Echoes in the Palmetto: The Enduring Legacy of Florida’s Timucua Tribe

The very name "Florida" conjures images of sun-drenched beaches, bustling cities, and theme park magic. Yet, beneath the veneer of modern development, lie layers of history, whispers of forgotten peoples whose lives shaped the peninsula long before it became a tourist paradise. Among the most prominent, and tragically, most decimated, of these early inhabitants were the Timucua. A vibrant, complex tapestry of chiefdoms, they once commanded a vast swath of land across northern Florida and southern Georgia, their culture flourishing for millennia before the arrival of European sails irrevocably altered their destiny.

The story of the Timucua is not merely a chapter in Florida’s past; it is a profound testament to human resilience, cultural richness, and the devastating impact of colonial encounter. It is a narrative woven with threads of sophisticated societal structures, intricate spiritual beliefs, advanced agricultural practices, and ultimately, a tragic decline that saw a populous and powerful people virtually vanish from the historical record as a distinct entity. Yet, their legacy endures, etched into the landscape, unearthed by archaeologists, and preserved in the few precious accounts left by the very Europeans who precipitated their downfall.

A Flourishing Pre-Columbian World

Before the 16th century, the Timucua were the dominant indigenous group in what would become northern Florida, their territories stretching from the Atlantic coast westward to the Aucilla River and northward into Georgia. They were not a single, unified "tribe" in the modern sense, but rather a collection of some 35 distinct chiefdoms, each with its own leader, customs, and dialect, yet sharing a common language family – Timucuan – and a broadly similar cultural framework. Among the most prominent of these chiefdoms were the Utina, Saturiwa, Potano, and Fresh Water peoples, each vying for influence and often engaging in complex alliances and conflicts.

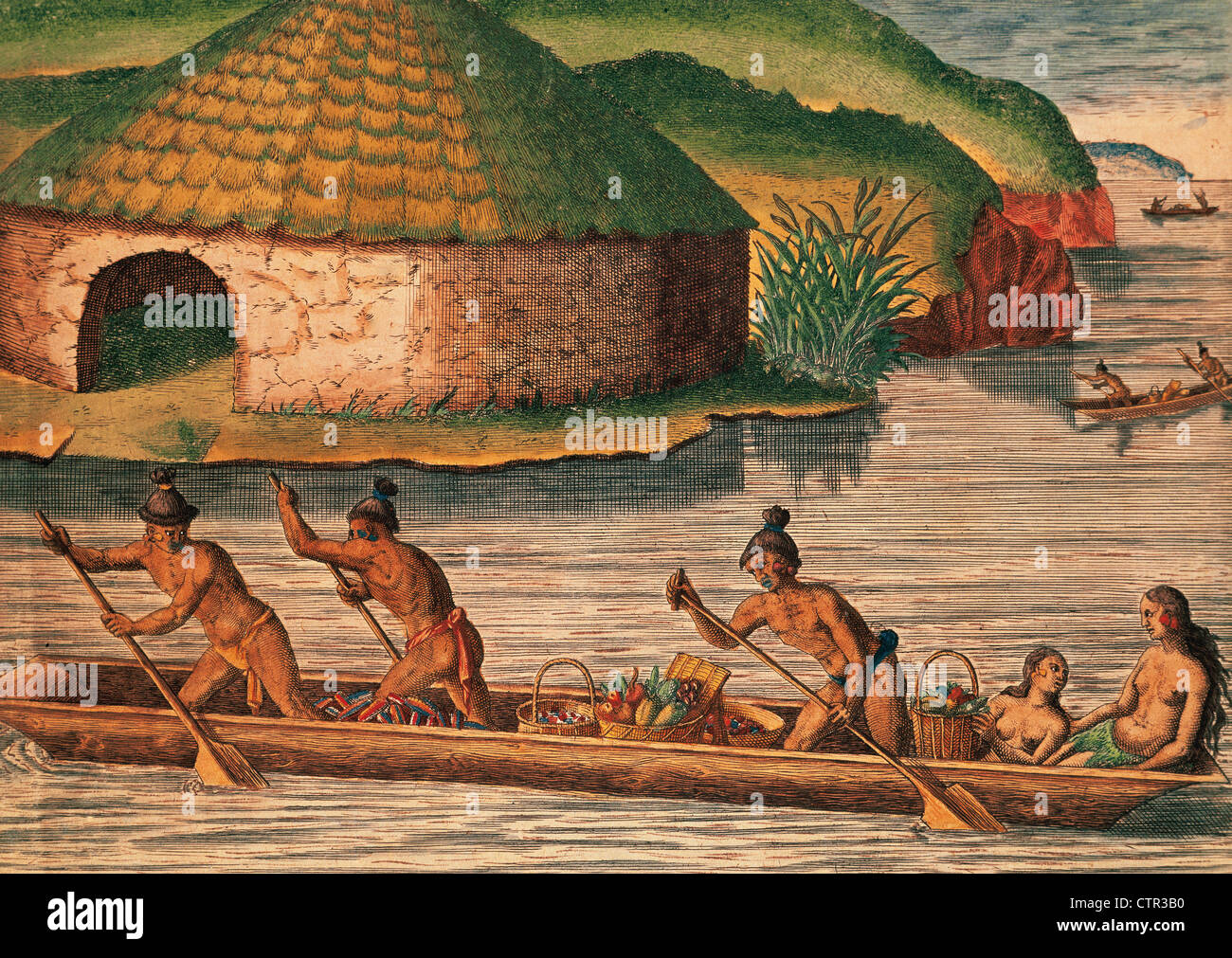

Their world was one of abundant resources. The Timucua were expert hunter-gatherers, skillfully exploiting the rich biodiversity of their environment. They fished the bountiful rivers and coastal waters, hunted deer, bear, and smaller game in the forests, and gathered nuts, berries, and wild plants. Crucially, they were also accomplished agriculturalists, cultivating maize (corn), beans, squash, and other crops, which formed the cornerstone of their diet and allowed for the development of stable, sedentary villages. These villages, often circular with a central plaza, were home to large, communal structures and individual family dwellings, typically constructed from wood and thatch.

Archaeological evidence paints a picture of a sophisticated society. The Timucua crafted intricate pottery, tools from stone and bone, and baskets from natural fibers. They were known for their distinctive tattooing and body painting, which served as markers of status, achievement, and group identity. Spiritual beliefs revolved around a reverence for nature, ancestral spirits, and powerful deities, often expressed through elaborate burial practices and the construction of ceremonial mounds. These mounds, some of which still stand today, served as burial sites, platforms for chiefs’ homes, or locations for religious rituals, reflecting a deep connection to the land and the cosmos.

The French and Spanish Crucible: First Encounters

The tranquility of the Timucua world was shattered in the mid-16th century with the arrival of European explorers and colonists. The first significant encounters were with the French Huguenots, led by Jean Ribault and René de Laudonnière, who established Fort Caroline near present-day Jacksonville in 1564. Laudonnière’s journals provide some of the earliest and most detailed, albeit biased, descriptions of Timucua life, noting their impressive physical stature, their complex political organization, and their initial curiosity and willingness to trade. The French sought alliances with various Timucua chiefdoms, particularly the Saturiwa, in their efforts to establish a foothold in the New World and challenge Spanish dominance.

However, the French presence was short-lived. In 1565, the Spanish, under the formidable leadership of Pedro Menéndez de Avilés, arrived and established St. Augustine, the oldest continuously inhabited European-established settlement in the United States. Menéndez, driven by a desire to protect Spain’s claims and eradicate the Protestant French, swiftly attacked Fort Caroline, massacring most of its inhabitants. This pivotal event marked the beginning of a prolonged and ultimately devastating Spanish influence on the Timucua.

Initially, the Spanish, like the French, sought alliances with various chiefdoms to secure their territorial claims and control trade routes. But their primary long-term goal was the spiritual conquest and conversion of the indigenous population to Catholicism. This ushered in the era of the Spanish mission system.

The Mission System: A Path to Erasure

Beginning in the late 16th century, Franciscan friars embarked on an ambitious program to establish missions throughout Timucua territory. These missions, often built near existing Timucua villages, were intended to be centers of religious instruction, cultural assimilation, and Spanish control. Timucua people were encouraged, and often compelled, to convert, adopt European customs, and participate in Spanish labor systems.

The mission system was a double-edged sword. On one hand, it provided a degree of protection for some Timucua groups against hostile chiefdoms or other European powers. It also introduced new technologies, crops, and livestock. On the other hand, it fundamentally undermined Timucua culture and autonomy. Traditional spiritual practices were suppressed, leaders’ authority diminished, and the Timucua were forced to labor for the Spanish, building churches, cultivating fields, and transporting goods. This forced labor, coupled with the disruption of traditional subsistence patterns, led to increased hardship and resentment.

Crucially, the missions became vectors for disease. The Timucua, like other indigenous peoples of the Americas, had no natural immunity to Eurasian diseases such as smallpox, measles, influenza, and bubonic plague. These diseases, inadvertently carried by the Europeans, swept through the densely populated mission villages with horrifying speed and lethality.

The Great Cataclysm: Disease, War, and Enslavement

The true catastrophe for the Timucua was not primarily military defeat, but epidemiological devastation. Historians estimate that the pre-contact Timucua population may have been as high as 200,000 people. By the early 17th century, epidemics had already reduced their numbers dramatically. The most devastating outbreaks occurred in 1613-1617 and again in 1649-1650, wiping out entire villages and chiefdoms.

"The impact of European diseases on the Timucua was nothing short of apocalyptic," notes historian Dr. Kathleen Deagan. "They faced wave after wave of pathogens for which they had no defense, leading to a population collapse that fundamentally destabilized their societies and made them highly vulnerable."

Compounding the disease crisis was the relentless pressure of colonial warfare. As the English established colonies in Carolina to the north, they began to raid Spanish Florida, often allying with other Native American groups, most notably the Creek (Muscogee) Confederacy. These raids, particularly intense in the late 17th and early 18th centuries, targeted the Spanish missions and their Timucua inhabitants. The primary objective was often to capture Timucua people for enslavement, either to be sold in the Carolina slave markets or to work on plantations.

The English and Creek raids were brutal and highly effective. They systematically destroyed mission villages, killed those who resisted, and enslaved thousands. The remaining Timucua, already weakened by disease and cultural disruption, were caught between competing colonial powers and hostile indigenous groups. Many fled, seeking refuge closer to St. Augustine, or attempting to integrate with other surviving tribes.

By the early 18th century, the once-mighty Timucua population had dwindled to a mere few hundred individuals. The last known remnants were a small group residing near St. Augustine and eventually evacuated to Cuba when Florida passed to British control in 1763. As a distinct tribal entity, the Timucua were, tragically, considered extinct.

The Enduring Legacy: Archaeology and Remembrance

Despite their disappearance as a unified people, the Timucua have left an indelible mark on Florida’s history and landscape. Their legacy is primarily preserved through the diligent work of archaeologists and historians who continue to unearth the fragments of their vibrant past.

Archaeological sites across northern Florida provide crucial insights into Timucua life. Sites like Mill Cove Complex, Fort Caroline National Memorial, and the San Luis de Talimali site (a reconstructed mission near Tallahassee) offer tangible connections to their villages, their pottery, their tools, and their spiritual practices. These sites are windows into a pre-Columbian world, allowing researchers to reconstruct daily life, political structures, and the profound changes brought by European contact.

The Timucuan language, though extinct, is known through a few surviving documents, including a catechism and some word lists compiled by Spanish missionaries. These linguistic fragments offer a glimpse into a unique language family, unrelated to most other Native American languages in the Southeast, underscoring the distinctiveness of Timucua culture.

Furthermore, Timucua influence subtly persists in the modern landscape through place names. While many indigenous names were lost or corrupted, some echoes remain. The Alachua region, for instance, derives its name from a Timucuan word for "sinkhole" or "big gulch," a testament to their deep knowledge and naming of the land.

Today, there is no federally recognized Timucua tribe. However, it is important to acknowledge that "extinction" in this context refers to the loss of a distinct cultural and political entity, not necessarily the complete eradication of their genetic lineage. It is highly probable that descendants of the Timucua survive today, integrated into other Native American communities (such as the Seminole or Creek nations) or the broader Florida population. Their heritage, though diffused, lives on in the bloodlines and collective memory of those who seek to understand Florida’s true origins.

The story of the Timucua is a powerful reminder of the profound human cost of colonization and the fragility of cultures in the face of overwhelming external forces. It is a narrative of a thriving civilization brought to its knees by disease, warfare, and cultural suppression. Yet, it is also a story of a people whose ingenuity, resilience, and deep connection to the land continue to resonate, urging us to remember the rich and complex tapestry of life that once flourished in the Palmetto State, long before its modern identity took shape. By unearthing their past, we not only honor the Timucua but also gain a deeper understanding of the enduring human spirit and the importance of preserving all cultures for future generations.