Echoes of the River: The Enduring Spirit of Maine’s Unrecognized Kennebec Nation

Along the sinuous path of Maine’s Kennebec River, a story of profound resilience, deep-rooted identity, and an ongoing struggle for recognition flows like the ancient waters themselves. This is the story of the Kennebec people, a distinct community whose historical presence shaped the very landscape of the Dawnland, yet whose modern existence often remains unseen by the broader American public. Unlike their federally recognized Wabanaki relatives – the Penobscot, Passamaquoddy, Maliseet, and Micmac – the Kennebec Nation, as a distinct sovereign entity, navigates a complex world without the legal protections and resources that come with federal acknowledgement. Their narrative is a powerful testament to the enduring spirit of Indigenous people, a journey marked by ancient traditions, devastating loss, and an unwavering commitment to cultural survival.

For millennia, the Kennebec River was the lifeblood of the people who called themselves "Norridgewock" or "Kennebec," names that speak to their deep connection to the land and the river that bore their identity. They were a part of the larger Abenaki confederacy, a network of Algonquian-speaking peoples whose territories stretched across what is now northern New England and southeastern Canada. Their traditional homeland encompassed the vast watershed of the Kennebec, from its headwaters in the mountains to its mouth on the Atlantic Ocean.

Life was a seasonal rhythm, dictated by the bounty of the land and water. The Kennebec were expert hunters, fishers, and gatherers, moving with the seasons to harvest resources. Spring brought the vital runs of salmon and alewives upriver, a time for communal fishing and sustenance. Summer was spent cultivating corn, beans, and squash in fertile riverine plots, while foraging for berries and medicinal plants. Autumn saw them venturing into the forests for moose, deer, and bear, preparing for the harsh Maine winter. Their villages, often strategically located at rapids or portage points, were vibrant centers of community, where oral traditions were passed down, ceremonies were held, and complex social structures governed their lives.

"Our ancestors understood the interconnectedness of all things," explains an elder, her voice echoing a wisdom passed down through generations. "The river was not just a source of food; it was our highway, our spiritual guide, the very pulse of our existence. Every tree, every stone, every creature held a lesson, a spirit. This deep understanding of stewardship, of living in balance, is what we strive to reclaim and teach today."

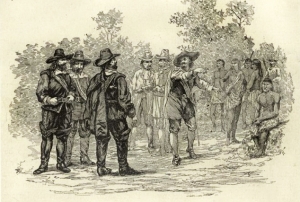

The arrival of Europeans in the early 17th century irrevocably altered this ancient way of life. Initial encounters were often driven by the lucrative fur trade, with the Kennebec exchanging beaver pelts for European goods like metal tools, cloth, and firearms. While these early interactions offered novelties, they also brought devastating consequences. European diseases, against which Indigenous populations had no immunity, swept through communities, decimating populations. Historians estimate that diseases like smallpox and measles reduced Indigenous populations by as much as 90% in some areas, leaving a void that would never fully heal.

Beyond disease, the burgeoning European presence brought escalating land disputes and cultural clashes. English and French colonial powers vied for control of the lucrative North American territories, dragging Indigenous nations into their conflicts. The Kennebec, strategically positioned between the two colonial powers, found themselves caught in a series of brutal wars, including King Philip’s War and the French and Indian Wars. Their primary village, Norridgewock, located near what is now Madison, Maine, became a flashpoint.

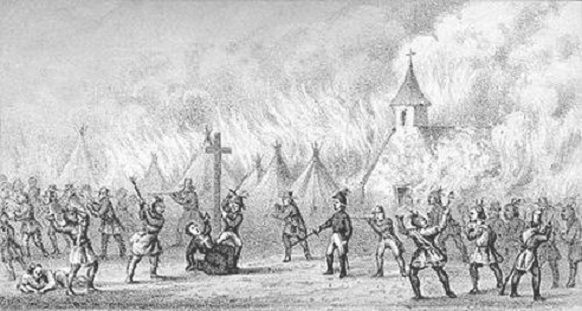

Norridgewock was not merely a village; it was a significant cultural and political center for the Kennebec, home to a prominent Jesuit mission led by Father Sébastien Rale (or Rasles). Rale, a controversial figure, was seen by the French as an ally and by the English as an agitator, fueling the Kennebec’s resistance to English encroachment. The village’s destruction in 1724 by a combined force of New England colonial militia and Mohawk warriors marked a turning point. Father Rale was killed, and the Kennebec people were dispersed, many seeking refuge with other Abenaki communities or migrating northward to Canada. This event was not just a military defeat; it was a profound cultural trauma, shattering the heart of their community and scattering their people.

"The destruction of Norridgewock wasn’t just a battle lost; it was a forced displacement, an attempt to erase our presence," states a community advocate. "But even then, our spirit endured. Our people carried their stories, their language, their knowledge in their hearts, even as they sought safety and rebuilt their lives elsewhere."

In the centuries that followed, the Kennebec people faced relentless pressure to assimilate. Their lands were steadily encroached upon by settlers, their language suppressed, and their traditional practices discouraged or outlawed. Without formal treaties that recognized their land rights (unlike some other Wabanaki nations), the Kennebec found themselves marginalized and dispossessed. Many descendants blended into the broader population, their Indigenous heritage often hidden or forgotten due to societal pressures and systemic racism.

This history of displacement and lack of formal treaties is a critical factor in their current status. While the Penobscot Nation, Passamaquoddy Tribe, Houlton Band of Maliseet Indians, and Aroostook Band of Micmacs all achieved federal recognition, establishing government-to-government relationships with the United States, the Kennebec, as a distinct tribal entity, did not. Federal recognition is not merely symbolic; it confers a host of rights, including sovereignty, access to federal programs for healthcare, education, housing, and economic development, and the ability to reclaim and manage ancestral lands. For the Kennebec, the absence of this recognition means a constant uphill battle to assert their identity and secure resources.

Despite these immense challenges, the spirit of the Kennebec people has never been extinguished. In recent decades, there has been a powerful resurgence of interest in reclaiming and revitalizing their heritage. Descendants of the Kennebec people, identifying as the Kennebec Nation or as part of the broader Abenaki community, are actively working to reconstruct their history, revitalize their language (a dialect of Eastern Abenaki), and educate the public about their enduring presence.

"We are still here," asserts a young Kennebec language learner, practicing ancient words. "Our language is our connection to our ancestors, to the land, to who we are. Every word we learn is an act of defiance against erasure, a step towards healing."

Community efforts often focus on land stewardship, advocating for the protection of sacred sites and ancestral territories along the Kennebec River. They work with environmental groups and state agencies to ensure that the river, once their economic and spiritual backbone, is preserved for future generations. Educational initiatives are crucial, aiming to correct historical inaccuracies and share the true story of the Kennebec with schools and the wider public. Cultural events, though often smaller and less formalized than those of federally recognized tribes, serve as vital gatherings for community members to share traditions, stories, and strengthen their collective identity.

The fight for formal recognition continues to be a central goal for many. It is a complex and arduous process, requiring extensive historical documentation and demonstrating continuous community existence since first contact. While the path to federal recognition is fraught with bureaucratic hurdles, the Kennebec people understand its profound importance for self-determination and the well-being of their future generations. They seek not just acknowledgement, but justice – a formal affirmation of their unbroken lineage and their inherent right to govern themselves and care for their ancestral lands.

The story of the Kennebec Nation is a compelling reminder that Indigenous identity is not monolithic, nor is it solely defined by federal government status. It is a story of a people who have faced the brunt of colonization, yet have managed to preserve their cultural heart against overwhelming odds. As the Kennebec River continues its timeless journey to the sea, so too does the Kennebec people’s journey continue – a journey of remembrance, resilience, and an unwavering hope that their voices will be fully heard, and their enduring presence finally recognized, in the Dawnland they have always called home. Their echoes resonate through the forests and along the riverbanks, a powerful testament to a spirit that refuses to be silenced.