Echoes of the Hoofbeat: The Enduring Legend of America’s Ellsworth Cattle Trail

The American West, a landscape etched into the global imagination, is a tapestry woven with tales of daring, hardship, and transformation. It’s a place where myth and history often intertwine, giving rise to legends that continue to captivate. While names like Abilene and Dodge City often dominate the narrative of the great cattle drives, a lesser-sung, yet equally potent, legend resides in the annals of Kansas: the Ellsworth Cattle Trail. For a brief, incandescent period in the early 1870s, Ellsworth was a roaring nexus of the cattle trade, a boomtown that embodied the raw, untamed spirit of the frontier and played a crucial role in shaping the economic and cultural landscape of a burgeoning nation.

To understand the legend of Ellsworth, one must first grasp the vast forces that converged to create it. The end of the Civil War in 1865 left Texas with an estimated five million longhorn cattle, a resilient breed perfectly adapted to the harsh Southern plains. These cattle, however, were worth a mere pittance in Texas, perhaps $3 to $5 a head. Meanwhile, the rapidly industrializing cities of the East, recovering from the war and experiencing a population boom, clamored for beef. The solution was as audacious as it was simple: drive the cattle north to the railheads in Kansas, where they could be loaded onto trains and shipped to market, fetching prices as high as $30 to $50 a head.

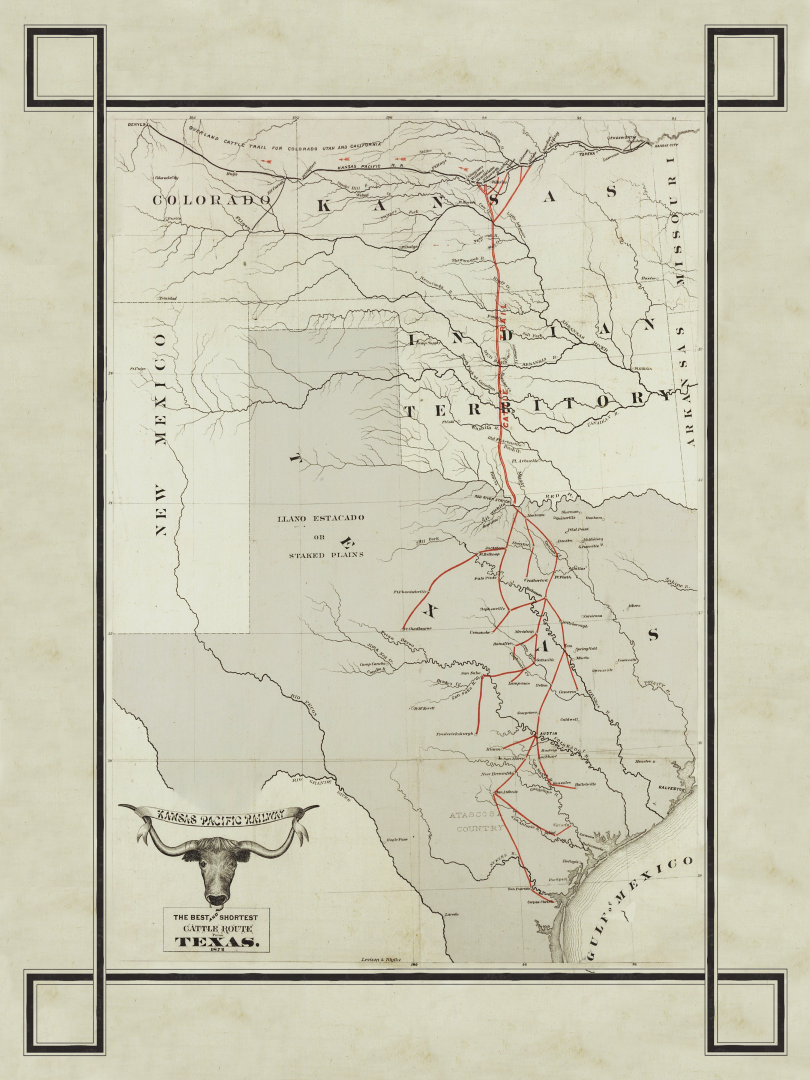

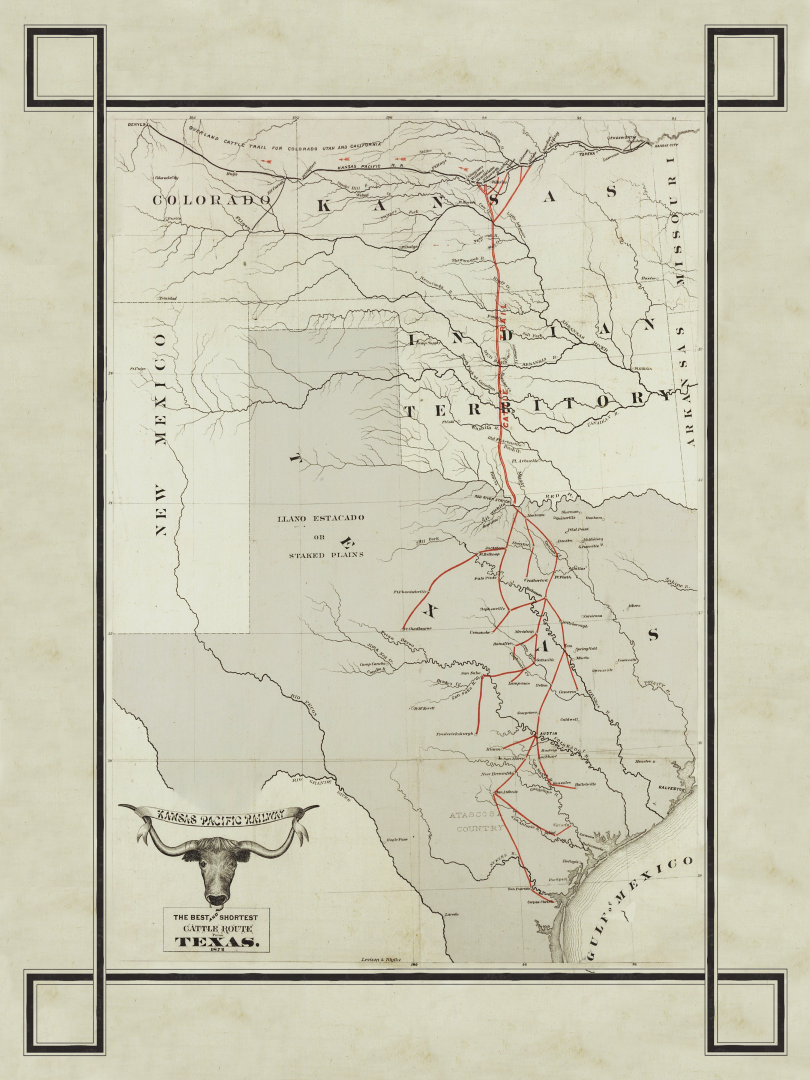

This economic imperative sparked one of the most iconic phenomena in American history: the cattle drive. Joseph G. McCoy, a visionary entrepreneur, is credited with establishing Abilene, Kansas, as the first major "cow town" in 1867, recognizing its strategic location on the Kansas Pacific Railway. Abilene’s success proved the concept, and soon, other towns vied for a share of the lucrative cattle trade. Among these contenders, Ellsworth would rise to prominence, carving its own distinct, if short-lived, legend.

Ellsworth, nestled on the banks of the Smoky Hill River and served by the Kansas Pacific Railway, emerged as a significant cattle market around 1872. It was strategically located further west than Abilene, offering a more direct route for drovers pushing herds from central and western Texas. For a few intense years, Ellsworth became the preferred destination for countless herds, attracting cowboys, cattle buyers, merchants, and a motley crew of opportunists, outlaws, and lawmen.

The trail to Ellsworth was not merely a path; it was a crucible. The journey, spanning hundreds of miles and lasting anywhere from two to three months, was an epic test of endurance for both man and beast. Tens of thousands of Texas Longhorns, known for their lean muscle, impressive horns, and ability to thrive on sparse forage, would be herded north. Accompanying them were the cowboys – a diverse group comprising former Confederate soldiers, freed slaves, Mexican vaqueros, and young men from all walks of life seeking adventure and opportunity.

Life on the trail was a relentless cycle of sun-up to sundown labor. Cowboys spent their days in the saddle, pushing the herd, navigating treacherous rivers, enduring dust storms, and guarding against stampedes. Nights were spent under the vast prairie sky, with men taking turns on watch, their lonesome songs echoing across the plains to soothe the restless cattle. "It ain’t just a job, it’s a way of life," an old drover was quoted in contemporary accounts, reflecting the profound dedication and hardship. "You eat dust, drink mud, and sleep with one eye open, but there’s a freedom out here you won’t find nowhere else." The dangers were manifold: flash floods, prairie fires, rattlesnakes, and the constant threat of rustlers and Native American raiding parties, though the latter diminished significantly by the time Ellsworth peaked due to peace treaties and the establishment of reservations.

Upon reaching Ellsworth, the dusty, weary cowboys found a town transformed. What might have been a sleepy frontier outpost swelled into a boisterous, lawless hub of commerce and revelry. Saloons, gambling halls, dance houses, and general stores sprang up overnight, catering to the needs and desires of men who had just endured months of isolation and deprivation, and who now had pockets full of hard-earned cash. The town’s population would explode during the trailing season, making it a microcosm of the Wild West myth.

This influx of men, money, and raw energy inevitably led to conflict. Ellsworth quickly gained a reputation for its wildness. Shootouts were not uncommon, and the line between law and lawlessness was often blurred. Maintaining order fell to a handful of brave, often ruthless, lawmen. One notable figure who briefly served as a deputy marshal in Ellsworth in 1873 was none other than Wyatt Earp. Before his legendary exploits in Tombstone, Earp cut his teeth in these Kansas cow towns, grappling with the challenges of a frontier community bursting at the seams. His presence, however brief, adds another layer of intrigue to Ellsworth’s story, linking it directly to some of the most iconic figures of the Old West.

The economic impact of the cattle trade on Ellsworth was immense. Millions of dollars flowed through its businesses, stimulating growth and attracting investment. The town became a melting pot of cultures, where the rough-hewn Texan drovers mingled with Eastern cattle buyers, local farmers, and various immigrant groups seeking their fortune. This fusion of backgrounds and ambitions created a dynamic, if chaotic, social environment that was uniquely American.

However, the golden age of Ellsworth, like many cow towns, was destined to be fleeting. Several factors conspired to bring about its decline. Perhaps the most significant was the growing conflict between the cattlemen and the burgeoning agricultural settlements. Farmers, moving westward and fencing off the open range, increasingly resented the cattle drives, which trampled crops and spread "Texas fever" – a tick-borne disease deadly to domestic cattle, though harmless to the immune Longhorns. Kansas began enacting "quarantine laws," pushing the cattle trails further west, away from settled areas.

The expansion of the railroad network also played a pivotal role. As rail lines extended deeper into Texas, the need for long-distance drives to Kansas diminished. Towns like Fort Worth and Wichita emerged as new, closer railheads, siphoning off the herds that once flowed to Ellsworth. By 1875, the glory days of Ellsworth as a premier cow town were largely over, its brief but brilliant flame extinguished by progress and changing landscapes.

Despite its relatively short reign, the Ellsworth Cattle Trail left an indelible mark on the American narrative. It contributed significantly to the economic development of both Texas and the nation, providing a crucial link in the food supply chain and fueling the growth of the burgeoning beef industry. More profoundly, it solidified the image of the American cowboy as a national icon – a symbol of rugged individualism, resilience, and a deep connection to the land.

The legend of Ellsworth, though perhaps less universally recognized than that of Abilene or Dodge City, is no less vital. It reminds us that the Wild West was not a monolithic entity, but a collection of unique stories, each town and trail contributing its own distinct chapter to the larger saga. The echoes of thundering hooves, the shouts of the drovers, the raucous sounds of a boomtown saloon, and the quiet courage of its lawmen – all these elements form the enduring legend of the Ellsworth Cattle Trail. It is a testament to a time when vast landscapes, economic necessity, and human ambition converged to create an epic chapter in American history, a chapter that continues to resonate in the collective memory of a nation fascinated by its own frontier past. The dust may have settled on the trail, and the cattle cars long gone, but the spirit of Ellsworth, a wild and vibrant symbol of the American West, continues to live on in the legends it helped to forge.