Echoes on the Prairie Winds: The Enduring Legends of Kansas’s Indian Battles

Kansas, a name synonymous with the vast, undulating plains, the heartland of America, and the iconic imagery of prairie schooners pushing westward, holds a history etched deep with both promise and profound tragedy. Beneath the golden wheat fields and the serene horizon lies a landscape once vibrant with the thunder of buffalo hooves and the ancient cultures of indigenous peoples. This was a land that became the crucible of one of America’s most defining and devastating conflicts: the Indian Wars. The legends born from these Kansas Indian battles are not always tales of glory, but often somber echoes of resistance, displacement, and a clash of civilizations that irrevocably shaped the nation.

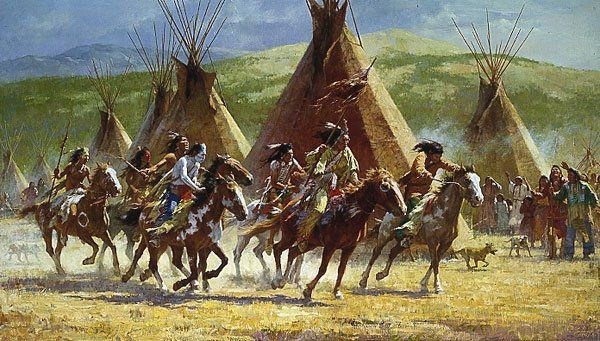

Before the deluge of westward expansion, Kansas was a dynamic tapestry of tribal territories. The Kansa (Kaw) people, the very namesake of the state, lived along the Kansas River. To the north, the Pawnee held sway, while the Wichita lived further south. But it was the powerful nomadic tribes of the Great Plains – the Cheyenne, Arapaho, Comanche, and Kiowa – who roamed the western reaches, following the immense buffalo herds that were the bedrock of their existence. These tribes, each with distinct cultures, languages, and intricate social structures, had navigated the complexities of inter-tribal relations for centuries, their lives intrinsically linked to the land and its resources.

The mid-19th century brought an unstoppable tide of change. The concept of "Manifest Destiny" fueled a relentless push across the continent. Gold rushes in California and Colorado, the promise of free land, and the construction of transcontinental railroads transformed the trickle of pioneers into a flood. Kansas, positioned as a vital corridor for trails like the Oregon and Santa Fe, became a literal crossroads where two vastly different worlds collided. For the new arrivals, the land was "empty" and ripe for "improvement"; for the indigenous inhabitants, it was home, a sacred inheritance.

This fundamental misunderstanding, coupled with a rapacious hunger for land and resources, inevitably led to conflict. Treaties, often signed under duress and rarely honored by the U.S. government, became scraps of paper. The buffalo, essential for the Plains tribes’ survival, became targets for commercial hunters and a strategic tool for the U.S. Army, famously articulated by General Philip Sheridan: "Kill all the buffalo you can! Every buffalo dead is an Indian gone." This systematic destruction aimed to starve the tribes into submission, a grim tactic that epitomized the brutal nature of the impending wars.

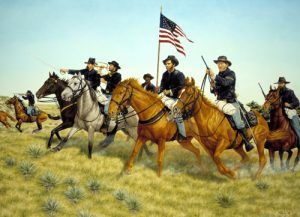

The U.S. Army, with its cavalry regiments, became the primary instrument of federal policy on the plains. Figures like General George Armstrong Custer, Colonel George A. Forsyth, and many lesser-known soldiers found themselves embroiled in a war unlike any they had previously fought. Facing them were formidable warriors such as Roman Nose of the Cheyenne, Tall Bull, and numerous other chiefs and headmen who, despite being outmatched in weaponry and numbers, fought with a fierce determination to protect their people and their way of life.

One of the most legendary and harrowing engagements in Kansas occurred in September 1868: the Battle of Beecher Island. A small detachment of 50 U.S. Army scouts, led by Colonel George A. Forsyth, were ambushed by a much larger force of Cheyenne, Arapaho, and Sioux warriors, estimated to be between 600 and 1,000 strong. The scouts, finding themselves surrounded, quickly entrenched themselves on a small sand island in the Arikaree Fork of the Republican River, now within present-day Yuma County, Colorado, but deeply tied to the Kansas theatre of operations.

The siege lasted for nine days. Under constant fire, with dwindling supplies and no hope of immediate relief, the scouts faced overwhelming odds. Forsyth himself was wounded multiple times, and his second-in-command, Lieutenant Fred Beecher, was killed early in the fight. The warriors, led by the charismatic Cheyenne war chief Roman Nose, launched repeated charges, but the entrenched scouts, armed with new Spencer repeating rifles, held their ground. A critical turning point came when Roman Nose, a figure revered for his spiritual power and bravery, was killed during one of these charges. His death was a significant blow to the morale of the allied tribes.

Two scouts, "Dirty" Dave Day and Jack Stilwell, famously volunteered to sneak through enemy lines to seek help, a perilous journey that took them over 100 miles. Their daring act, and the sheer tenacity of the besieged scouts, became a testament to the brutal resolve on both sides. When relief finally arrived, only a handful of the original 50 scouts were still able to fight. The Battle of Beecher Island, though a tactical victory for the U.S. Army, was a stark illustration of the ferocity and determination of the Plains tribes in defending their lands. It became a powerful legend, celebrated in dime novels and later in films, cementing the image of the brave frontier scout against overwhelming odds, while often overlooking the desperation and courage of the Native warriors.

Another significant engagement, often linked to the Kansas Indian Wars, was the Battle of Summit Springs in July 1869. This time, General Custer and his 7th U.S. Cavalry played a central role. Following a series of raids by Cheyenne Dog Soldiers (a fierce warrior society) in Kansas and Colorado, Custer pursued the group, led by Tall Bull, into present-day Colorado, near the Kansas border. Custer’s troops launched a surprise attack on the Dog Soldier encampment, scattering the warriors and killing Tall Bull. This decisive strike effectively broke the back of the Dog Soldier resistance, further diminishing the ability of the tribes to wage organized warfare. The ruthlessness of these campaigns, often targeting non-combatants and destroying camps, was a hallmark of the "total war" strategy employed by the U.S. Army to end the "Indian problem."

While the grand narratives often focus on the powerful nomadic tribes, the experience of the sedentary Kansa (Kaw) people, the state’s namesake, provides a poignant counterpoint. Their story is one of gradual, relentless dispossession rather than dramatic battles. Living in permanent villages and engaging in agriculture, the Kansa were initially more receptive to American settlement. However, their lands were systematically whittled away through a series of treaties, each one pushing them further to the margins. Their population, ravaged by disease and cultural disruption, dwindled.

One almost forgotten "battle" for the Kansa was the Battle of theaps in 1860, near present-day Council Grove. It wasn’t a clash with the U.S. Army, but a desperate skirmish between the Kansa and a raiding party of Cheyenne and Arapaho warriors. While minor in scale compared to Beecher Island, it symbolized the Kansa’s increasingly precarious position – caught between the encroaching white settlers and the more powerful Plains tribes, who viewed their lands as fair game. This internal conflict further weakened their ability to resist the ultimate fate of removal. By 1873, the Kansa were forcibly removed from their last remaining lands in Kansas to a reservation in Indian Territory (Oklahoma), a tragic end to their long history in the land that bore their name.

The legends of Kansas’s Indian battles are complex and often contradictory. For some, they evoke tales of frontier heroism and the triumph of American expansion. For others, they are deeply painful memories of injustice, cultural annihilation, and the brutal reality of conquest. The "Indian Wars" were not always pitched battles between equal forces; they often involved massacres of villages, the targeting of women and children, and the systematic destruction of the very environment that sustained Native life. The infamous Sand Creek Massacre in Colorado (1864), though not in Kansas, cast a long, dark shadow over the entire region, exemplifying the savagery that could be unleashed upon Native populations, even those seeking peace.

The aftermath of these conflicts was devastating. By the 1880s, the vast buffalo herds were gone, reduced from tens of millions to a few hundred. The nomadic way of life, inextricably linked to the buffalo, was utterly destroyed. The remaining tribes were confined to reservations, their cultures suppressed, their languages discouraged, and their children sent to boarding schools designed to "kill the Indian to save the man." The wide-open plains of Kansas, once a land of freedom and abundance for its indigenous peoples, were transformed into agricultural fields and fenced-in ranches.

Today, the echoes of these battles still resonate across Kansas. Historical markers dot the landscape, commemorating skirmishes and forgotten villages. Museums and cultural centers strive to tell a more complete, nuanced story, incorporating Native American perspectives that were long silenced. The descendants of the Cheyenne, Arapaho, Pawnee, Kansa, and other tribes, though dispersed, carry forward the legacy of their ancestors – a legacy of resilience, survival, and a profound spiritual connection to the land.

The legends of Kansas’s Indian battles are not merely historical footnotes; they are cautionary tales embedded in the American psyche. They remind us of the immense human cost of expansion, the tragic consequences of broken promises, and the enduring power of resistance. As the prairie winds whisper across the Kansas plains, they carry not only the rustle of wheat but also the faint, poignant echoes of a bygone era, reminding us that true understanding of America’s past requires confronting its complexities, its triumphs, and its profound sorrows.