Echoes of Empire: The Tragic Saga of Fort Caroline

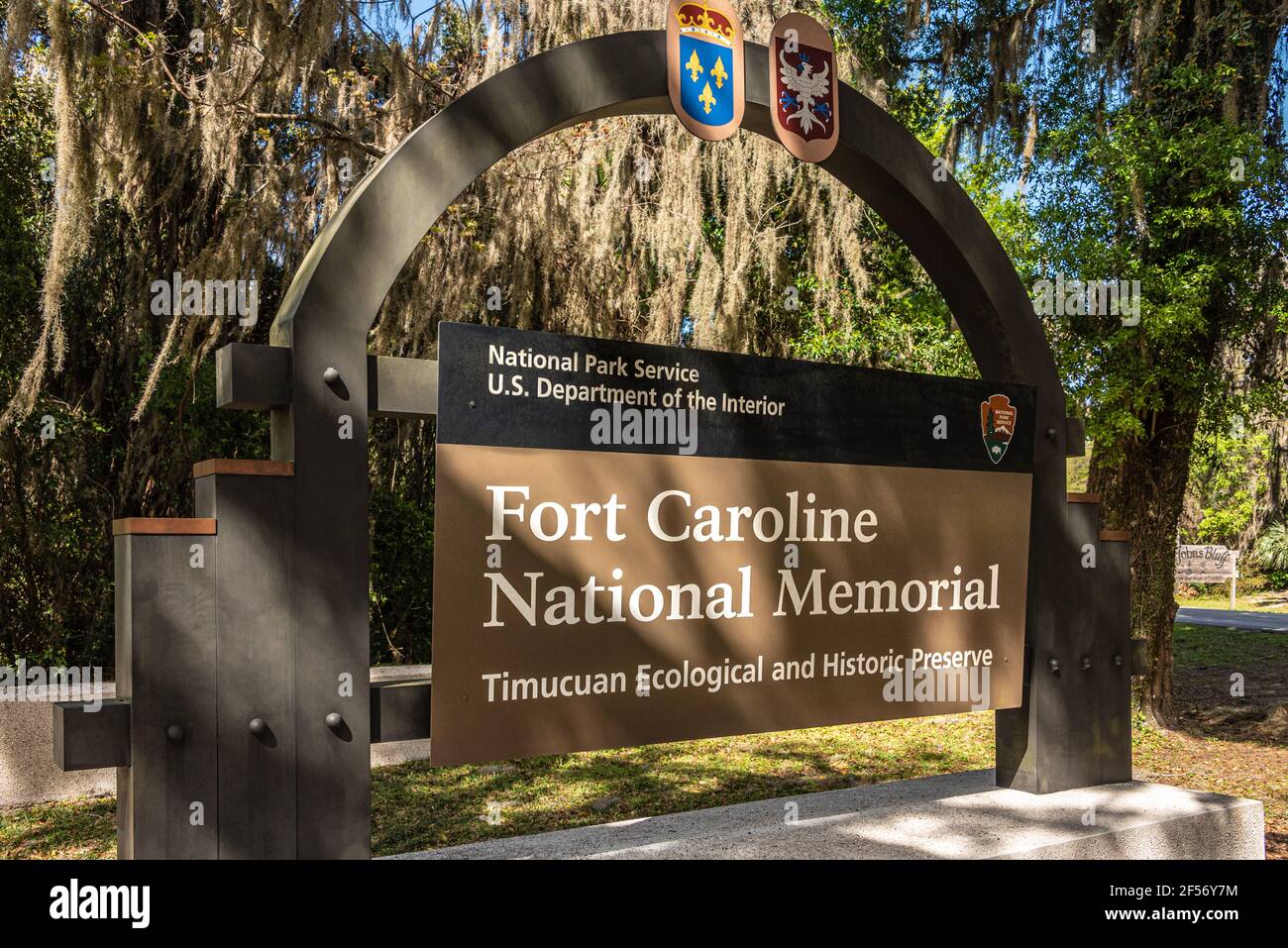

Nestled along the serene banks of the St. Johns River in modern-day Jacksonville, Florida, lies a testament to an ambition that burned bright and died in a blaze of religious fervor and imperial conflict: Fort Caroline. Today, the Fort Caroline National Memorial, part of the Timucuan Ecological and Historic Preserve, offers a tranquil setting for reflection. Yet, beneath the canopy of ancient oaks and beside the slow-moving river, whispers of a brutal past echo – a forgotten chapter that predates Jamestown and Plymouth, chronicling the first desperate European struggle for control of what would become the United States.

Fort Caroline’s brief, tumultuous existence from 1564 to 1565 represents a pivotal, bloody dawn of European colonialism in North America. It was a crucible where the competing ambitions of France and Spain, fueled by religious animosity and territorial claims, collided with devastating consequences for the early settlers and, inadvertently, for the indigenous Timucua people caught in the crossfire.

A French Dream of Refuge and Riches

The story of Fort Caroline begins in a fractured 16th-century France, torn by the Wars of Religion between Catholics and Huguenot Protestants. Admiral Gaspard de Coligny, a prominent Huguenot leader, harbored a grand vision: establish a French colony in the New World. This "Florida" colony would serve as a refuge for his persecuted co-religionists, a base for privateering against Spanish treasure fleets, and a strategic foothold to challenge Spain’s vast, if thinly settled, American empire.

In 1562, Jean Ribault, an experienced Huguenot navigator, led the first expedition. He explored the northeastern coast of Florida, discovering and naming the "River of May" (now the St. Johns River) due to his arrival in that month. He noted the fertile land and the friendly demeanor of the Timucua people, who greeted the French with curiosity and gifts. Ribault erected a stone column bearing the French coat of arms, claiming the territory for France, before returning home to secure more settlers and supplies. A small garrison of men was left at Port Royal (present-day South Carolina), but their isolated outpost quickly failed due to lack of supplies and discipline.

Two years later, in June 1564, a second French expedition, comprising three ships and around 300 colonists, arrived at the River of May. This time, the leader was René Goulaine de Laudonnière, Ribault’s former lieutenant. Guided by Ribault’s earlier reconnaissance, Laudonnière chose a bluff overlooking the river, about five miles inland from the Atlantic, to construct their settlement. They named it Fort Caroline, likely in honor of King Charles IX of France.

A Colony Beset by Hardship

The fort itself was a triangular palisade of logs and earth, with bastions at each corner. It was designed to offer defense, but its true challenge lay not in external threats initially, but in internal strife and the unforgiving wilderness. The colonists, a mix of soldiers, artisans, and gentlemen adventurers, were ill-suited for the rigors of colonial life. Many had come seeking instant riches, not the arduous labor required for farming or construction. Discipline quickly eroded.

Food supplies dwindled, exacerbated by poor planning and the fact that many Frenchmen were more interested in searching for gold than cultivating crops. Relations with the local Timucua, initially cordial, began to sour as the French, increasingly desperate, resorted to demanding food and labor. Laudonnière, though well-intentioned, struggled to maintain control. Mutinies erupted, with some colonists deserting to become pirates, raiding Spanish ships and even attacking Timucuan villages. Some of these renegades were captured by the Spanish and, under torture, revealed the existence and location of Fort Caroline – a fatal mistake.

"We had not much to hope for," Laudonnière wrote in his account, "but the succour and help of God." This sentiment reflected the precarious state of the colony. Disease was rampant, morale was low, and the dream of a French Florida seemed on the verge of collapse. It was a critical moment for the young colony, teetering on the brink of abandonment.

Spain’s Fury: A Challenge to Dominion

Meanwhile, news of the French presence infuriated the Spanish Crown. Spain considered all of La Florida – a vast, ill-defined territory encompassing much of the southeastern United States – as its exclusive domain, claimed by Ponce de León in 1513. The idea of Protestant "Lutheran pirates" establishing a base so close to the vital shipping lanes of the Bahama Channel, through which Spanish treasure fleets sailed from Mexico and Peru, was an intolerable affront to both their sovereignty and their Catholic faith.

King Philip II of Spain, a staunch defender of Catholicism, resolved to expel the French at all costs. He entrusted this crucial mission to Pedro Menéndez de Avilés, an Asturian admiral known for his ruthlessness, efficiency, and unwavering loyalty. Menéndez was not merely tasked with dislodging the French; he was to establish a permanent Spanish presence in Florida, secure the coast, and convert the natives to Catholicism. His commission was clear: "take no notice of any person, neither of any King or Prince, to whom he should be obliged."

Menéndez set sail from Spain in June 1565 with a formidable fleet of 19 ships and over 1,500 soldiers, sailors, and settlers – a far larger and better-equipped expedition than any the French had sent. His objective was singular: to destroy Fort Caroline and eliminate the French threat.

The Storm and the Sword

As fate would have it, Jean Ribault, having finally secured substantial reinforcements and supplies, arrived back at the River of May in late August 1565, just as Menéndez’s fleet was making landfall further south. Ribault brought with him seven ships and over 600 additional soldiers and settlers, including women and children, transforming Fort Caroline into a bustling, if still vulnerable, settlement.

The two fleets sighted each other on September 4th. A brief, inconclusive naval skirmish ensued, with Menéndez’s smaller ships unable to effectively engage Ribault’s larger vessels. Menéndez then retreated south, establishing a fortified settlement he named St. Augustine – the first continuously inhabited European settlement in what would become the United States.

Ribault, a seasoned naval commander, recognized the strategic imperative of eliminating the Spanish threat. Despite Laudonnière’s cautious advice to fortify Fort Caroline, Ribault made a fateful decision: he would take the bulk of his fighting men and launch a naval assault on St. Augustine. It was a gamble that would cost him, and the French colony, everything.

As Ribault’s fleet sailed south to engage Menéndez, a powerful hurricane, a force of nature often underestimated by early European explorers, swept through the region. The storm scattered Ribault’s ships, driving them far to the south, many shipwrecking along the treacherous Florida coast.

Menéndez, observing the devastating storm and realizing Fort Caroline would be virtually undefended, seized the opportunity. In an audacious move, he marched his men overland through the hurricane-ravaged wilderness, guided by a captured French deserter. The march was brutal, through swamps and dense forests, in driving rain and wind, but Menéndez drove his men forward with an iron will.

The Massacre at Fort Caroline

On September 20, 1565, after a grueling three-day march, Menéndez and his 500 men launched a surprise dawn attack on Fort Caroline. The French garrison, depleted by Ribault’s absence, weakened by the storm, and lulled into a false sense of security, was caught completely unprepared.

The Spanish assault was swift and merciless. Menéndez’s soldiers swarmed over the palisades, bayoneting and hacking the sleeping or disoriented French. Laudonnière, wounded, managed to escape into the surrounding woods with about two dozen others, eventually making their way back to France. Most of the French soldiers and colonists, however, were slaughtered. Only a handful of women, children, and a few drummers and fifers were spared, taken captive by Menéndez. Estimates vary, but upwards of 130-150 French men were killed in the assault.

Menéndez ordered the bodies of the dead to be hung from trees, a gruesome warning to any who might challenge Spanish dominion. He renamed the captured fort San Mateo and planted the Spanish flag, solidifying Spain’s claim.

The Sands of Matanzas

The tragedy of Fort Caroline was not yet complete. Days later, as Menéndez consolidated his position, reports reached him of shipwrecked Frenchmen gathered south of St. Augustine. These were the survivors of Ribault’s ill-fated fleet, having endured days clinging to wreckage, battling the elements, and struggling along the desolate coast.

Menéndez marched south to confront them, encountering a large group of around 200 survivors, including Ribault himself. The French, exhausted and starving, were trapped on an island cut off by an inlet, a natural barrier that would forever bear the chilling name "Matanzas" – Spanish for "slaughters."

Menéndez, feigning a willingness to offer quarter, demanded their surrender. He asked if they were Catholic or Lutheran. When Ribault responded that they were "of the Reformed religion," Menéndez made his intentions clear. He stated that he had orders from his king to "plant the Gospel in these parts, to the end that the natives may be brought to the knowledge of our Holy Catholic Faith." He then offered them no quarter, only the possibility of confessing their sins.

Over the next few days, in two separate encounters, Menéndez ordered the systematic execution of almost all the shipwrecked Frenchmen. They were led across the inlet in groups of ten, their hands bound, and then summarily executed. Ribault himself was among the last to die. Menéndez famously declared, "I do this not as to Frenchmen, but as to Lutherans, enemies of our holy Catholic faith." This brutal act solidified Spanish control and sent an unambiguous message to any European power contemplating encroachment on La Florida.

A Legacy of Contention and Remembrance

The massacre at Fort Caroline and Matanzas effectively ended France’s first serious attempt at colonization in Florida. Though a retaliatory French expedition led by Dominique de Gourgues in 1568 briefly recaptured and burned Fort San Mateo, executing its Spanish garrison in revenge for Ribault, it was a symbolic victory that did not alter the geopolitical reality. Spain remained the undisputed European power in Florida for the next two centuries.

For centuries, the story of Fort Caroline largely faded from popular memory, overshadowed by the more "successful" English colonies to the north. However, in the 20th century, historical research and archaeological efforts brought this dramatic chapter back into focus. The Fort Caroline National Memorial was established in 1950, and a reconstructed version of the triangular fort was built in 1964, commemorating the 400th anniversary of its founding.

Today, visitors to the memorial can walk the grounds where Laudonnière’s men once toiled and fought, imagining the hardships and the ultimate terror that befell them. While the exact location of the original fort remains a subject of ongoing debate among historians and archaeologists (the reconstructed fort is a symbolic representation, believed to be very close to the actual site), the memorial serves as a powerful reminder of the complex forces that shaped early America.

Fort Caroline stands as a stark lesson in the raw, often brutal, realities of European expansion. It highlights the potent mix of religious fervor, national ambition, and sheer human desperation that characterized the age of exploration. It reminds us that the "discovery" of the New World was not a benign process, but a clash of cultures, faiths, and empires, often culminating in violence and tragedy. The echoes of those struggles, the dreams of refuge, and the cries of those slaughtered, linger still along the tranquil banks of the St. Johns River, urging us to remember a crucial, yet often overlooked, beginning.