Echoes of Betrayal: The Cheyenne War of 1864-65 in Nebraska

The year 1864 dawned with an unsettling quiet across the vast, undulating plains of Nebraska, a quiet that belied the simmering tensions beneath its surface. The Platte River Road, a vital artery of westward expansion, pulsed with the relentless march of emigrants, prospectors, and supply wagons. To the north and south, the buffalo herds, once boundless, were visibly dwindling, and with them, the traditional way of life for the Cheyenne, Lakota, and Arapaho peoples who had called these lands home for centuries. This uneasy coexistence was a fragile veneer, stretched thin by broken treaties, land encroachment, and a pervasive sense of mistrust. By year’s end, the quiet would shatter into a bloody symphony of violence, culminating in a bitter, retaliatory war that scorched the Nebraska Territory and left an indelible scar on the American frontier.

The stage for this conflict was set by the relentless tide of Manifest Destiny. The discovery of gold in Colorado in 1858-59 triggered a massive influx of white settlers, directly through the heart of Native American hunting grounds. The Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851, which had ostensibly guaranteed vast territories to various tribes, was increasingly disregarded. Subsequent treaties, often negotiated under duress with unrepresentative tribal leaders, further whittled away Native lands, confining the Cheyenne and Arapaho to a fraction of their ancestral domains in southeastern Colorado and southwestern Kansas, bordering Nebraska.

Adding to the complexity was the American Civil War, which had drained federal troops from the Western frontier. Their place was often taken by inexperienced, ill-disciplined, and frequently hostile volunteer regiments, particularly the Colorado Volunteers. These units, fueled by a mixture of patriotic fervor, land hunger, and outright racism, viewed the Native Americans not as sovereign nations, but as obstacles to be removed. Colorado’s territorial governor, John Evans, and Colonel John M. Chivington, a former Methodist preacher turned military officer, epitomized this aggressive stance, openly advocating for a war of extermination against any Indians who resisted American expansion.

The Tinderbox Ignites: Summer 1864 Raids

The fragile peace began to unravel in the spring and summer of 1864. Reports of scattered raids on isolated ranches, stagecoach stations, and emigrant trains along the Platte River Road became more frequent. These incidents, often fueled by desperation born of starvation and a sense of betrayal, were sometimes in retaliation for previous aggressions by white settlers or soldiers. A critical flashpoint occurred in August 1864 along the Little Blue River in south-central Nebraska, where a series of raids by Cheyenne and Lakota warriors, often attributed to the Dog Soldiers – a militant Cheyenne warrior society – resulted in several deaths and the capture of women and children. This, along with the Plum Creek Massacre further west along the Platte, near present-day Lexington, Nebraska, where a freight train was attacked, brought the conflict directly to Nebraska’s doorstep and sent shockwaves across the frontier.

The immediate military response was often chaotic and ineffective, with volunteer units struggling to locate and engage the highly mobile warriors. Governor Evans issued a proclamation in August, urging "friendly Indians" to report to designated forts for protection, while effectively declaring open season on any who did not. This ultimatum, however, was often misinterpreted or never reached many bands, further escalating tensions.

Sand Creek: The Catalyst for War

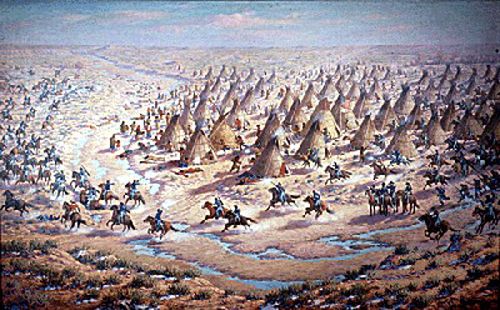

But the true inferno that ignited the Plains, transforming isolated skirmishes into a full-blown war that swept through Nebraska, was not in Nebraska at all. It was the horrific Sand Creek Massacre, which occurred on November 29, 1864, in southeastern Colorado. Colonel Chivington, leading a force of some 700 Colorado Volunteers, attacked a peaceful encampment of Cheyenne and Arapaho under Chief Black Kettle. Black Kettle, having been assured of safety and flying both an American flag and a white flag of truce, believed his people were under military protection.

What followed was an act of unspeakable brutality. Despite the peace flags, Chivington ordered his men to attack, famously declaring, "Kill and scalp all, big and little." The soldiers slaughtered over 150 Native Americans, mostly women, children, and the elderly. The atrocities committed – mutilation of bodies, scalpings, and other horrors – were so egregious that they later prompted a Congressional investigation and widespread condemnation.

Sand Creek was not merely a battle; it was a profound act of betrayal that shattered any lingering hope of peaceful coexistence. For the Cheyenne, Lakota, and Arapaho, it was a declaration of total war. The massacre transformed the character of the conflict from scattered raids to a unified, retaliatory campaign. Warriors who had previously considered peace now vowed vengeance. As George Bent, a mixed-blood Cheyenne who participated in the subsequent war, recounted, "The Sand Creek affair was the starting of all the trouble with the Cheyennes and Arapahos, and Sioux."

The Nebraska Winter War of Retaliation (1864-1865)

Fueled by grief and an unquenchable thirst for vengeance, the surviving Cheyenne and Arapaho, joined by their Lakota allies, especially the Oglala and Brulé Sioux, moved north, converging in the Republican and Smoky Hill River valleys, close to the Nebraska border. Their immediate target: the white settlements and military outposts that lined the Platte River Road, particularly in Nebraska.

The bitter winter of 1864-65 offered little respite. The unified tribes, numbering an estimated 1,000 to 1,500 warriors, began a systematic campaign of destruction. Their objective was clear: to cleanse their lands of the white invaders and punish them for the atrocities of Sand Creek. They attacked ranches, burned stagecoach stations, cut telegraph lines, and ambushed wagon trains. The Platte River Road, the lifeblood of westward travel, effectively ground to a halt.

The most prominent event of this winter war in Nebraska was the Julesburg Raid (often called the First Battle of Julesburg). On January 7, 1865, a massive force of Cheyenne, Lakota, and Arapaho warriors descended upon Julesburg, a vital stagecoach station, telegraph office, and military post (Fort Rankin) in the extreme western Nebraska Territory. The warriors, some of whom carried scalps and other gruesome trophies from Sand Creek, feigned an attack on the fort to draw out its small garrison of soldiers, mostly Company F of the 1st Nebraska Cavalry. The soldiers, under Lieutenant William H. Lowman, fell into the trap, were ambushed, and suffered heavy casualties. The warriors then turned their attention to the Julesburg station, looting and burning it.

A fascinating detail from this engagement, recounted by George Bent, involved the warriors’ discovery of a stash of whiskey. The subsequent revelry, however, allowed the remaining soldiers to regroup within the fort. After their initial success, the warriors withdrew, laden with supplies and horses, but the incident sent a clear message: the Plains tribes were a formidable, unified force, and they were striking back with unprecedented ferocity.

Following the Julesburg raid, the tribes continued their rampage. For weeks, they virtually controlled the Platte River Valley in Nebraska, conducting numerous smaller raids, destroying property, and disrupting communication and travel. They attacked the Godfrey Ranch, the Mud Springs station, and other key points along the emigrant trail. The sheer scale and coordinated nature of these attacks demonstrated a strategic unity rarely seen before, born directly from the trauma of Sand Creek.

The U.S. military response was slow and largely ineffective. Major General Samuel R. Curtis, commander of the Department of Kansas, launched a punitive expedition in late January 1865. His troops, facing brutal winter conditions and the challenge of tracking a highly mobile enemy across vast, snow-covered plains, struggled to engage the warriors. The Native American strategy of hit-and-run, coupled with their superior knowledge of the terrain and the severe weather, largely frustrated the American efforts.

The Exodus and Lasting Legacy

By late February and early March 1865, having inflicted significant damage and taken their revenge, the allied tribes began to move north, crossing the Platte and heading towards the Powder River country in present-day Wyoming and Montana. This northward migration was partly to escape the relentless pursuit of the U.S. Army and partly to seek new hunting grounds, as the buffalo in Nebraska were becoming scarce. This movement effectively brought an end to the immediate phase of the Cheyenne War in Nebraska, but it merely shifted the conflict to new territories, setting the stage for future clashes like Red Cloud’s War.

The Cheyenne War of 1864-65 in Nebraska, inextricably linked to the horror of Sand Creek, stands as a stark testament to the tragic consequences of westward expansion, cultural clash, and broken trust. It was a war of retribution, ignited by an act of barbarism and fought with a ferocity born of desperation and deep-seated grievance.

For the emigrants and settlers in Nebraska, the winter of 1864-65 was a period of terror and economic paralysis. The Platte River Road, once a symbol of progress, became a gauntlet of danger. For the U.S. Army, it exposed the limitations of conventional warfare against a determined and mobile indigenous enemy.

But for the Cheyenne, Lakota, and Arapaho, it was a tragic, if defiant, chapter in their struggle for survival. While they inflicted heavy damage and achieved a measure of revenge, the long-term trajectory remained unchanged. The war further solidified the American resolve to "pacify" the Plains, leading to more campaigns, more treaties, and ultimately, the further displacement and subjugation of Native peoples. The echoes of betrayal from Sand Creek continued to reverberate across the plains, shaping the brutal narrative of the Indian Wars for decades to come, a somber reminder of a nation’s expansion built on conflict and profound injustice.