Echoes in the Valley: The Enduring Spirit of the Pennacook People

MERRIMACK VALLEY, NEW ENGLAND – Along the winding course of the Merrimack River, where the ancient forests meet the Atlantic’s salty breath, a story of profound resilience and enduring spirit unfolds. It is the story of the Pennacook people, an Algonquian-speaking confederacy whose ancestral lands once stretched across much of what is now New Hampshire, northeastern Massachusetts, and parts of southern Maine. Though often relegated to the footnotes of colonial history, their legacy is not one of disappearance, but of tenacious survival, adaptation, and an ongoing reclamation of identity against the tide of centuries.

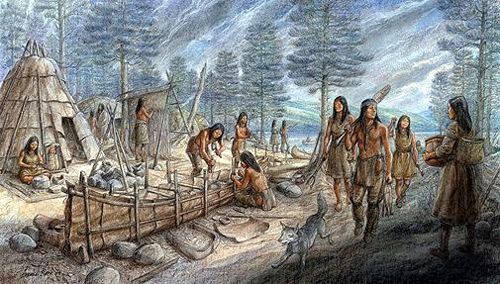

For millennia before European contact, the Pennacook thrived in this verdant landscape, their lives intricately woven into the rhythm of the seasons. Their name, often translated as "at the bend in the river" or "downhill place," reflects their deep connection to the Merrimack River, the lifeblood of their existence. This wasn’t merely a river; it was a highway, a pantry, and a spiritual conduit.

"Their existence was a masterclass in sustainable living," explains Dr. Margaret Newell, a historian specializing in early New England. "They practiced a sophisticated form of agriculture, cultivating corn, beans, and squash in fertile riverine plains, while also expertly managing the forests for hunting deer, moose, and bear. The Merrimack itself provided an abundance of salmon, alewives, and eels, caught with ingenious weirs and nets."

Their year was a cyclical migration. Spring brought them to the riverbanks for the vital fish runs. Summer saw them tending their crops in settled villages. Autumn was a time for harvesting and hunting in the uplands, gathering nuts and berries. Winters were spent in smaller, insulated family units, relying on stored provisions and the bounty of the deep woods. Their social structure was decentralized yet cohesive, led by sachems (chiefs) who governed through consensus and guided their people with wisdom and foresight. The Pennacook were also integral members of a broader network of Algonquian peoples, often associated with the Wabanaki Confederacy, sharing trade routes, cultural practices, and sometimes, military alliances.

The Dawn of a New World and Its Shadows

The arrival of European traders and settlers in the early 17th century irrevocably altered this ancient way of life. Initially, interactions were driven by trade – furs for European goods like metal tools, cloth, and firearms. But with the newcomers came devastating unseen forces: disease. Lacking immunity to European pathogens like smallpox, measles, and influenza, the Pennacook, like many Indigenous populations across the Americas, were decimated.

"The mortality rates were catastrophic," notes Dr. Newell. "Estimates suggest that between 75% and 90% of some Pennacook communities perished in the epidemics of the early 1600s, even before widespread English settlement. Entire villages were emptied. This wasn’t just a loss of life; it was a shattering of social structures, oral traditions, and the very fabric of their society."

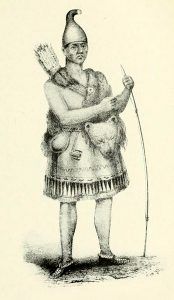

In the face of this existential threat, a powerful and sagacious leader emerged: Passaconaway, the Great Sachem of the Pennacook. Passaconaway, whose name means "Child of the Bear," was renowned not only for his political acumen and military prowess but also for his spiritual wisdom, rumored to possess shamanistic abilities. He understood the changing landscape and, recognizing the overwhelming numbers and advanced weaponry of the English, largely advocated for peace and diplomacy.

Historian Colin G. Calloway, in "The Western Abenakis of Vermont, 1600-1800," highlights Passaconaway’s difficult position: "He walked a tightrope, trying to preserve his people’s sovereignty and culture while navigating the relentless pressure of colonial expansion. His strategy was one of pragmatic accommodation, a stark contrast to the outright resistance many other leaders initially pursued."

Passaconaway famously delivered a farewell speech to his people around 1660, urging them to maintain peace with the English. While the exact words are debated, the sentiment attributed to him speaks volumes: "Hearken to me, my children, never contend with the English, nor make war with them… I am now an old man, and am going the way of all flesh. I would have you live in peace together." It was a plea born of profound experience and a grim understanding of the future.

The Unraveling: Wars and Dispossession

Despite Passaconaway’s efforts, the peace he sought proved fragile. As English settlements expanded, encroaching on Pennacook hunting grounds and prime agricultural lands, tensions escalated. The Pennacook found themselves caught in the brutal colonial wars that defined late 17th-century New England, particularly King Philip’s War (1675-1678).

Though many Pennacook initially attempted neutrality, they were often viewed with suspicion by the English. Incidents of betrayal and violence against Native communities, even those allied with the English or living in "Praying Towns" (settlements where Indigenous people converted to Christianity), forced many Pennacook into desperate alliances with other resisting tribes.

One particularly grim episode involved a Pennacook community led by Passaconaway’s son, Wonalancet. Despite their attempts at peace and neutrality, they were repeatedly subjected to raids and forced removals by colonial militias. Many were interned in harsh conditions, and some were even sold into slavery. The famous attack on the "Great Swamp" fort in Rhode Island, though targeting the Narragansett, sent a clear message of colonial brutality that resonated throughout the region.

The aftermath of King Philip’s War was devastating for the Pennacook. Their numbers further depleted by war, disease, and starvation, many were forced to abandon their ancestral lands. Some sought refuge with the Abenaki further north in what is now Vermont and Canada, others dispersed and assimilated into colonial society, sometimes hiding their Indigenous identity for safety.

"The myth of the ‘vanishing Indian’ was a convenient narrative for colonial powers," states Dr. Newell. "But the Pennacook didn’t simply vanish. They survived by adapting, by moving, by intermarrying, and by quietly maintaining their traditions out of sight of a hostile colonial gaze. Their history becomes less about a distinct, recognized tribe and more about the enduring presence of descendants and cultural memory."

The Quiet Persistence: Reclaiming Identity

For centuries, the story of the Pennacook was largely untold, or told only through the biased lens of colonial records. But in recent decades, a powerful movement has emerged among descendants to reclaim their heritage, revitalize their culture, and assert their enduring presence.

"Our ancestors were here, and we are still here," asserts a representative from a contemporary group identifying as Pennacook-Abenaki descendants, who prefers to remain anonymous due to ongoing efforts for broader recognition. "The land remembers us, and we remember the land. It’s in our blood, in our stories, in the very names of the rivers and mountains around us."

These modern efforts manifest in various ways:

- Genealogical Research: Descendants meticulously trace family lines, often connecting back to individuals recorded in colonial documents or through oral histories.

- Cultural Revitalization: Efforts are underway to relearn and teach the Algonquian language, revive traditional crafts, ceremonies, and storytelling.

- Land Stewardship: Many descendants are actively involved in environmental conservation, advocating for the protection of sacred sites and promoting sustainable practices that echo their ancestors’ deep respect for nature.

- Seeking Recognition: While federal recognition for Pennacook descendants remains a complex and challenging process, various groups are working towards state recognition and building community. This often involves collaborating with other Abenaki and Wabanaki communities.

One example of this ongoing presence is the Cowasuck Band of the Pennacook-Abenaki People, based in New Hampshire and Vermont, who trace their lineage to the Pennacook and other Abenaki communities. They actively engage in cultural education, land conservation, and community building, ensuring their heritage is not forgotten.

An Enduring Legacy

The Pennacook story is a poignant reminder of the profound human cost of colonization and the remarkable tenacity of Indigenous peoples. It challenges the simplistic narratives of conquest and disappearance, revealing instead a complex tapestry of adaptation, resistance, and quiet persistence.

The echoes of the Pennacook are still heard in the Merrimack Valley – in the names of its towns and rivers, in the ancient trails that crisscross its forests, and most importantly, in the hearts and minds of their descendants. Their journey from sovereign stewards of a vast homeland to a dispersed people fighting for recognition is a testament to the power of cultural memory and the enduring spirit of a people who, despite immense hardship, refuse to be erased from history.

As the sun sets over the Merrimack, casting long shadows across the land they once called home, the Pennacook story serves not just as a historical account, but as a living narrative of resilience, a call for justice, and a powerful testament to the unbreakable bond between people and their ancestral lands. Their past is a lesson, their present a struggle, and their future, a beacon of hope for cultural revitalization and recognition.