Echoes of Thunder: Apache Pass and the Birth of a Legend

In the rugged, sun-baked landscape of Arizona, where the Chiricahua Mountains pierce the sky with jagged, formidable peaks, lies a narrow defile that once held the key to an empire: Apache Pass. More than just a geographical feature, this desolate stretch of land became the crucible where the fate of the American Southwest was forged in fire and blood. It was here, in the early 1860s, that a series of events – from a grave misunderstanding to a pitched battle – ignited decades of brutal conflict, creating legends and etching the name of a formidable Apache leader, Cochise, into the annals of American history.

The story of Apache Pass is not merely a chronicle of military engagements; it is a profound narrative of cultural clash, broken trust, and the desperate struggle for survival. It’s a tale that speaks to the very heart of the American frontier, where the promise of Manifest Destiny collided violently with the ancient claims of indigenous peoples.

A Crossroads of Empires and Cultures

For centuries, Apache Pass was a vital artery for the Chiricahua Apache, their ancestral lands stretching across what is now southeastern Arizona and southwestern New Mexico. The pass, with its precious springs – the only reliable water source for miles – was a natural stronghold and a strategic pathway through the otherwise impenetrable Chiricahua range. It was their sanctuary, their hunting ground, and their highway.

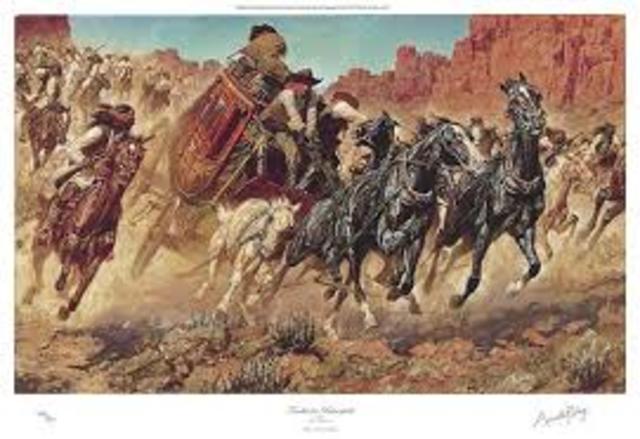

By the mid-19th century, however, this ancient world was rapidly encroached upon by the relentless westward expansion of the United States. The Butterfield Overland Mail Company established a stagecoach station at Apache Pass in 1858, a vital link in the transcontinental communication network. This brought a steady stream of American travelers, traders, and soldiers directly into the heart of Apache territory, creating an uneasy coexistence. For a time, a fragile peace prevailed, largely due to the efforts of powerful Apache leaders like Cochise, chief of the Chokonen band of Chiricahua Apache, and his father-in-law, the venerable Mangas Coloradas, chief of the Mimbres Apache. These were men of immense stature, both physically and politically, revered by their people and respected, if not fully understood, by the newcomers.

The Spark: The Bascom Affair (1861)

The delicate truce shattered in February 1861, in an incident that would become known as the Bascom Affair, a turning point that irrevocably altered the course of history in the Southwest. A young rancher named John Ward reported that his twelve-year-old stepson, Felix Telles, had been abducted by Apaches, along with some livestock, from his ranch near Sonoita Creek. Ward mistakenly believed Cochise was responsible.

Lieutenant George N. Bascom, a young, inexperienced officer fresh out of West Point, was dispatched with a small contingent of infantrymen to investigate. Bascom, armed with little understanding of Apache culture or diplomacy, and acting on an erroneous assumption, invited Cochise and several of his family members – including his brother, two nephews, and his wife and children – to a parley at the Butterfield station at Apache Pass.

Cochise, trusting the invitation, arrived unarmed and with his kin. Bascom immediately accused him of the kidnapping and demanded the return of the boy and the stolen property. Cochise vehemently denied involvement, explaining that his band was not responsible and offering to help find the true culprits, likely a different Apache group, the Coyotero. But Bascom, convinced of Cochise’s guilt, refused to listen. He ordered his soldiers to arrest Cochise and his party.

What followed was a moment of raw, desperate violence. Cochise, realizing the treachery, drew a knife, slashed his way through the canvas tent, and escaped into the mountains under a hail of gunfire. His relatives, however, remained captive. Enraged by the betrayal and the seizure of his family, Cochise immediately retaliated, capturing three Americans, including the Butterfield station agent, and demanded a prisoner exchange. Bascom refused.

The situation spiraled into a grim cycle of vengeance. Cochise killed his American captives, hanging them in full view of the station. Bascom, in turn, ordered the execution of six Apache prisoners he held – Cochise’s brother and two nephews among them – hanging them from mesquite trees. This act of cold-blooded retribution, fueled by misunderstanding and pride, was the ultimate betrayal.

"The Bascom Affair was the spark that ignited the long and bloody Apache Wars," historian Dan L. Thrapp would later write, capturing the profound impact of this incident. "Cochise, once a man who could be reasoned with, became a bitter enemy." From that day forward, Cochise waged an unrelenting war against the Americans, transforming from a reluctant peacemaker into one of the most feared and respected guerrilla leaders in American history. The fragile peace was shattered, replaced by a deep-seated hatred and a thirst for vengeance that would fuel conflict for decades.

The Civil War and the Battle for the Pass (1862)

The outbreak of the American Civil War in 1861 added another complex layer to the unfolding drama in Arizona. With Union troops withdrawn from the frontier to fight in the East, the territory became a lawless land, ripe for Confederate expansion. Texas Confederates, under Brigadier General Henry Hopkins Sibley, invaded New Mexico with ambitions of pushing further west to California, aiming to seize its gold and Pacific ports.

To counter this threat and reassert Union control, Brigadier General James H. Carleton organized the "California Column," a force of approximately 2,000 California Volunteers. Their mission was to march across the scorching deserts of Arizona, secure the territory, and push the Confederates out of New Mexico. Apache Pass, with its vital water supply, lay directly in their path, an unavoidable obstacle.

Cochise and Mangas Coloradas, recognizing the strategic importance of the pass, formed an alliance, assembling an estimated 500-700 Apache warriors – a formidable force for the time. They resolved to deny the Union troops access to the water, knowing that without it, the American advance would falter and die in the desert.

On July 15, 1862, a detachment of the California Column, led by Captain Thomas Roberts, comprising 126 men of the 1st California Infantry and a section of the 3rd U.S. Artillery with two powerful mountain howitzers, approached Apache Pass. As they entered the narrow canyon, they were met by a hail of arrows and gunfire from the Apaches, who had expertly positioned themselves on the rocky ridges overlooking the pass.

The Apaches, masters of guerrilla warfare, used the rugged terrain to their advantage, firing from concealed positions, making it difficult for the soldiers to pinpoint their locations. The fight quickly became a desperate struggle for survival for the Union troops, pinned down and exposed to constant fire. The Apaches fought with ferocity and determination, their war cries echoing through the canyon.

However, the tide of battle began to turn with the deployment of the Union artillery. The two mountain howitzers, small but potent cannons, were brought to bear. These weapons, capable of firing explosive shells, were something the Apaches had rarely, if ever, encountered in battle. The thundering roar of the cannons and the devastating impact of the shells, exploding among their positions on the ridges, had a profound psychological effect.

One account describes the impact: "The Apache warriors, accustomed to close-quarters combat and the rifle’s crack, were utterly bewildered by the exploding shells. They had no defense against such a weapon, and its terror spread through their ranks." The shells forced the Apaches to abandon their strategic high ground. Despite their bravery and superior knowledge of the terrain, they could not withstand the continuous bombardment. After several hours of intense fighting, the Apaches, suffering casualties and unable to dislodge the well-armed Americans, were forced to withdraw.

The Battle of Apache Pass, while a tactical victory for the Union, was not without cost. The Americans suffered several killed and wounded, and the encounter underscored the formidable resistance they would face. More importantly, it established a permanent U.S. military presence in the heart of Apache territory.

The Legacy of Apache Pass

Following the battle, the Union forces established Fort Bowie near the springs at Apache Pass. This fort, strategically placed, became a crucial outpost in the ensuing Apache Wars, a symbol of American resolve to control the territory. However, the battle did not break the spirit of Cochise. Instead, it hardened his resolve. For another decade, he led his Chiricahua warriors in a relentless campaign of raids and ambushes, proving himself a military genius who consistently outmaneuvered and outfought the U.S. Army.

Mangas Coloradas, the elder statesman of the Apache, would not live to see the end of the conflict. In 1863, he was lured into a peace parley under a flag of truce by American soldiers and was subsequently captured, tortured, and murdered while attempting to "escape." This further cemented Apache distrust and fueled Cochise’s determination.

Cochise, despite immense pressure and relentless pursuit, maintained his freedom and fought on until 1872, when he finally agreed to a peace treaty negotiated by General Oliver O. Howard. The terms secured a reservation for his people in their beloved Chiricahua Mountains, a testament to his unwavering leadership and the respect he had earned, even from his enemies. He died peacefully on that reservation in 1874, his legend firmly established.

Apache Pass, therefore, stands as more than just the site of a battle. It is a legendary landmark in American history, representing the point of no return in the Apache Wars. It embodies the tragic consequences of misunderstanding, the fierce struggle for land and survival, and the enduring power of leadership in the face of overwhelming odds. The echoes of thunder from those howitzers, the war cries of Cochise’s warriors, and the desperate struggles of soldiers still reverberate through the canyon.

The legend of Apache Pass is intertwined with the legend of Cochise himself – a figure of defiance, resilience, and unyielding spirit. It reminds us of the complex and often brutal birth of the American West, a history carved out of conflict, where courage and tragedy walked hand in hand, forever shaping the landscape and the narratives of a nation.