Miwok, Lake Miwok, Plains Miwok, and Sierra Miwok, flourished across vast swathes of what is now central California. Their territories spanned from the Pacific Coast north of San Francisco Bay, through the fertile Sacramento and San Joaquin Valleys, and into the rugged foothills and western slopes of the Sierra Nevada mountains. This diverse geography shaped their lifestyles, leading to subtle variations in customs, but all shared a deep, reciprocal relationship with the natural world.

The Miwok were consummate stewards of their environment, practicing a sophisticated form of ecological management that ensured the abundance of resources. Their lives revolved around the seasonal rhythms of hunting, fishing, and gathering. The cornerstone of their diet was the acorn, primarily from the abundant Black Oak and California Live Oak trees. This humble nut was transformed through an arduous, multi-step process: gathering, shelling, drying, pounding into flour, and then leaching out bitter tannins with water, often in sand basins. The resulting sweet, nutritious flour was then cooked into porridges, breads, or cakes. This staple provided sustenance for the majority of the year, allowing for complex social structures and the development of rich cultural practices.

"Our ancestors understood the land as a relative, not a resource," explains a contemporary Miwok elder, reflecting on traditional wisdom. "Every plant, every animal, every stream had a spirit, and we were part of that interconnected web. We didn’t take more than we needed, and we always gave thanks."

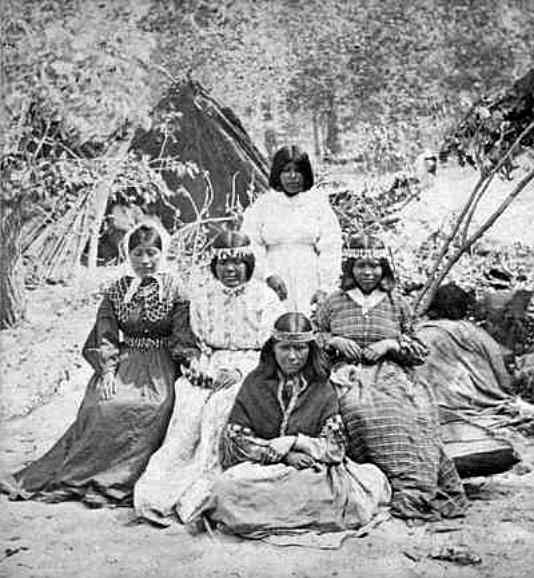

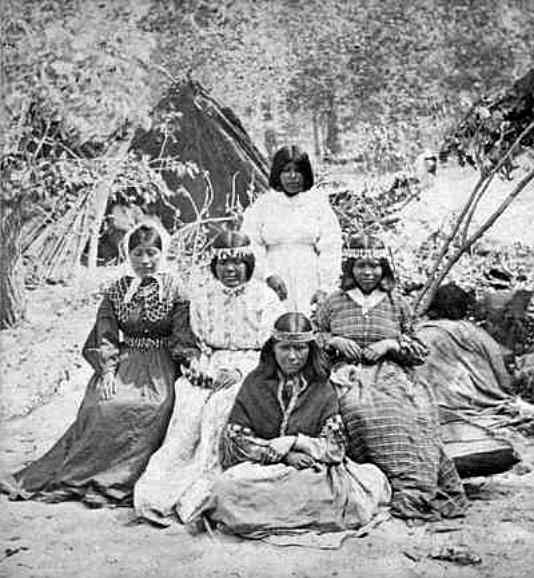

Beyond acorns, the Miwok hunted deer, elk, rabbits, and various fowl, and fished for salmon and steelhead in the region’s abundant rivers and streams. Their material culture was equally ingenious. They crafted intricate basketry from sedge, willow, and other plant fibers, so finely woven they could hold water. These baskets were not just utilitarian objects for gathering, storage, and cooking; they were exquisite works of art, imbued with spiritual significance and often decorated with geometric patterns and feathers. Dwellings varied from conical structures of bark or tule reeds to semi-subterranean earth lodges for larger community gatherings and ceremonies, particularly among the Sierra Miwok.

Socially, Miwok communities were organized into villages, each typically led by a headman or chief, whose role was often hereditary but required community consensus. Kinship ties were paramount, forming the basis of their social fabric and guiding alliances, trade, and ceremonial life. Spiritual beliefs centered on a rich cosmology, often featuring Coyote as a prominent creator and trickster figure, along with other animal spirits and natural phenomena. Ceremonies, dances, and oral traditions played vital roles in transmitting knowledge, values, and history across generations.

The equilibrium of this ancient way of life was shattered with the arrival of Europeans. The first significant impact came with the Spanish mission system in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. While some Miwok communities managed to avoid direct entanglement with the missions, many were forcibly removed from their lands, subjected to forced labor, disease, and the suppression of their traditional spiritual practices. The missions were catastrophic, decimating populations and disrupting centuries-old cultural patterns.

However, the darkest chapter for the Miwok, and indeed for most California Native Americans, was yet to come. The discovery of gold in 1848 ignited the infamous California Gold Rush. What followed was an unprecedented invasion of their lands by hundreds of thousands of fortune-seekers. The Gold Rush wasn’t just a rush for gold; it was a rush for land, and it unleashed a horrific period of violence, displacement, and cultural genocide against indigenous peoples. Miners encroached on Miwok territories, destroyed traditional food sources, and brought with them diseases to which Native populations had no immunity.

"The Gold Rush period was the bloodiest chapter in California’s history for Native Americans," states Dr. Deborah Miranda, a contemporary scholar of Ohlone and Esselen descent. "State-sanctioned militias and individual prospectors engaged in massacres, kidnappings, and enslavement with impunity. It was a deliberate attempt to remove obstacles to resource extraction." Miwok populations plummeted, their land base shrunk dramatically, and their cultural practices were driven underground for fear of violent reprisal. Treaties signed with the U.S. government were often unratified or ignored, further dispossessing them of their ancestral homelands.

Despite this devastating onslaught, the Miwok endured. They found refuge in remote areas, formed alliances, and stubbornly held onto fragments of their heritage. The late 19th and early 20th centuries saw the establishment of "rancherias," small land parcels set aside for landless Native Americans, often a fraction of their original territories. These rancherias, though meager, became vital centers for cultural survival, allowing communities to maintain some semblance of their traditional lives, often in the face of ongoing discrimination and poverty.

The mid-20th century brought another challenge: the federal policy of "termination," which sought to end the federal government’s recognition of Native American tribes and their unique relationship with the U.S. government. Many Miwok rancherias were terminated, leading to further loss of land and services. However, a powerful grassroots movement for self-determination emerged, culminating in the restoration of many terminated tribes in the 1980s and 1990s.

Today, the Miwok are a vibrant, resilient people, actively engaged in a profound cultural renaissance. Several Miwok tribal groups are federally recognized, including the Federated Indians of Graton Rancheria, the Jackson Rancheria Band of Miwuk Indians, the Tuolumne Band of Me-Wuk Indians, and the Shingle Springs Band of Miwok Indians, among others. These sovereign nations are working tirelessly to reclaim and revitalize their heritage.

Language revitalization programs are at the forefront of this effort. "Our language is the key to our culture, to our way of thinking," says a language instructor at the Tuolumne Band of Me-Wuk Indians. "When we speak Miwok, we connect directly to our ancestors and to the land." Elders, once forced to suppress their native tongues, are now revered teachers, passing on the precious lexicon to younger generations through classes, immersion programs, and digital resources.

Basketry, once nearly a lost art, is experiencing a powerful resurgence. Master weavers are teaching the intricate techniques, ensuring that the ancient knowledge of plant gathering, preparation, and weaving patterns continues. Traditional dances, songs, and ceremonies are also being revived, bringing communities together to celebrate their shared identity and spiritual connection.

Economically, many Miwok tribes have leveraged gaming enterprises to build economic stability, allowing them to fund essential services, education, healthcare, and cultural programs for their members. These ventures provide a degree of self-sufficiency that was unimaginable for generations. However, economic development is often balanced with traditional values and environmental stewardship. Tribes are increasingly involved in land management, fire prevention using traditional methods, and conservation efforts, drawing upon their ancestral ecological knowledge.

Challenges remain. Stereotypes persist, historical trauma continues to impact communities, and the fight for full sovereignty and land rights is ongoing. Yet, the Miwok stand as a powerful testament to the resilience of indigenous cultures. Their story is a crucial reminder that California’s history is not just about gold rushes and Hollywood dreams, but about the deep roots of its first peoples, who, despite unimaginable adversity, continue to thrive.

The Miwok, the "people," as their name translates in some dialects, are no longer just echoes in the oaks. They are a living, breathing testament to the enduring human spirit, their voices strong, their traditions vibrant, and their connection to the California landscape as profound as it has been for millennia. As the sun sets over the golden hills, casting long shadows from the ancient oak trees, one can almost hear the rhythmic pounding of acorns, the quiet hum of a weaver’s song, and the enduring heartbeat of a people deeply rooted in their ancestral home.