Echoes of the Plains: The Cheyenne Raids and the Forging of an American Legend

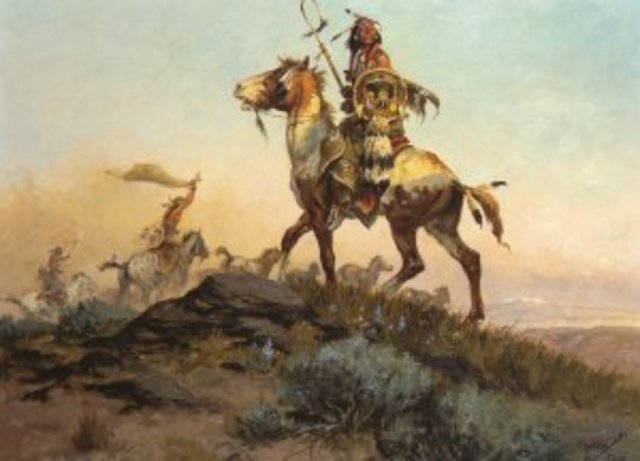

The American West, a landscape etched into the global imagination, is a tapestry woven from myth and harsh reality. It’s a land of stoic cowboys, intrepid pioneers, and the noble, often tragic, figures of Native American resistance. Among the myriad legends that sprang from this tumultuous era, few encapsulate the brutal clash of cultures, the desperation for survival, and the enduring legacy of conflict as vividly as the Cheyenne raids across the Kansas plains in the late 1860s. These were not mere skirmishes; they were a desperate outcry, a brutal reprisal, and a defining chapter in the violent saga of westward expansion, forging a legend that continues to resonate today.

Kansas in the mid-19th century was the frontier’s beating heart, a promised land for homesteaders drawn by the allure of cheap land and the promise of a new life. Railroads, symbols of progress, snaked across the prairie, bringing settlers, trade, and irrevocably altering the ancient hunting grounds of the Plains tribes. For the Cheyenne, particularly the fiercely independent band known as the Dog Soldiers, this relentless encroachment was an existential threat. Their way of life, intrinsically linked to the buffalo and the vast, open spaces, was being systematically dismantled by the very forces that promised a brighter future for the newcomers.

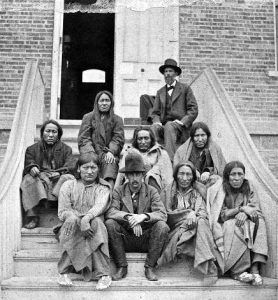

The stage for conflict was set by a litany of broken treaties and misunderstandings. The Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851 and the subsequent Medicine Lodge Treaty of 1867 had attempted to define boundaries and ensure peace, but the ink was barely dry before the agreements were violated, often by the very government that ratified them. The buffalo, the lifeblood of the Cheyenne, were being slaughtered by hide hunters, and annuities promised in exchange for land rarely materialized. Added to this simmering resentment was the lingering horror of the Sand Creek Massacre in 1864, where Colonel John Chivington’s Colorado militia brutally attacked a peaceful village of Cheyenne and Arapaho, killing women, children, and the elderly under a white flag. This act of barbarism shattered any remaining trust and ignited a burning desire for revenge among many Cheyenne, especially the Dog Soldiers, who refused to be confined to reservations.

The Summer of Terror: 1868

By the summer of 1868, the tension was palpable. Drought had withered crops on the reservations, and the buffalo herds were dwindling. Starvation loomed. The Dog Soldiers, under leaders like Tall Bull and Roman Nose, knew their people faced a choice: succumb to the reservation’s slow death or fight for their survival and their ancestral lands. They chose the latter, unleashing a series of coordinated, devastating raids across western Kansas that would engrave their name in the annals of frontier history.

The targets were clear: isolated homesteads, stagecoach lines, and small settlements along the Solomon and Saline River valleys. These were the very symbols of the encroaching white world. Beginning in August, Cheyenne warriors swept through the region, driven by a desperate need for horses, supplies, and, in many cases, a raw, visceral desire for vengeance. The raids were swift and brutal. Homes were plundered and burned, livestock driven off, and settlers, both men and women, were killed or taken captive.

One particularly harrowing account from the period describes the terror that gripped the settlers. "The air was thick with fear," wrote a contemporary newspaper correspondent, "Every rustle of the prairie grass, every distant dust cloud, sent chills down the spines of the homesteaders." The raids were not random acts of savagery, as they were often portrayed in the sensationalist press of the day. From the Cheyenne perspective, they were acts of war, a desperate defense of their homeland and their culture against an overwhelming tide. They saw themselves as warriors protecting their families and their way of life, striking back at those who had stolen their future.

The Military Response and the Cycle of Violence

The U.S. Army, under the command of figures like General Philip Sheridan and later, the flamboyant George Armstrong Custer, responded with a grim determination to "solve the Indian problem." Sheridan famously declared, "The only good Indian is a dead Indian," a sentiment that, whether accurately attributed or not, certainly reflected the prevailing military attitude towards Native American resistance. The raids in Kansas provided the impetus for a full-scale winter campaign designed to crush the tribes once and for all.

One of the most famous engagements directly related to these Kansas raids, though occurring just across the border in Colorado, was the Battle of Beecher Island in September 1868. A small detachment of U.S. Army scouts, under Major George Forsyth, was ambushed by a much larger force of Cheyenne, Arapaho, and Sioux warriors, including the legendary Roman Nose. The scouts dug in on a sandbar in the Arikaree River and endured a desperate siege for days. Though suffering heavy casualties, including Forsyth, they held out until relief arrived. Beecher Island became a symbol of frontier bravery for the settlers, showcasing the fierce determination of both sides.

The military’s strategy, particularly during the harsh winter months, was to destroy the Cheyenne’s ability to wage war by targeting their villages, ponies, and winter supplies. This culminated in the Washita Massacre in November 1868, where Custer’s 7th Cavalry attacked Black Kettle’s Southern Cheyenne village in present-day Oklahoma. Black Kettle, a peace chief who had survived Sand Creek, was killed along with many of his people, primarily women and children. While not a direct Kansas raid, the Washita Massacre was a direct consequence of the escalated conflict and further fueled the cycle of violence and despair. It demonstrated the military’s brutal efficiency and its willingness to strike at non-combatants, further hardening the resolve of the remaining Dog Soldiers.

The Fading Roar of Resistance

The relentless pressure, the destruction of their food sources, and the constant pursuit by the army began to take their toll on the Dog Soldiers. By 1869, their numbers were dwindling, and their resources stretched to breaking point. The last major engagement involving the Dog Soldiers in Kansas was the Battle of Summit Springs in July 1869, where a force under General Eugene Carr, guided by Pawnee scouts, surprised Tall Bull’s village. Tall Bull was killed, and his band was decimated. This battle effectively broke the back of the Dog Soldier resistance.

The legacy of the Cheyenne raids in Kansas is complex and deeply etched into the American narrative. For the homesteaders and their descendants, these events became tales of terror and resilience, of a brave new world being carved out against incredible odds. The Cheyenne warriors were often cast as "savages," a dangerous impediment to progress, whose violent acts justified the harsh military response. The legends spoke of fear, loss, and the courage of those who dared to settle the frontier.

However, from the Cheyenne perspective, the raids represent a desperate, heroic stand against cultural annihilation. They were a fight for freedom, for the right to live according to their traditions, and for the very survival of their people. "We did not want war," a Cheyenne elder was later quoted as saying, "but they came and took everything. What choice did we have but to fight for our children?" Their legends tell of brave warriors, strategic genius, and an unwavering commitment to their ancestors and their way of life, even in the face of insurmountable odds.

A Legacy of Contradictions

Today, the legends of the American West are being re-examined, stripped of some of their romanticized veneer to reveal the often-painful truths beneath. The Cheyenne raids in Kansas, once a simple tale of "Indians vs. settlers," are now understood as a tragic chapter born of profound cultural misunderstanding, broken promises, and the inexorable march of Manifest Destiny. They highlight the devastating consequences of colonial expansion and the profound human cost of progress.

These events left an indelible mark on the landscape and the collective memory of America. They solidified the image of the "Wild West" as a place of raw courage and brutal violence, where legends were born in the crucible of conflict. The tales of Cheyenne warriors sweeping across the plains and the harrowing experiences of the settlers became foundational stories in the construction of American identity – stories of resilience, pioneering spirit, and the enduring struggle for land and survival.

The Kansas plains, once echoing with the thundering hooves of buffalo and the desperate cries of battle, now mostly whisper with the wind through cornfields. Yet, the legends of the Cheyenne raids remain, a powerful reminder of the complex, often contradictory, forces that shaped a nation. They are not merely historical footnotes but living narratives that challenge us to look beyond simplistic heroes and villains, to understand the multi-faceted perspectives of a past that continues to inform our present, urging us to acknowledge the full human story behind the myths of the American frontier.