Echoes on the Kennebec: The Enduring Spirit of the Arosaguntacook

Along the winding, ancient waters of the Kennebec River in what is now central Maine, a people once thrived, their lives intricately woven into the rhythm of the seasons and the bounty of the land. They were the Arosaguntacook, a name believed to mean "people of the rocky/tidal river" or "where the current is rough," a testament to their deep connection to this vibrant waterway. As a crucial member of the powerful Wabanaki Confederacy – the "People of the Dawnland" – the Arosaguntacook were guardians of a rich cultural heritage, skilled navigators, astute traders, and formidable defenders of their ancestral territory. Their story, often overshadowed by the broader narratives of colonial expansion, is one of profound resilience, devastating loss, and an enduring spirit that echoes through the generations, a testament to the strength of Indigenous identity.

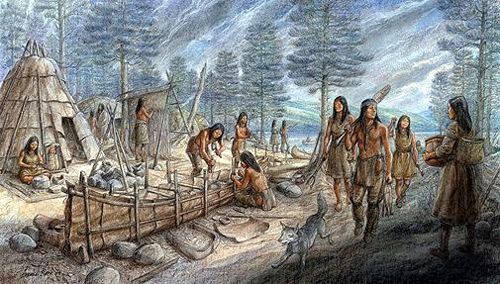

Before the arrival of European ships on the shores of the Dawnland, the Arosaguntacook enjoyed a sophisticated and sustainable way of life that had evolved over millennia. Their territory stretched from the Kennebec River’s estuary deep into its interior, encompassing a diverse landscape of forests, lakes, and coastal areas. They practiced a seasonal migration pattern, moving inland to hunt moose, deer, and bear in the winter, and returning to the coast in spring and summer to fish for salmon, sturgeon, and eel, gather shellfish, and cultivate corn, beans, and squash in fertile riverine plots. Their birchbark canoes, marvels of Indigenous engineering, allowed them to navigate the intricate network of rivers and lakes, connecting them to other Wabanaki communities and facilitating extensive trade networks stretching across the Northeast.

Their society was organized around kinship, with strong communal ties and a deep respect for elders and the natural world. Oral traditions, passed down through generations, conveyed their history, spiritual beliefs, and moral codes. Central to their worldview was the concept of kinship with all life, viewing animals, plants, and the land itself as relatives to be honored and respected. This holistic understanding fostered a sustainable relationship with their environment, ensuring that resources were never depleted, a stark contrast to the extractive mindset that would soon arrive from across the Atlantic.

The 17th century brought a seismic shift to the Dawnland. European explorers, fishermen, and eventually settlers began to frequent the coast, eager to exploit the region’s abundant resources, particularly the lucrative fur trade. The Arosaguntacook, like other Wabanaki groups, initially engaged in trade, exchanging beaver pelts and other furs for European goods such as metal tools, cloth, and firearms. While these new technologies initially offered advantages, they also introduced unforeseen and devastating consequences. European diseases, against which Indigenous peoples had no immunity, swept through communities like wildfire. Historians estimate that epidemics of smallpox, measles, and influenza decimated populations, sometimes by as much as 90%, within a few generations of contact. This demographic catastrophe profoundly weakened the Arosaguntacook, disrupting their social structures and undermining their ability to resist the encroaching colonial powers.

As the 17th century gave way to the 18th, the Arosaguntacook found themselves caught in the escalating geopolitical struggle between France and England for control of North America. Maine, situated on the contested frontier, became a frequent battleground. The Arosaguntacook, along with other Wabanaki tribes, generally allied with the French, who, unlike the English, were more interested in trade and conversion than outright land acquisition. This alliance, however, plunged them into a series of brutal conflicts known collectively as the "Dawnland Wars," including King William’s War, Queen Anne’s War, and Father Rale’s War (also known as Dummer’s War).

One of the most tragic episodes in Arosaguntacook history occurred during Father Rale’s War. Norridgewock, a prominent Arosaguntacook village on the Kennebec, was a thriving center of Indigenous life and French missionary activity, largely due to the presence of the Jesuit priest Sébastien Rale. The village served as a symbol of Wabanaki resistance and French influence. In August 1724, a force of New England militia attacked Norridgewock, massacring many of its inhabitants, including Father Rale, and burning the village to the ground. This devastating event not only marked a severe blow to the Arosaguntacook but also signaled the increasing ferocity of the colonial expansion and the diminishing prospects for Indigenous sovereignty in their ancestral lands.

The relentless pressure from colonial settlement, coupled with continuous warfare and disease, forced many Arosaguntacook to abandon their traditional territories. Some sought refuge among other Wabanaki communities that still maintained a foothold in Maine, like the Penobscot. However, a significant number migrated north to French Canada, particularly to the mission village of Odanak (St. Francis) on the St. Francis River in Quebec. There, they joined other Abenaki and Wabanaki refugees, forming a vibrant, multi-tribal community that maintained cultural and linguistic ties while adapting to new circumstances. This dispersal, while a tragedy of displacement, also became a strategy for survival, ensuring the continuation of their people, albeit in new configurations.

Despite the profound disruptions, the spirit of the Arosaguntacook persisted. Their language, a dialect of Eastern Abenaki, continued to be spoken, though increasingly threatened. Oral histories and traditional knowledge were carefully guarded and passed down. The skills of basket-making, often using ash and sweetgrass, and the intricate art of storytelling remained vital ways of preserving cultural identity. The memory of the Kennebec, of Norridgewock, and of their ancestral lands, remained etched in the collective consciousness of their descendants.

In the modern era, the Arosaguntacook, as a distinct, federally recognized tribal entity in the United States, is largely considered to have been absorbed into other Wabanaki groups or to have migrated. Their descendants are now integral parts of the broader Wabanaki Confederacy in Maine – including the Penobscot Nation, Passamaquoddy Tribe, Maliseet, and Mi’kmaq – and the Abenaki communities in Quebec, particularly Odanak. These communities carry forward the legacy of the Arosaguntacook, fighting for self-determination, land rights, and cultural revitalization.

The struggle for recognition and the reclaiming of identity are central to the modern Wabanaki experience. Language revitalization programs are underway, aiming to breathe new life into the Abenaki language, often through immersion schools and community classes. Cultural centers preserve artifacts, host traditional ceremonies, and educate younger generations about their heritage. Environmental stewardship remains a paramount concern, as descendants work to protect the very rivers and forests that sustained their ancestors, recognizing the profound spiritual and physical connection to the land.

The story of the Arosaguntacook is not merely a chapter in history; it is a living narrative. It serves as a powerful reminder of the devastating impact of colonization, the resilience of Indigenous peoples, and the enduring importance of cultural heritage. While the physical village of Norridgewock may lie in ruins, and the distinct political entity of the Arosaguntacook may have been dissolved by centuries of conflict and displacement, their spirit flows as surely as the Kennebec River itself. Their descendants, whether in Maine or Quebec, are the inheritors of a proud lineage, carrying forward the wisdom, the language, and the unbreakable spirit of the People of the Rocky River, ensuring that the echoes on the Kennebec will never truly fade. Their history is a call to acknowledge the past, understand the present, and support the future of Indigenous sovereignty and cultural flourishing in the Dawnland.