Echoes in the Wilderness: Unearthing the ‘More’ of Montana’s Frontier Forts

Montana. The very name conjures images of vast, untamed wilderness, soaring mountain ranges, and a history etched in the rugged spirit of the American West. For many, this history is encapsulated by iconic figures like Lewis and Clark, the gold rush prospectors, and the legendary conflicts with Native American tribes. And central to this narrative are the forts – bastions of civilization, outposts of empire, and often, symbols of conquest. Fort Benton, the "River City," stands as a monumental testament to the fur trade and steamboat era, while Fort Shaw evokes images of the U.S. Army’s presence.

But to truly grasp Montana’s military and mercantile past, one must venture beyond these celebrated bastions and delve into the "more" – the scores of lesser-known, often ephemeral, and sometimes entirely forgotten forts, cantonments, and trading posts that dotted the landscape. These aren’t just ruins; they are textbooks etched into the very soil, offering a richer, more nuanced understanding of the complex forces that shaped the Treasure State.

The Great Artery and the Rush for Riches

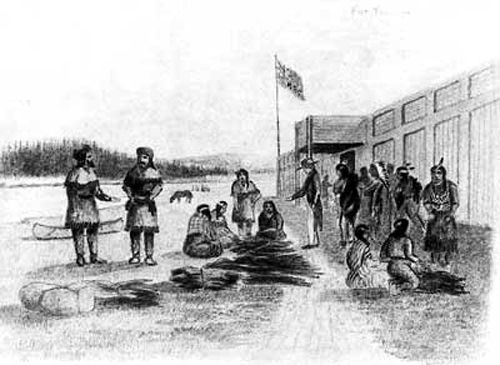

The story of Montana’s forts is inextricably linked to the Missouri River, often called the "Big Muddy." This winding waterway served as the primary highway into the interior of the continent for centuries, a lifeblood for indigenous peoples, and later, for European and American traders. Long before military garrisons, fur trading posts like those of the American Fur Company dotted the landscape, establishing a precarious peace and robust commerce with tribes like the Blackfeet, Crow, and Gros Ventre. These posts, often fortified with palisades and blockhouses, were the first "forts" in Montana, driven not by military strategy but by the insatiable demand for beaver pelts and buffalo hides in the burgeoning markets back East.

The mid-19th century saw Montana transform dramatically. The discovery of gold in places like Alder Gulch (Virginia City) and Last Chance Gulch (Helena) ignited a feverish rush, drawing thousands of prospectors, merchants, and opportunists to the remote territory. This sudden influx of population, coupled with growing tensions over land and resources with Native American tribes, necessitated a more formal military presence. The U.S. Army, tasked with protecting settlers, securing trade routes, and enforcing federal policies – often at the expense of indigenous sovereignty – began establishing a network of military installations.

Beyond the Famous Palisade: The Unsung Outposts

While Fort Benton commanded the river traffic and Fort Shaw secured a vast agricultural region, many other forts played crucial, albeit less glamorous, roles. These were the workhorses of the frontier, often built quickly, manned by small garrisons, and sometimes abandoned just as fast when their strategic purpose waned.

Consider Fort Ellis, established in 1867 near present-day Bozeman. While perhaps not as famous as Benton, Fort Ellis was strategically vital. It protected the Bozeman Trail, a shortcut to the Montana goldfields that cut directly through prime hunting grounds of the Lakota Sioux, Northern Cheyenne, and Arapaho. It also served as a base of operations against hostile Native American bands and offered protection to the nascent agricultural communities in the Gallatin Valley. Its soldiers endured harsh winters, isolation, and the constant threat of attack, embodying the difficult life of a frontier trooper.

Further north, near present-day Chinook, lay Fort Assinniboine. Established in 1879, it was one of the largest and most significant military posts in Montana during the late 19th century, designed to monitor the border with Canada and control the movements of Native American tribes, particularly the Métis and Nez Perce, who often sought refuge across the border. Fort Assinniboine was a formidable installation, boasting extensive facilities, a substantial garrison, and even its own telegraph line. Its sheer scale and prolonged existence speak volumes about the U.S. government’s determination to assert control over the northern plains in the post-Civil War era.

Then there are forts like Fort Custer, established in 1877 at the confluence of the Bighorn and Little Bighorn rivers, a mere year after the infamous Battle of the Little Bighorn. This fort was a direct response to the need for a strong military presence in the heart of Crow and Sioux territory, intended to prevent further conflict and enforce treaty obligations. Its location, rich with historical resonance, underscores the turbulent nature of the frontier.

And what about Fort Logan? Located in central Montana, south of Great Falls, it was established in 1869 to protect the stagecoach route between Helena and Camp Cooke. While smaller and less prominent than some of its counterparts, Fort Logan served a critical function, providing a secure stopping point and a visible military presence in a vast and often dangerous landscape. Its story highlights the intricate network of protection the Army attempted to weave across the territory.

"These aren’t just dots on a map; they are complex ecosystems of human endeavor, conflict, and survival," explains Dr. Evelyn Reed, a historian specializing in the American West. "Every stone, every depression in the earth, tells a story of ambition, hardship, and the clash of cultures. The ‘more’ of Montana’s forts isn’t just about uncovering new sites; it’s about re-evaluating their collective significance."

Life Within the Walls: A Microcosm of the Frontier

Life within these fortified walls was a curious blend of tedium and terror. Soldiers, often young men from diverse backgrounds, faced grueling drills, strict discipline, and the ever-present threat of boredom, disease, and Native American raids. Winters were brutally cold, summers sweltering, and the isolation profound. Supplies were often scarce, and communication with the outside world could take weeks or months.

A fictionalized, but representative, entry from a soldier’s diary at Fort Ellis might read: "October 14, 1871. Another week of drilling, the dust a constant companion. Sergeant O’Malley is on one of his moods. The wind howls tonight, a lonely sound. Heard tell of a small raiding party near the Musselshell; prayers for the families there. Mail’s late again. A man could go mad out here if he let himself."

Yet, these forts were also burgeoning communities. Officers often brought their families, creating a semblance of domesticity in the wilderness. Laundresses, cooks, blacksmiths, and traders formed a civilian support system. Native American scouts and interpreters played crucial roles, often acting as intermediaries and intelligence gatherers, navigating the complex cultural divides. These interactions, sometimes cooperative, sometimes confrontational, further enriched the tapestry of frontier life.

The Ephemeral and the Unseen

Even more fleeting were the numerous temporary camps and cantonments established during specific campaigns or for short-term strategic needs. These might have been little more than a collection of tents, wagons, and hastily dug rifle pits, but their impact was real. They represented the mobile arm of the military, pushing deeper into contested territories, often marking the initial points of contact and conflict. Identifying and understanding these ephemeral sites is a significant challenge for archaeologists, but their existence adds another layer to the "more" of Montana’s forts.

Furthermore, it’s imperative to remember that these forts represent one side of a complex narrative. While American military forts were being constructed, Native American tribes also had their own "fortifications" – strategically chosen defensive positions, fortified camps, and natural strongholds that served to protect their communities and resources. These indigenous defensive structures, often temporary and utilizing the natural landscape, are rarely given the same prominence in historical accounts but are equally vital to understanding the era’s conflicts.

The Enduring Legacy: From Ruins to Revelation

Today, many of these "more" forts exist as little more than faint depressions in the earth, crumbling foundations, or reconstructed interpretive centers. Some have been swallowed by private land, others protected as state parks or historical sites. But their stories resonate still.

Archaeologists continue to uncover artifacts – uniform buttons, spent cartridges, broken pottery, trade beads – that paint vivid pictures of daily life and momentous events. "Our work peels back layers of time, revealing not just military history, but the broader human story of adaptation, resilience, and often, profound cultural misunderstanding," says Dr. Aaron Peterson, an archaeologist involved in several Montana fort excavations. "The smallest artifact can unlock a huge narrative."

Historical societies, local communities, and tribal nations are increasingly engaged in preserving and interpreting these sites. They serve as powerful educational tools, allowing visitors to connect with a tangible past, to grapple with the complexities of westward expansion, and to understand the profound impact these outposts had on both settlers and indigenous peoples.

The ‘more’ of Montana’s forts isn’t just about finding new locations; it’s about finding new layers of meaning in familiar landscapes. It’s about recognizing the vast network of human activity that defined the frontier, acknowledging the diverse perspectives of those who lived and died there, and understanding that history is rarely as simple as a single, well-known landmark. These forgotten bastions and ephemeral outposts are not silent; they are whispering tales of a rugged past, inviting us to listen more closely and learn more deeply from the enduring echoes in the wilderness. They remind us that the story of Montana, like its expansive horizons, is far richer and more intricate than meets the eye.