Echoes of the Last Stand: The Great Sioux War of 1876

The year 1876 shimmered with the promise of a burgeoning nation, celebrating its centennial with parades, fireworks, and a profound sense of manifest destiny. Yet, a thousand miles to the west, in the rugged, sun-baked expanses of the northern plains, another narrative was unfolding – one of defiance, betrayal, and bloodshed. This was the stage for the Great Sioux War, a cataclysmic clash between the burgeoning power of the United States and the determined, free-roaming Lakota Sioux and Northern Cheyenne. It was a conflict born of broken treaties, unbridled ambition, and a fundamental misunderstanding between two vastly different cultures, culminating in the most iconic and devastating defeat for the U.S. Army on the frontier: the Battle of the Little Bighorn.

At its heart, the war was a direct consequence of the 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie. This agreement, ostensibly designed to bring peace, established the Great Sioux Reservation, encompassing a vast tract of land, and crucially, recognized the sacred Black Hills (Paha Sapa) as unceded Indian Territory, explicitly off-limits to white settlement. For the Lakota, the Black Hills were more than just land; they were the spiritual heart of their universe, a place of profound religious significance where visions were sought and ancient ceremonies performed. "The Black Hills are like our church," a Lakota elder might have explained, "our sacred place where the Great Spirit dwells."

However, the ink on the treaty was barely dry when rumors of gold in the Black Hills began to circulate. These whispers were confirmed in 1874 by an exploratory expedition led by the flamboyant Civil War hero, Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer. His report, eagerly amplified by the press, sparked a full-blown gold rush. Thousands of prospectors, ignoring the treaty, swarmed into the sacred hills, tearing at the earth, desecrating holy sites, and trampling over Lakota sovereignty.

The U.S. government found itself in a dilemma. It could either uphold the treaty and forcibly remove the miners, risking a public outcry from an economically struggling nation eager for new wealth, or it could seize the Black Hills. Unsurprisingly, the latter course was chosen. Negotiations were initiated to purchase the Black Hills, but the Lakota, led by spiritual leaders like Sitting Bull and war chiefs like Crazy Horse, steadfastly refused. "I want no white man to come here," Sitting Bull famously declared. "The Black Hills are mine. I am willing to fight for them."

When negotiations failed, the government resorted to an ultimatum. In December 1875, it ordered all Lakota and Cheyenne who had not reported to their designated agencies by January 31, 1876, to be considered "hostile" and subject to military action. This was an impossible demand; winter conditions made travel across the plains virtually impassable. It was, in essence, a declaration of war.

The military strategy devised by President Ulysses S. Grant and General Philip Sheridan was a classic "hammer and anvil" approach. Three columns of troops were to converge on the unceded territory, trapping and forcing the "hostiles" onto reservations. General George Crook would advance from the south, Colonel John Gibbon from the west, and General Alfred Terry, with Custer’s 7th Cavalry attached, from the east.

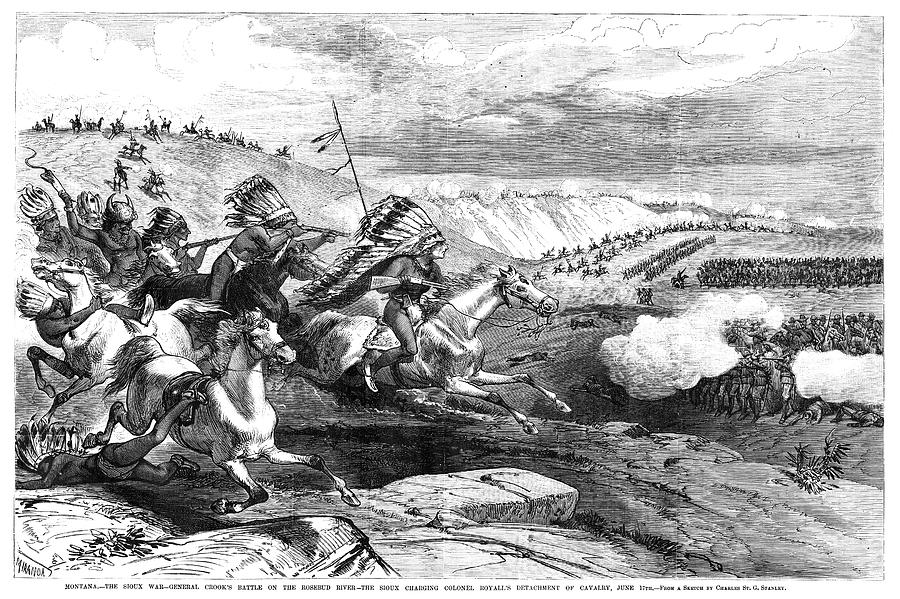

The first major engagement of the war came on June 17, 1876, at the Battle of the Rosebud. General Crook’s column, numbering around 1,000 soldiers and 300 Crow and Shoshone scouts, encountered a formidable force of Lakota and Cheyenne warriors led by Crazy Horse. The Lakota, forewarned by Sitting Bull’s vision of soldiers falling into his camp, launched a fierce, well-coordinated attack. The fighting lasted for hours, a brutal, swirling melee across the broken terrain. Though often considered a tactical draw, the Battle of the Rosebud was a crucial strategic victory for the Natives. Crazy Horse’s warriors inflicted significant casualties and, more importantly, forced Crook to retreat and regroup, preventing him from linking up with Terry and Gibbon. This delay would have dire consequences for Custer.

Just eight days later, on June 25, 1876, the stage was set for the most infamous event of the war. General Terry, unaware of Crook’s setback, had ordered Custer to scout ahead with the 7th Cavalry, locate the Native encampment, and prevent its escape, but to await Terry and Gibbon’s main force before attacking. Custer, driven by ambition and a desire for glory, disobeyed these orders. Spotting what he believed to be a relatively small village in the valley of the Little Bighorn River (which the Lakota called Greasy Grass), he decided to attack immediately, fearing the villagers would scatter.

In a move that remains hotly debated by historians, Custer divided his regiment into three battalions. Major Marcus Reno was ordered to charge the southern end of the village, Captain Frederick Benteen was sent to scout to the left, and Custer, with five companies, took the ridge to the right, planning a flanking maneuver. What Custer fatally underestimated was the sheer size of the Native encampment. It was, in fact, one of the largest gatherings of Plains Indians in history, numbering perhaps 7,000-10,000 people, including 1,500-2,000 warriors, under the unified leadership of Sitting Bull, Crazy Horse, Gall, and others.

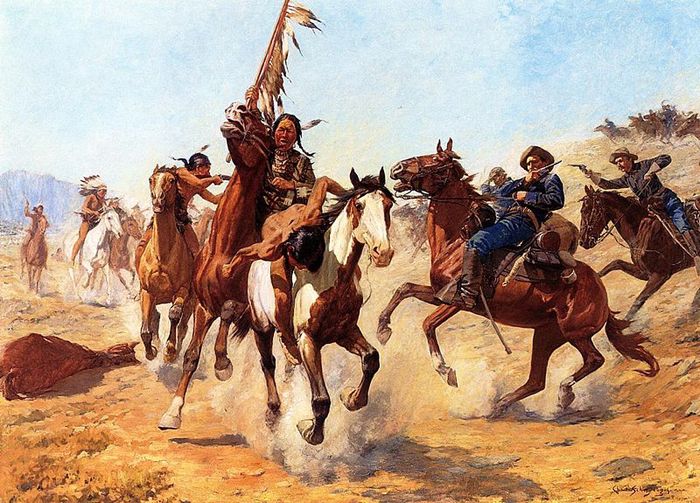

Reno’s attack quickly faltered. Overwhelmed by the sheer numbers of warriors pouring out of the village, his men were driven back, suffering heavy losses as they retreated to a defensive position on a nearby hill. Meanwhile, Custer’s command, attempting to attack the northern end of the village, was met by a determined and overwhelming Native counterattack. Warriors, led by Crazy Horse and Gall, swarmed Custer’s position on what became known as "Last Stand Hill." The battle was swift and brutal. Within hours, Custer and all 209 men under his direct command were annihilated.

The news of Custer’s Last Stand, arriving on the heels of the nation’s centennial celebrations, sent shockwaves across America. It was an unthinkable defeat, a national humiliation. Newspapers, initially incredulous, soon fueled public outrage and demands for retribution. The image of the valiant Custer, outnumbered but fighting to the last, became a powerful, if inaccurate, myth that spurred the government to redouble its efforts to "pacify" the Plains.

The defeat galvanized the U.S. Army. Generals Crook and Terry, now reinforced, launched relentless winter campaigns. The strategy shifted to one of attrition, targeting Native food supplies, horses, and shelter, making survival through the harsh winter months nearly impossible. In September 1876, Colonel Ranald S. Mackenzie’s troops attacked a Lakota village at Slim Buttes, the first significant engagement after Little Bighorn, recovering Custer’s guidon and capturing a large number of horses.

Even more devastating was the Dull Knife Fight in November 1876. Colonel Mackenzie’s Fourth Cavalry destroyed a Cheyenne village in the Big Horn Mountains, seizing their horses and burning their lodges and winter supplies. The Cheyenne survivors, including women and children, were forced to flee in sub-zero temperatures, many freezing or starving to death. These relentless pursuits and the destruction of their resources began to break the will of the Lakota and Cheyenne.

By the spring of 1877, facing starvation and constant harassment, many bands began to surrender and return to their agencies. Crazy Horse, the brilliant warrior who had led the charge at Rosebud and Little Bighorn, finally surrendered at Fort Robinson, Nebraska, in May 1877. His freedom, however, was short-lived. Four months later, on September 5, 1877, under suspicious circumstances, he was fatally bayoneted by a guard while reportedly resisting imprisonment. "My lands are where my dead lie buried," he is often quoted as saying, encapsulating his deep connection to the land and his people.

Sitting Bull, refusing to surrender, led his Hunkpapa Lakota band into Canada, seeking asylum. They remained there for several years, but the buffalo herds, their primary food source, were dwindling rapidly. Faced with starvation, Sitting Bull and his followers eventually returned to the U.S. in 1881 and surrendered. He was held as a prisoner of war for two years before being released to the Standing Rock Agency, where he continued to be a symbol of resistance until his tragic death in 1890 during an attempt by agency police to arrest him.

The Great Sioux War of 1876 marked the definitive end of the era of free-roaming Plains Indians. The Lakota and Cheyenne lost their ancestral lands, particularly the sacred Black Hills, which were illegally seized by Congress in 1877. They were confined to reservations, their traditional way of life shattered, their cultures systematically dismantled through forced assimilation policies. The war left an indelible scar on both sides. For the U.S., it solidified its control over the West, but at the cost of its moral standing and through actions that continue to be debated and lamented. For the Lakota and Cheyenne, it was the bitter culmination of a centuries-long struggle for sovereignty, a poignant testament to their courage and resilience in the face of overwhelming odds. The echoes of the Last Stand continue to resonate, a powerful reminder of the complex and often tragic tapestry of American history.