The Unhealed Scar: America’s Forced Relocation of Native American Tribes

The echoes of a dark chapter in American history reverberate through the present, a period when the burgeoning nation, fueled by expansionist dreams and an insatiable hunger for land, committed one of its most profound injustices: the forced relocation of Native American tribes. This wasn’t merely a series of isolated incidents, but a systemic, government-sanctioned policy that uprooted entire civilizations, leaving behind a legacy of trauma, dispossession, and a wound that, for many, remains unhealed.

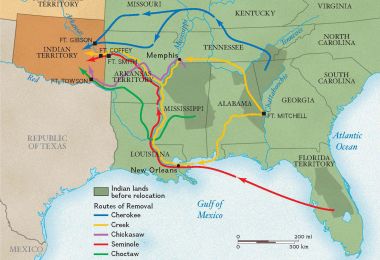

The most infamous of these expulsions is often encapsulated by the "Trail of Tears," yet it was part of a broader, more brutal campaign that affected countless tribes across the burgeoning American frontier. From the Choctaw and Chickasaw to the Creek and Seminole, and most famously the Cherokee, the story is one of broken treaties, legal battles, military coercion, and unimaginable suffering.

The Seeds of Dispossession: A Nation’s Greed

From the earliest days of European settlement, the relationship between colonizers and Indigenous peoples was fraught with conflict over land. As the United States gained independence and began its westward expansion in the early 19th century, the pressure on Native American lands intensified dramatically. The concept of "Manifest Destiny"—the belief in America’s divinely ordained right to expand across the continent—provided a powerful ideological justification for dispossessing Indigenous populations.

The fertile lands of the Southeast, particularly desirable for the burgeoning cotton industry, and the discovery of gold in Cherokee territory in Georgia in 1828, turned desire into a feverish demand. Despite their long-standing occupation and sophisticated societies, Native American tribes were increasingly viewed not as sovereign nations, but as obstacles to "progress" and a source of valuable resources.

Many of these tribes, particularly the Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seminole (collectively known as the "Five Civilized Tribes" by white settlers due to their adoption of many Euro-American customs like written languages, constitutional governments, farming techniques, and even chattel slavery), had made significant efforts to assimilate. They built towns, established schools, developed written languages, and even published newspapers. The Cherokee Nation, for instance, had a written constitution modeled on the U.S. Constitution and a bicameral legislature. Yet, these efforts did not protect them.

The Legal Weapon: The Indian Removal Act of 1830

The legal framework for this mass expulsion was cemented by the Indian Removal Act of 1830. Championed by President Andrew Jackson, a veteran of wars against Native Americans and a staunch advocate for their removal, the Act authorized the president to negotiate treaties to exchange Native American lands in the east for lands west of the Mississippi River. While ostensibly voluntary, the power imbalance and implied threat of force made these "negotiations" anything but.

Jackson’s rhetoric often framed removal as a benevolent act, protecting Native Americans from the corrupting influence of white society and allowing them to preserve their cultures in the West. In his 1830 annual message to Congress, Jackson argued: "It will separate the Indians from immediate contact with settlements of whites; free them from the power of the States; enable them to pursue happiness in their own way and under their own rude institutions; will retard the progress of decay, which is lessening their numbers, and perhaps cause them gradually, under the protection of the Government and through the influence of good counsels, to cast off their savage habits and become an interesting, civilized, and Christian community."

This paternalistic veneer thinly veiled the land hunger that truly drove the policy. Jackson’s vision was clear: white expansion would not be impeded by Native American sovereignty.

A Battle in the Courts: Broken Promises and Defiant Power

The Cherokee Nation, unlike many other tribes, chose to fight their removal through the American legal system. They appealed to the Supreme Court, arguing that Georgia had no right to seize their land.

In Cherokee Nation v. Georgia (1831), Chief Justice John Marshall, while acknowledging the Cherokee as a "distinct political society," ruled that they were a "domestic dependent nation" rather than a foreign state, and thus lacked the standing to sue in the Supreme Court. However, in a subsequent case, Worcester v. Georgia (1832), Marshall delivered a landmark ruling that affirmed the Cherokee Nation’s sovereignty and declared Georgia’s laws concerning Cherokee land unconstitutional. Marshall stated that Georgia had no jurisdiction over the Cherokee territory and that the Cherokee Nation was a "distinct community, occupying its own territory, with boundaries accurately described, in which the laws of Georgia can have no force."

This was a clear victory for the Cherokee. But President Jackson famously defied the ruling, reportedly saying, "John Marshall has made his decision; now let him enforce it." Without presidential enforcement, the Supreme Court’s decision was rendered effectively meaningless. Georgia continued its encroachment, and the stage was set for forced removal.

The Treaty of New Echota: A Betrayal

Further complicating the Cherokee situation was the Treaty of New Echota, signed in 1835. This treaty was negotiated by a minority faction of the Cherokee Nation, known as the "Treaty Party" (led by Major Ridge, Elias Boudinot, and Stand Watie), who believed that resistance was futile and that the best course of action was to secure favorable terms for removal. However, the vast majority of the Cherokee Nation, led by Principal Chief John Ross, vehemently opposed the treaty, arguing that the Treaty Party had no authority to sign on behalf of the nation. Despite widespread Cherokee protests, including a petition signed by thousands, the U.S. Senate ratified the treaty by a single vote. It stipulated that the Cherokee would exchange their lands for territory in Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma) and receive five million dollars. The deadline for voluntary removal was set for May 1838.

The Trail of Tears: A Brutal Reality

When the deadline arrived, most Cherokees had not moved. President Martin Van Buren, Jackson’s successor, ordered General Winfield Scott to enforce the removal. Beginning in May 1838, some 7,000 U.S. soldiers, along with state militias, began forcibly rounding up an estimated 16,000 Cherokees from their homes in Georgia, Tennessee, North Carolina, and Alabama.

Families were rousted from their homes at bayonet point, often with little to no time to gather their belongings. They were confined in stockades, enduring disease, hunger, and unsanitary conditions, before being forced to march westward. The journey covered over 1,000 miles, much of it on foot, through the harsh winter of 1838-1839.

Eyewitness accounts paint a harrowing picture. Lieutenant John G. Burnett, a soldier who participated in the removal, later recalled: "I saw the helpless Cherokees arrested and dragged from their homes, and driven at the point of a bayonet into the stockades. And in the chill of a drizzling rain on an October morning I saw them loaded like cattle or sheep into six hundred and forty-five wagons and started toward the west." He described the suffering: "The trail of the exiles was a trail of death. They had to sleep in the open air, in the rain, snow and ice, on the frozen ground, and were forced to eat from wagons and drink from stagnant pools."

The conditions were abysmal: inadequate food, contaminated water, lack of shelter, and the rapid spread of diseases like cholera, dysentery, and smallpox. It is estimated that over 4,000 of the 16,000 Cherokees died during the forced march, a quarter of their population. The Cherokee called this journey "Nunna daul Isunyi," meaning "the trail where they cried."

While the Cherokee’s story is the most widely known, they were not alone. The Choctaw were the first to be removed in 1831, experiencing similar horrors. Around 2,500 of the 17,000 Choctaw died during their winter journey. The Creek Nation lost 3,500 of 15,000 during their removal. The Chickasaw, who negotiated better terms, managed to avoid some of the extreme suffering, but still faced immense challenges. The Seminole in Florida fiercely resisted removal, leading to the costly and protracted Second Seminole War (1835-1842), one of the longest and most expensive wars in U.S. history against Native Americans.

The Enduring Scar: A Legacy of Trauma and Resilience

The forced relocations had devastating and long-lasting consequences. Beyond the immediate loss of life, the removal shattered Indigenous communities, disrupted their social structures, destroyed their traditional economies, and severed their deep spiritual connections to their ancestral lands. The lands they were forced into were often unfamiliar, less fertile, and sometimes already inhabited by other tribes, leading to new conflicts.

The generational trauma stemming from these events continues to affect Native American communities today. It manifests in various forms, including higher rates of poverty, health disparities, and mental health challenges. The loss of language and cultural practices, though resiliently preserved by many, was also a profound consequence.

However, the story is not solely one of victimhood. It is also a testament to the incredible resilience and adaptability of Native American peoples. Despite immense suffering and deliberate attempts at cultural annihilation, Indigenous nations survived. They rebuilt their communities in Indian Territory, established new governments, and continued to fight for their rights and sovereignty.

Lessons Unlearned, Lessons Relearned

The forced relocation of Native American tribes stands as a stark reminder of the dangers of unchecked power, racial prejudice, and the pursuit of progress at any human cost. It challenges the romanticized narrative of American expansion and forces a reckoning with the nation’s foundational injustices.

Today, there is a growing movement towards acknowledging this dark past, promoting reconciliation, and supporting Native American sovereignty and self-determination. Museums, educational initiatives, and ongoing land rights movements strive to ensure that the stories of those who suffered on the Trail of Tears and countless other forced removals are never forgotten.

As we look to the future, the unhealed scar of forced relocation serves as a powerful cautionary tale. It underscores the importance of honoring treaties, respecting Indigenous rights, and fostering a society where the dignity and sovereignty of all peoples are truly recognized and upheld. Only by confronting the full truth of our history can we hope to build a more just and equitable future.