Echoes of Cedar and Salmon: The Enduring Spirit of the Salishan Peoples

From the sun-drenched beaches of the Pacific to the rugged peaks of the Rockies, a rich tapestry of Indigenous cultures has thrived for millennia, intricately woven into the very fabric of the land. Among the most widespread and diverse of these are the Salishan peoples, a vast linguistic and cultural family whose ancestral territories span British Columbia, Washington, Oregon, Idaho, and Montana. Their story is one of profound connection to place, sophisticated societal structures, immense resilience in the face of colonial upheaval, and a powerful resurgence of identity in the modern era.

The term "Salishan" refers primarily to a family of over 20 distinct languages, spoken by numerous individual nations or tribes, each with its own unique customs, governance, and history. These groups are broadly categorized into Coast Salish, inhabiting the coastal regions and islands, and Interior Salish, found in the inland plateaus and mountains. Despite their geographic separation, they share deep linguistic roots and a common worldview centered on reciprocity, respect for the natural world, and a profound sense of community.

A Millennia of Sophistication: Pre-Contact Life

Before the arrival of European explorers and settlers, Salishan societies were complex and highly organized. Their economies were based on a sustainable relationship with their environment, characterized by seasonal rounds of hunting, fishing, and gathering. Salmon, in particular, was the lifeblood of many communities, celebrated in ceremonies and meticulously managed to ensure its perpetual return. "Salmon is more than just food; it is our relative, our teacher, our way of life," explains Elder Robert Charles of the Lummi Nation, a sentiment echoed across Salishan territories. "It teaches us about cycles, about giving back, about abundance."

Coastal Salish peoples were renowned for their sophisticated cedar culture. The mighty cedar tree provided everything from vast longhouses – some accommodating hundreds of people – to intricately carved canoes capable of navigating the treacherous Pacific waters, clothing, tools, and ceremonial regalia. Their artistic traditions, particularly in weaving and carving, were highly developed, reflecting a deep spiritual connection to their surroundings. Social structures were often hierarchical, with inherited leadership and a strong emphasis on community welfare. Potlatches, elaborate gift-giving ceremonies, were central to social and political life, used to mark important events, distribute wealth, and affirm status.

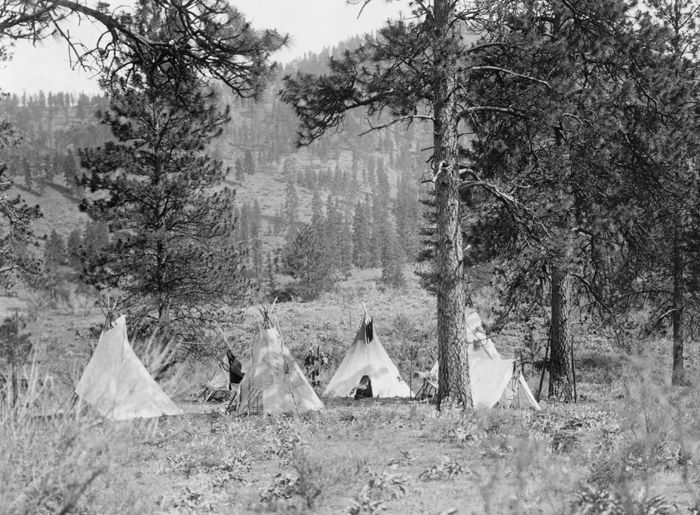

Inland Salish groups, such as the Flathead (Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes), Spokane, and Coeur d’Alene, adapted to their diverse interior environments, relying on bison hunting, camas root gathering, and fishing in rivers and lakes. Their horsemanship skills, acquired after the introduction of horses by Europeans, transformed their mobility and hunting practices, enabling them to travel great distances across the plains. Despite these regional variations, a shared philosophy of living in harmony with the land and all its creatures underpinned their existence.

The Great Disruption: Contact and Colonialism

The arrival of Europeans brought catastrophic changes to Salishan communities. Beginning in the late 18th century, diseases like smallpox, measles, and influenza, to which Indigenous peoples had no immunity, swept through communities, often wiping out up to 90% of the population. This demographic collapse decimated generations of knowledge keepers, spiritual leaders, and skilled artisans, leaving survivors reeling.

Following the initial devastation, the 19th and 20th centuries saw waves of aggressive colonization. Treaties, often poorly understood or outright broken by colonial governments, led to the loss of vast ancestral lands, forcing Salishan peoples onto small, confined reservations. The influx of settlers brought resource extraction industries like logging and fishing, which often disregarded traditional management practices and further degraded the environment.

Perhaps the most insidious assault on Salishan cultures came through policies of forced assimilation. In Canada, the Potlatch Ban, enacted in 1884 and lasting until 1951, criminalized central cultural practices, including ceremonies, dances, and language use. Simultaneously, both in Canada and the United States, Indigenous children were forcibly removed from their families and sent to residential schools (known as Indian boarding schools in the U.S.). These institutions aimed to "kill the Indian in the child," stripping them of their language, culture, and identity, often through abuse, neglect, and trauma that continues to reverberate through generations. "My grandmother never spoke her language again after residential school," recounts Christine George, a Stó:lō Nation cultural worker. "She carried that pain, that silence, her whole life. We are still healing from that."

The Dawn of Reawakening: Resilience and Resurgence

Despite centuries of targeted oppression, the spirit of the Salishan peoples refused to be extinguished. In recent decades, a powerful movement of cultural revitalization, language reclamation, and the assertion of inherent sovereignty has gained momentum.

Language, recognized as the heart of cultural identity, is at the forefront of this resurgence. With many Salishan languages critically endangered, communities are dedicating immense resources to immersion programs, master-apprentice initiatives, and the development of educational materials. Elders, the last fluent speakers, are revered and tirelessly work to pass on their knowledge. The Squamish Nation, for example, has established a successful language immersion school, teaching Skwxwú7mesh sníchim to young children, while the Lummi Nation has developed a comprehensive online dictionary and learning tools for Xwlemi Chosen. These efforts are not merely about preserving words; they are about rekindling a worldview, reconnecting with ancestors, and restoring a unique way of understanding the world.

Cultural practices, once driven underground, are now openly celebrated. Potlatches and other traditional ceremonies are being revived, often adapted to contemporary contexts but retaining their core significance. Art forms like weaving, carving, and storytelling are experiencing a renaissance, with younger generations learning from elders and infusing traditional techniques with modern interpretations. These cultural expressions serve as powerful statements of identity and resilience.

Asserting Sovereignty and Stewardship

Beyond cultural revival, Salishan nations are actively asserting their inherent rights and responsibilities as sovereign peoples. This includes pursuing land claims, negotiating modern treaties, and engaging in self-governance. The Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes (CSKT) on the Flathead Reservation in Montana, for instance, have achieved significant strides in managing their natural resources, including water rights, and developing a robust tribal economy. Their proactive environmental stewardship often contrasts sharply with state and federal approaches, demonstrating a deep, ancestral understanding of ecological balance.

The fight for environmental justice and protection of sacred lands and waters is another crucial aspect of modern Salishan advocacy. From defending salmon runs against industrial pollution to opposing pipelines and resource extraction projects on ancestral territories, Salishan peoples are often at the forefront of environmental movements. They bring not only legal and scientific arguments but also a spiritual and cultural imperative to protect the natural world for future generations. "Our lands and waters are not just resources; they are living beings, our relatives," says Fawn Sharp, former President of the National Congress of American Indians and a member of the Quinault Indian Nation (Coast Salish). "When we protect them, we are protecting ourselves, our children, and our future."

Challenges and the Path Forward

Despite these triumphs, significant challenges persist. The legacy of colonialism continues to manifest in systemic issues such as poverty, inadequate healthcare, lower educational attainment, and disproportionate rates of incarceration within Indigenous communities. Climate change poses a direct threat to traditional food sources and ways of life, impacting salmon populations, cedar forests, and the availability of traditional medicines.

Yet, the Salishan peoples face these challenges with unwavering determination. Their strength lies in their profound connection to community, their reverence for elders, and their fierce hope for the future. Youth are increasingly engaged, learning their languages, participating in ceremonies, and advocating for their rights on global stages. They are bridging the wisdom of their ancestors with the tools of the modern world.

The story of the Salishan peoples is a vital narrative of endurance, adaptation, and an enduring spirit. It is a testament to the power of culture and language to survive and thrive against overwhelming odds. As the cedar stands tall, and the salmon tirelessly return upstream, so too do the Salishan peoples continue their journey, their voices echoing across their ancestral lands, reminding the world of their deep roots, their vibrant present, and their boundless future. Their story is not just a chapter in the history of North America; it is a living, breathing testament to human resilience and the unbreakable bond between people and place.