Echoes on the Bighorn: The Brief, Bloody Life of Fort C.F. Smith

In the stark, untamed expanse of what is now southeastern Montana, where the Bighorn River carves its path through a landscape of rugged bluffs and vast prairies, stand the faint, windswept remnants of a forgotten outpost. Fort C.F. Smith, established in 1866, was not destined for glory or long-term strategic importance. Instead, its brief, two-year existence serves as a poignant, blood-soaked testament to the brutal realities of westward expansion, the fierce resistance of Native American nations, and the ultimate futility of military might against an implacable will. It was a fort built on ambition, defended with desperation, and abandoned in defeat, leaving behind a legacy etched in the very soil it once claimed to control.

The story of Fort C.F. Smith is inextricably linked to the Bozeman Trail, a treacherous shortcut blazed in 1863 by John Bozeman and John Jacobs. This route, slicing directly through the prime hunting grounds of the Lakota Sioux, Cheyenne, and Arapaho, promised a quicker path to the Montana goldfields than the longer, safer Oregon Trail. For the thousands of hopeful prospectors and settlers streaming west, it represented opportunity; for the Indigenous peoples who had called this land home for millennia, it was an intolerable invasion. The U.S. government, eager to facilitate settlement and secure resources, chose to protect this contested artery with a series of forts. Fort C.F. Smith was the northernmost of these, strategically located near the mouth of the Bighorn Canyon, where the trail crossed the Bighorn River.

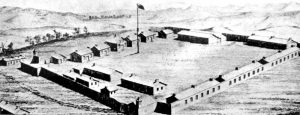

Built by Colonel Henry B. Carrington’s command in August 1866, the fort was named in honor of General Charles Ferguson Smith, a distinguished veteran of the Mexican-American War and an early casualty of the Civil War. Its construction was a grueling affair, undertaken in hostile territory under the constant threat of attack. Soldiers, already exhausted from the march, toiled to raise log palisades, barracks, and storehouses, using whatever local timber they could fell. The initial garrison consisted of elements of the 18th U.S. Infantry and later the 27th U.S. Infantry, a diverse group of veterans and raw recruits, many of whom quickly learned the harsh realities of frontier life.

From its very inception, Fort C.F. Smith was a beleaguered outpost. The Lakota war leader Red Cloud, a towering figure of resistance, had vehemently opposed the establishment of the Bozeman Trail forts during peace councils at Fort Laramie in 1866. When his demands for the abandonment of the trail were ignored, he walked out of the negotiations, declaring, "No white man shall travel this road." This was not an empty threat. Red Cloud’s War, as it became known, was a meticulously planned and fiercely executed campaign to drive the interlopers from the Powder River Country.

Fort C.F. Smith, along with its sister forts, Phil Kearny and Reno, became targets in a relentless war of attrition. The soldiers and civilians stationed there lived under a state of perpetual siege. Supply trains were routinely ambushed, wood-cutting parties were attacked, and even men venturing short distances from the fort risked their lives. The constant threat wore down morale, and the isolation was profound. "We are here in the very heart of the enemy’s country," wrote one soldier, "and every day is a battle."

The attacks were not merely skirmishes; they were often large-scale, coordinated assaults. One of the most famous and harrowing incidents associated with Fort C.F. Smith was the "Hayfield Fight" on August 1, 1867. A detail of 20 soldiers and six civilians, led by Lieutenant Sigismund Sternberg, was harvesting hay in a field about three miles from the fort when they were ambushed by an estimated 500-800 Lakota and Cheyenne warriors. The small group quickly formed a defensive perimeter around their wagons and a small corral.

What followed was a desperate fight for survival. For hours, the vastly outnumbered men held off wave after wave of attacks. They were armed with new Springfield Model 1866 "Trapdoor" rifles and, crucially, a few Spencer repeating rifles, which provided a significant advantage in sustained firepower. The Native warriors, accustomed to the single-shot muzzleloaders of their enemies, were astonished and frustrated by the rapid rate of fire. As the historian Robert M. Utley noted, "The Spencer carbine was the instrument that spelled the difference between victory and defeat for the beleaguered whites."

Despite the overwhelming odds, the defenders managed to hold their ground, inflicting heavy casualties on their attackers. Lieutenant Sternberg was killed early in the fight, but the remaining men fought on with grim determination. They were eventually relieved by a cavalry detachment from the fort, whose arrival forced the warriors to withdraw. The Hayfield Fight was a testament to the bravery of the soldiers and civilians, but it also underscored the extreme danger and the sheer numerical superiority of the Native forces. It was a small victory in a larger war that the Americans were clearly losing.

Interestingly, Fort C.F. Smith also saw the complex dynamics of inter-tribal relations play out. While the Lakota, Cheyenne, and Arapaho were united in their opposition to the forts, the Crow Nation, whose traditional lands encompassed the Bighorn River area, often allied with the U.S. Army. The Crow saw the Lakota expansion as a threat to their own territory and livelihoods, and they frequently served as scouts and allies for the soldiers, providing invaluable intelligence and sometimes fighting alongside them. This alliance, born of shared enmity towards the Lakota, highlights the nuanced and often shifting political landscape of the American West.

Life at Fort C.F. Smith was a monotonous cycle of fear, vigilance, and hardship. Supplies were scarce, often delayed or destroyed by attacks. Food was basic and repetitive, and diseases like scurvy and dysentery were common. The bitter Montana winters were brutal, with deep snows and sub-zero temperatures adding another layer of misery. Communication with the outside world was minimal, leaving the garrison feeling utterly isolated and forgotten. The psychological toll of constant readiness for battle, combined with the extreme living conditions, led to widespread desertion and low morale.

The strategic value of the Bozeman Trail forts, always questionable, began to wane as the government reassessed its priorities. Red Cloud’s War had proven incredibly costly in both lives and resources, and the prospect of a transcontinental railroad further south offered a more secure and economically viable route to the West. Public opinion back East was turning against what was increasingly seen as an expensive and bloody frontier war.

Ultimately, it was diplomacy, spurred by military failure, that brought about the end of Fort C.F. Smith. The Treaty of Fort Laramie in 1868, negotiated between the U.S. government and various Lakota, Cheyenne, and Arapaho bands, stipulated that the United States would abandon the Bozeman Trail and its forts in exchange for peace and the establishment of the Great Sioux Reservation. For Red Cloud and his allies, it was a resounding victory – one of the few instances in American history where the U.S. government acceded to Native American demands following a military defeat.

In July 1868, the order came down: Fort C.F. Smith was to be abandoned. The remaining garrison packed what they could, and the soldiers marched away, leaving behind the structures they had so arduously built and fiercely defended. They did not destroy the fort themselves; instead, they left it to their adversaries. Almost immediately after the last troops departed, Lakota warriors descended upon the fort. In a symbolic act of reclamation and vengeance, they systematically dismantled and burned every building, leaving nothing but charred timbers and the faint outline of the fort’s foundations. The message was clear: this land belonged to them, and no white man’s fort would stand upon it.

Today, the site of Fort C.F. Smith is managed by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) and is part of the Bighorn Canyon National Recreation Area. While no original structures remain, the outlines of the fort’s walls and some building foundations are visible, marked by interpretive signs that tell the fort’s story. Visitors can walk the grounds, imagining the daily struggles of the soldiers and the fierce determination of the warriors who fought over this contested ground.

Fort C.F. Smith stands as a poignant symbol of a pivotal moment in American history. It represents the collision of two vastly different cultures, the unyielding drive of American expansionism, and the desperate struggle of Indigenous peoples to defend their homelands and way of life. Its brief, bloody life underscores the immense human cost of conquest and resistance. The winds that sweep across the Bighorn still carry whispers of the past – of courage and fear, of life and death, and of a fort that, despite its fleeting existence, left an indelible mark on the tapestry of the American West. It reminds us that history is not just about victories, but also about the bitter lessons learned in the crucible of conflict, and the enduring power of a landscape to hold the echoes of those who fought and died upon it.