Echoes of the Prairie: Unearthing the Legacies of Historic South Dakota People

South Dakota, a land of vast prairies, dramatic badlands, and the ancient Black Hills, is more than just a geographic marvel; it is a living tapestry woven with the indelible threads of human stories. From the spiritual leaders of the Lakota to the rugged pioneers, the ambitious prospectors, and the visionary politicians, the historic people of South Dakota have shaped not only the state but also the narrative of America itself. Their legacies, often etched into the very landscape, resonate through time, offering profound insights into courage, conflict, and the enduring human spirit.

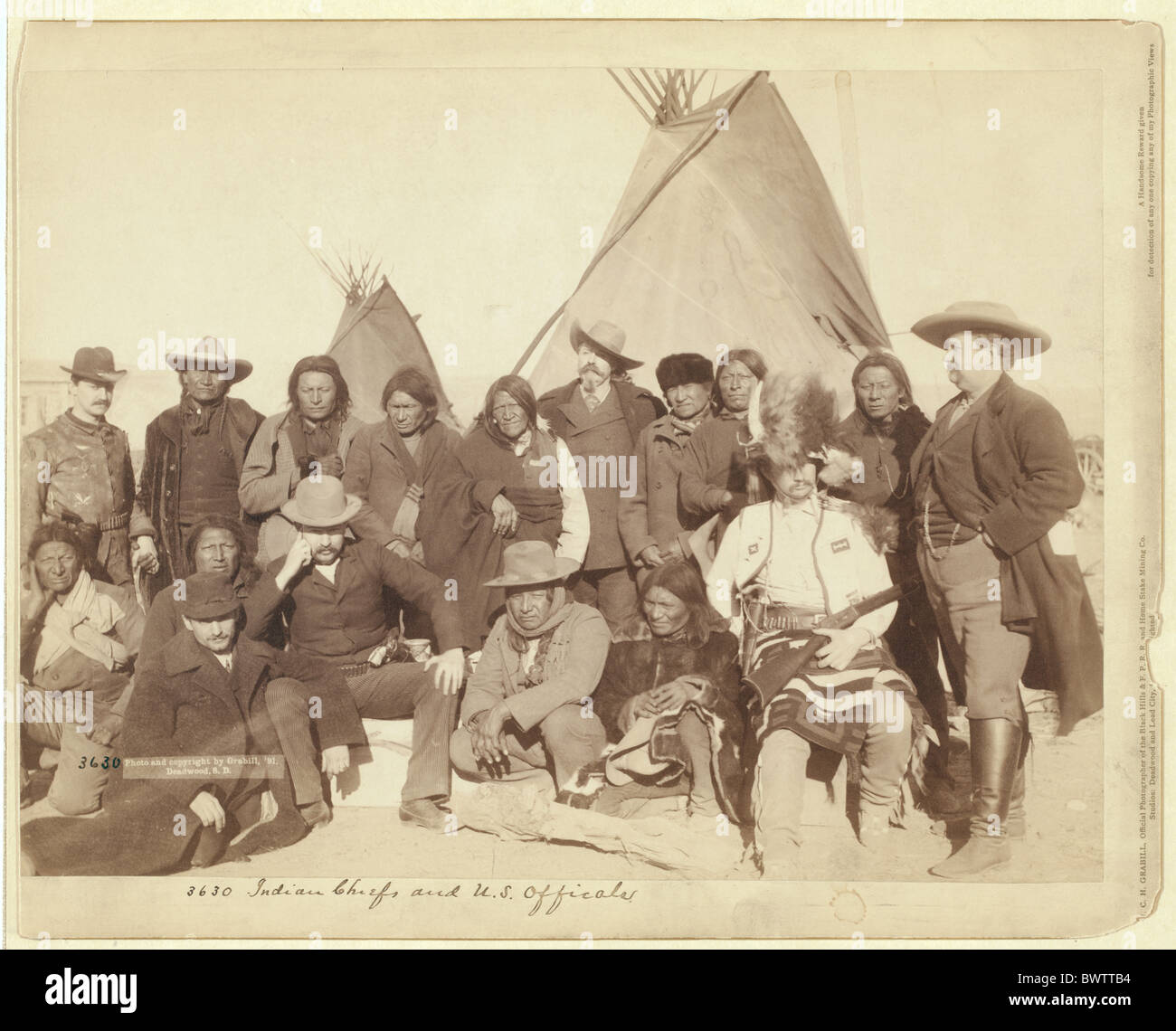

At the heart of South Dakota’s historical identity lie the Oceti Sakowin (Seven Council Fires), the Dakota, Lakota, and Nakota nations, who have called this land home for centuries. Their connection to the sacred Black Hills (Paha Sapa) and the Missouri River is foundational. Among the pantheon of their great leaders, several figures stand out, embodying resistance, wisdom, and an unwavering commitment to their people and their way of life.

Perhaps no name evokes the spirit of defiance more powerfully than Sitting Bull (Tatanka Iyotake), the Hunkpapa Lakota holy man and chief. Born around 1831 in what is now South Dakota, Sitting Bull was a pivotal figure in the Lakota resistance against the encroaching American government. He was not just a warrior, but a spiritual leader whose visions guided his people. His refusal to cede lands or compromise on sovereignty made him a symbol of Indigenous resilience. He famously declared, "Let us put our minds together and see what life we can make for our children." This sentiment, rooted in communal well-being, defined his leadership. His strategic genius was evident at the Battle of the Little Bighorn in 1876, where his vision of soldiers falling upside down came to pass, leading to one of the most significant Native American victories against the U.S. Army. His eventual surrender and tragic death in 1890, just days before the Wounded Knee Massacre, marked the end of an era but cemented his place as an enduring icon of resistance.

Alongside Sitting Bull, Crazy Horse (Tȟašúŋke Witkó), an Oglala Lakota warrior, remains an enigmatic and revered figure. Known for his exceptional bravery, tactical brilliance, and reclusive nature – he famously refused to be photographed – Crazy Horse was a master of guerrilla warfare. He played a crucial role in the Fetterman Fight (1866) and the Battle of the Little Bighorn, where his leadership on the battlefield was decisive. His deep spiritual connection to the land and his people fueled his unwavering fight to preserve their way of life. Unlike many contemporaries, he never signed a treaty with the U.S. government. His surrender in 1877, under the promise of a peaceful life for his people, was followed by his death while resisting imprisonment – a poignant symbol of the broken promises and tragic end of the Plains Wars. Today, the monumental Crazy Horse Memorial, still under construction in the Black Hills, stands as a testament to his legacy and a symbol of Native American pride and history.

Another formidable leader was Red Cloud (Maȟpíya Lúta), an Oglala Lakota chief who achieved a rare feat: winning a war against the United States. During "Red Cloud’s War" (1866-1868), he successfully resisted the construction of forts along the Bozeman Trail, a route through prime Lakota hunting grounds. The subsequent Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868 granted the Lakota vast territory, including the Black Hills, as unceded lands. Red Cloud’s strategic brilliance and his ability to unite various Lakota bands demonstrated a powerful diplomatic and military force. Though later advocating for peace and adaptation, his early victories secured significant, albeit temporary, victories for his people.

The spiritual depth of the Lakota people is perhaps best embodied by Black Elk (Heȟáka Sápa), an Oglala Lakota holy man and healer. Born in 1863, Black Elk was a cousin of Crazy Horse and witnessed many of the transformative events of his era, including the Battle of the Little Bighorn and the Wounded Knee Massacre. His profound spiritual visions, which he experienced from a young age, became the subject of the seminal book Black Elk Speaks (as told to John G. Neihardt). This book offered an unparalleled insight into Lakota spirituality, cosmology, and the devastating impact of colonization on Indigenous cultures. Black Elk’s narrative is a poignant lament for a lost way of life, yet also a powerful testament to the enduring strength of his people’s spiritual traditions.

As the 19th century progressed, the lure of gold and land brought a new wave of people to South Dakota. The discovery of gold in the Black Hills in 1874, an area protected by treaty for the Lakota, ignited a gold rush that irrevocably altered the region. This influx brought figures who, though perhaps less revered, became indelible parts of South Dakota’s rugged history.

Wild Bill Hickok (James Butler Hickok), the legendary lawman, gunfighter, and gambler, spent his final days in Deadwood. His arrival in 1876, seeking fortune in the gold fields, was brief but dramatic. On August 2, 1876, he was shot in the back of the head while playing poker, holding what famously became known as the "dead man’s hand" – aces and eights. His murder, and the subsequent trial of his killer, Jack McCall, cemented Deadwood’s reputation as a wild and lawless frontier town. Hickok embodies the transient, often violent, nature of the gold rush era.

Equally iconic, though perhaps more of a folk legend, was Calamity Jane (Martha Jane Cannary). An expert marksman and horseback rider, she cut an unconventional figure in the male-dominated frontier. Her life was a blur of nursing the sick during smallpox outbreaks, working as a scout, and performing in Wild West shows. She was known for her hard-drinking, storytelling, and often exaggerated tales of her adventures. She too ended up in Deadwood, where she became associated with Hickok, and is buried beside him, further intertwining their legends in the annals of South Dakota history.

Beyond the gold rush, the promise of fertile land drew homesteaders and pioneers to the vast prairies. These were the ordinary men and women who endured harsh winters, droughts, and isolation to build farms and communities from scratch. Their stories, though often unsung, are the bedrock of the state’s agricultural heritage.

One of the most beloved chroniclers of this era was Laura Ingalls Wilder. While not born in South Dakota, her formative years and the setting for much of her immensely popular "Little House" book series were in the small town of De Smet. Her vivid descriptions of prairie life, building a home, surviving blizzards, and the simple joys and hardships of homesteading provided generations of readers with an intimate glimpse into the pioneer experience. Her books, like By the Shores of Silver Lake and The Long Winter, are not just children’s stories; they are historical documents, capturing the spirit and resilience of the people who settled the Dakotas.

As the 20th century dawned, South Dakota began to forge a more modern identity, guided by leaders with grand visions for the state. Peter Norbeck, a Norwegian immigrant’s son, rose from well-digger to governor and then U.S. Senator. He was a true conservationist and visionary. Norbeck was instrumental in establishing Custer State Park, preserving the Needles Highway, and creating the Iron Mountain Road – engineering marvels that integrated the natural beauty of the Black Hills with human access. Crucially, Norbeck was the driving force behind the creation of Mount Rushmore National Memorial. His perseverance in securing federal funding and his strategic partnership with the sculptor were pivotal. His dedication to public lands and his foresight in developing infrastructure for tourism laid the groundwork for South Dakota’s modern economy and identity.

The man who carved the faces of four presidents into the granite of Mount Rushmore was Gutzon Borglum. A controversial but undeniably brilliant sculptor, Borglum brought an almost fanatical zeal to his monumental task. He envisioned the colossal heads as a lasting tribute to American democracy and its foundational figures. Despite constant financial struggles, technical challenges, and his own difficult personality, Borglum dedicated the last 14 years of his life to Mount Rushmore, leaving behind a work that symbolizes South Dakota to the world. His ambition and artistic vision transformed a mountainside into a national shrine.

In a powerful counterpoint to Mount Rushmore, the dream of Korczak Ziolkowski became the Crazy Horse Memorial. A Polish-American sculptor who worked on Mount Rushmore for a time, Ziolkowski was invited by Lakota Chief Henry Standing Bear to carve a monument to the Native American spirit, a response to the perceived imbalance of Rushmore. Ziolkowski dedicated his entire life to this monumental undertaking, living in the Black Hills and personally blasting and carving the mountain. Though unfinished at his death in 1982, and continuing under the guidance of his family, the Crazy Horse Memorial is a testament to one man’s unwavering commitment and a powerful symbol of Native American pride and the ongoing effort to tell their story.

From the fierce independence of Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse, to the quiet perseverance of the homesteaders like Laura Ingalls Wilder, and the bold visions of Peter Norbeck and Gutzon Borglum, the historic people of South Dakota collectively paint a vibrant portrait of a state forged by diverse forces. Their struggles, triumphs, and enduring spirits continue to define South Dakota, inviting all who visit to listen to the echoes of the prairie and reflect on the profound human narratives etched into its rugged heartland. Their legacies remind us that history is not just a collection of dates, but a living narrative shaped by extraordinary individuals whose impact continues to reverberate through time.