Echoes in the Valley: Fort Bosley and Pennsylvania’s Forgotten Frontier

Today, the Buffalo Valley in central Pennsylvania is a tableau of tranquil beauty. Rolling farmlands stretch beneath an expansive sky, punctuated by quiet towns and the meandering Buffalo Creek. It’s a landscape that whispers of peace, of generations tending the soil. Yet, beneath this placid surface lies a deeper history, one etched in fear, courage, and the relentless struggle for survival on the American frontier. Here, in the mid-18th century, stood Fort Bosley, not a grand military bastion, but a humble, vital bulwark against a relentless tide of violence – a testament to the resilience of ordinary settlers caught in the crucible of colonial conflict.

To understand Fort Bosley is to understand the terrifying realities of Pennsylvania’s western frontier during the French and Indian War (1754-1763) and subsequent conflicts like Pontiac’s War. Pennsylvania, founded on Quaker ideals of peace and fair dealings with Native Americans, found itself ill-prepared for the brutal realities of imperial expansion and land hunger. As European settlers pushed westward, encroaching on ancestral hunting grounds, tensions with the Lenape (Delaware) and Shawnee nations, often allied with the French, escalated. The colony’s pacifist government initially resisted building a defensive military infrastructure, leaving its exposed frontier settlements dangerously vulnerable.

The catalyst for the construction of many such forts, including Bosley, was a single, horrific event that shattered Pennsylvania’s illusion of peace: the Penn’s Creek Massacre. On October 16, 1755, a raiding party of Lenape and Shawnee warriors, incensed by years of land dispossession and broken treaties, attacked settlements along Penn’s Creek in what is now Snyder County. Approximately 25 settlers were killed, and more than 15, primarily women and children, were taken captive. The brutality of the attack, particularly the abduction of women and children, sent shockwaves through the colony.

Conrad Weiser, a prominent interpreter and colonial official, described the panicked aftermath in a letter to Governor Robert Hunter Morris: "The people are in a great consternation, and are moving their families and effects down to the interior parts of the province. They cry aloud for protection, and if they have none, they will be obliged to leave the country." This massacre, occurring less than two months after General Braddock’s disastrous defeat in western Pennsylvania, ignited a desperate scramble for defense. The Quaker-dominated Assembly, finally yielding to public outcry and the stark reality of war, authorized the construction of a chain of frontier forts.

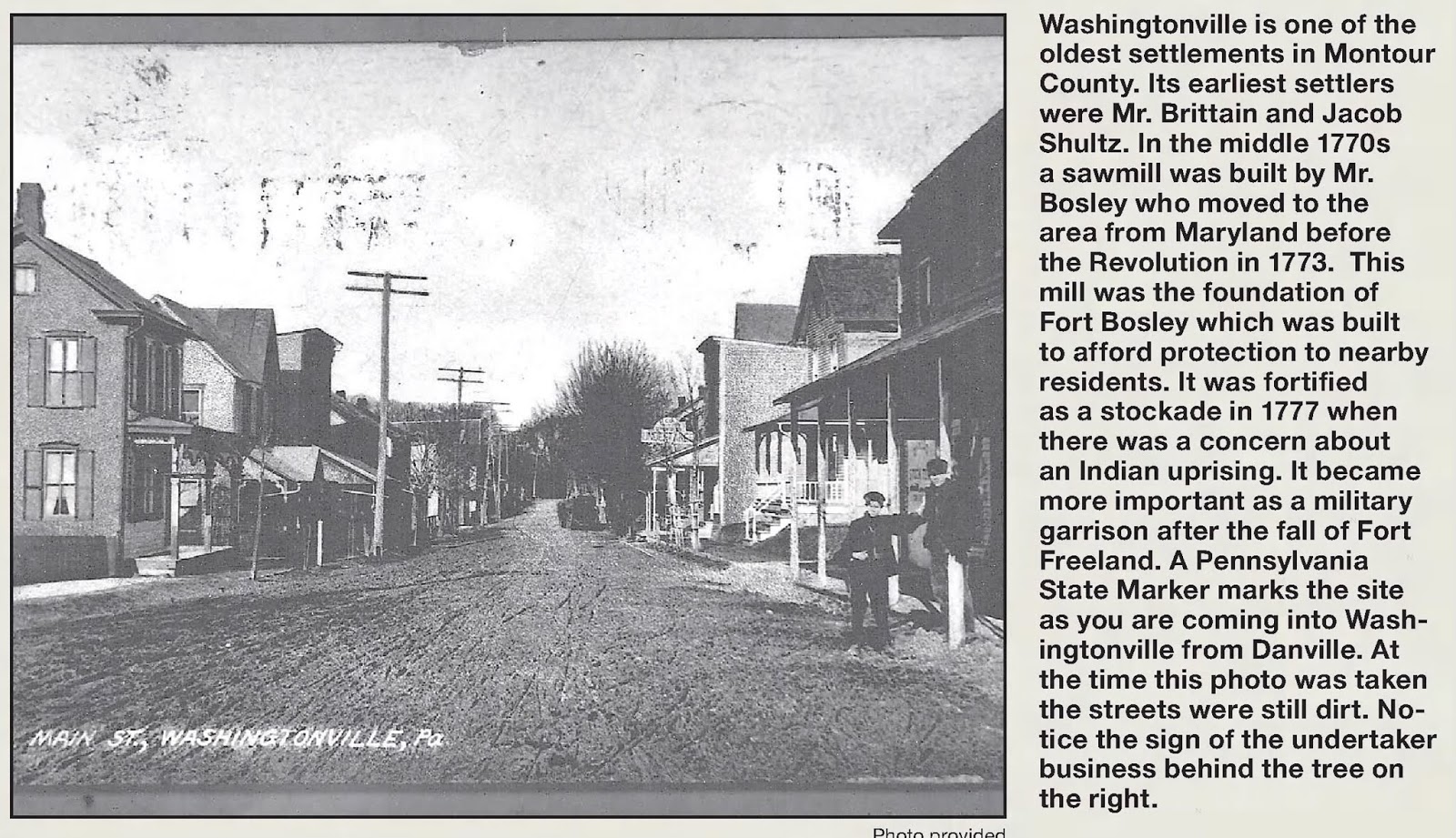

Fort Bosley was not a government-built fort in the same vein as Fort Augusta or Fort Lyttelton. Instead, like many smaller frontier strongholds, it likely began as a fortified farmstead, a private initiative born of communal necessity and self-preservation. It was situated on the property of Thomas Bosley, a settler in the Buffalo Valley, near the confluence of Buffalo Creek and the Susquehanna River. Its strategic location offered some protection to the scattered homesteads in the fertile valley, providing a refuge for families and their livestock during times of alarm.

These "forts" were typically less sophisticated than their military counterparts. Often, they consisted of a large log house or blockhouse, surrounded by a palisade of sharpened logs driven vertically into the ground, forming a defensive enclosure. Inside, there would be space for several families, a well for water, and perhaps a small store of provisions and ammunition. Windows, if present, would be small and heavily shuttered, designed for observation and musket fire rather than light. Life within such a fort was one of constant vigilance, cramped conditions, and shared fear.

The men who garrisoned Fort Bosley were primarily local militia – farmers, hunters, and tradesmen who had taken up arms to protect their homes and families. They were not professional soldiers but citizen-soldiers, often poorly equipped, sporadically supplied, and always outnumbered. Their duty was to patrol the surrounding woods, scout for signs of hostile parties, and respond to alarms. The women and children, while seeking safety behind the palisades, were not idle; they cooked, mended, cared for the sick, and maintained the semblance of domestic life amidst the ever-present threat of attack.

The period following the Penn’s Creek Massacre saw the frontier erupt into a brutal war of attrition. Raids were frequent and unpredictable. Settlers venturing out to tend their fields or hunt for game risked ambush and capture. The psychological toll was immense. Imagine the constant tension: every rustle in the woods, every distant cry, every shadow could signal impending danger. Sleep was fitful, punctuated by the imagined sounds of war whoops or the very real cries of a sentry. The Buffalo Valley, like much of the frontier, became a zone of terror where daily survival was a precarious gamble.

Historical records, though sparse for many smaller forts like Bosley, offer glimpses into the daily struggles. Reports from provincial officers detail the pleas of settlers for more arms, ammunition, and men. They speak of the difficulty in maintaining garrisons, as men often had to return to their own farms to plant or harvest, leaving the forts undermanned. Disease was also a constant threat in the close quarters of a fort, often proving more deadly than enemy attacks.

Fort Bosley’s role was primarily defensive, a static point of refuge rather than an offensive launching pad. Its existence, however, was crucial in preventing the complete abandonment of the Buffalo Valley. The mere presence of such fortified positions, however humble, provided a degree of confidence for settlers to remain, to continue tilling the land, and to hold the line against encroachment. Without them, the frontier would have receded further east, ceding vast tracts of land to hostile forces.

As the French and Indian War drew to a close with British victory in 1763, a brief respite was hoped for. However, Pontiac’s War immediately flared up, as Native American nations, seeing their lands threatened by British expansion, launched a coordinated uprising. The Pennsylvania frontier once again became a battleground, and forts like Bosley resumed their vital function. Attacks on isolated farms continued, and the cycle of fear and defense persisted.

Over time, as the frontier moved westward and treaties were eventually negotiated (albeit often broken), the need for such forts diminished. Fort Bosley, like many others, likely faded from active military use, its palisades eventually decaying, its buildings returning to private use or falling into ruin. The exact date of its abandonment as a functional fort is unclear, but by the late 18th century, with the establishment of more permanent settlements and a more secure border, its military significance waned.

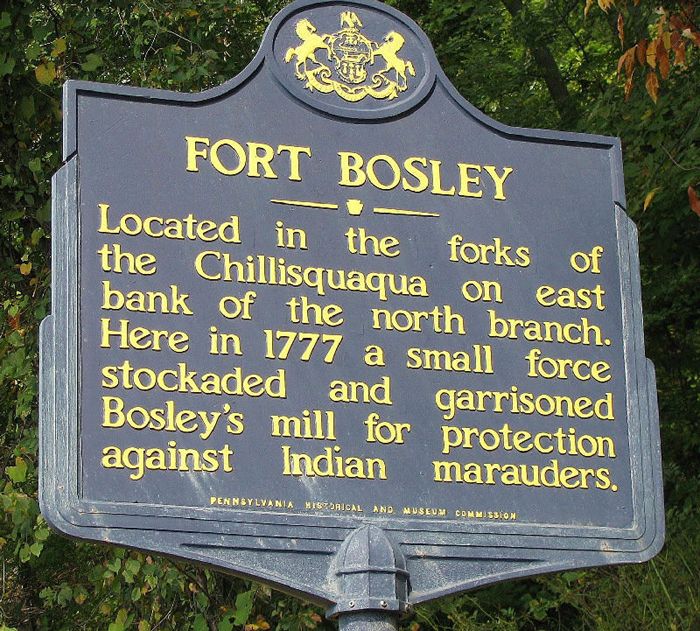

Today, little physical evidence remains of Fort Bosley. The land it once occupied has been farmed for centuries, its contours smoothed by time and agriculture. Its memory persists primarily in historical records, local histories, and the dedicated efforts of historians and archeologists who piece together the fragments of the past. A historical marker may stand as a silent sentinel, commemorating the bravery and sacrifice that once defined this peaceful valley.

Fort Bosley, though perhaps overshadowed by the grander narratives of colonial warfare, holds profound significance. It represents the unsung heroes of the frontier – the ordinary families who faced extraordinary dangers with resilience and courage. It reminds us that history is not just made in grand battles or by famous generals, but also in the quiet, desperate struggles of everyday people defending their homes and their hopes. The echoes of their vigilance, their fear, and their enduring spirit still resonate in the tranquil fields of the Buffalo Valley, a poignant reminder of Pennsylvania’s rugged and often brutal birth. It is a story not of triumph in conquest, but of survival against overwhelming odds, a testament to the enduring human will to carve out a life, even on the most dangerous of frontiers.