Forging the Union: The Enduring Saga of Admitting New States to the American Republic

From a nascent republic clinging to the Atlantic seaboard, the United States has grown into a continental power, a "more perfect Union" shaped significantly by the continuous, often contentious, process of admitting new states. Each star added to the national flag represents not just a new patch of land, but a unique chapter in American history, reflecting shifting demographics, political struggles, economic aspirations, and the enduring vision of a united nation. The journey of a territory to statehood is a complex interplay of constitutional mandate, political will, and the democratic aspirations of its people, a saga that continues to this day.

The Constitutional Cornerstone

The foundational authority for adding new states is remarkably brief, enshrined in Article IV, Section 3, Clause 1 of the U.S. Constitution: "New States may be admitted by the Congress into this Union; but no new State shall be formed or erected within the Jurisdiction of any other State; nor any State be formed by the Junction of two or more States, or Parts of States, without the Consent of the Legislatures of the States concerned as well as of the Congress."

This concise provision, however, belies the intricate and often fraught political process it has historically unleashed. The Founders understood that the young nation would expand, but they left the precise mechanisms to future generations, allowing for flexibility and, inevitably, intense debate. The primary hurdle has always been Congressional approval, a simple majority vote in both the House and Senate, followed by the President’s signature. Yet, behind this seemingly straightforward legislative act lies a rich tapestry of historical precedent, political maneuvering, and societal transformation.

The Unfolding Process: From Territory to State

While not explicitly detailed in the Constitution, a customary process for state admission has evolved over two centuries. The journey typically begins with a territory petitioning Congress for statehood. If Congress deems the territory ready, it often passes an "enabling act," which authorizes the territory to draft a state constitution. This constitution must be republican in form and generally align with the principles of the U.S. Constitution.

Once the territorial convention drafts and approves the constitution, it is then put to a vote by the territory’s residents. If ratified, the proposed constitution is submitted to Congress for approval. Upon Congressional consent and the President’s signature, the territory officially becomes a state, its representatives and senators taking their seats in the federal legislature. This seemingly orderly sequence has, at various points in history, been anything but.

A Nation Forged in Expansion: Historical Milestones

The first state admitted after the original thirteen was Vermont in 1791, followed quickly by Kentucky (1792) and Tennessee (1796). These early admissions were relatively smooth, emerging from existing colonial claims and westward migration. However, the Louisiana Purchase in 1803 dramatically altered the landscape, nearly doubling the nation’s size overnight and setting the stage for a century of westward expansion and, crucially, intense sectional conflict.

The most profound and often violent debates over statehood revolved around the issue of slavery. As the nation expanded, the balance of power in the Senate—where each state, regardless of population, received two votes—became paramount. The admission of Missouri in 1821, for instance, nearly fractured the young republic, sparking the infamous Missouri Compromise. This delicate legislative act balanced the entry of Missouri as a slave state with Maine as a free state, temporarily defusing tensions and establishing a geographical line for future slave state expansion. The compromise, though fragile, underscored how new state admissions had become a proxy battleground for national ideological divides.

The Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, which allowed residents of those territories to decide on slavery through "popular sovereignty," ignited further violence and effectively repealed the Missouri Compromise. The bloody "Bleeding Kansas" period demonstrated the dire consequences of unresolved statehood questions. The Civil War itself, in part, erupted over these very issues, leading to the unique case of West Virginia. Formed in 1863 from counties that seceded from Confederate Virginia, its admission was a controversial move, justified by the Union as an act of internal self-determination, but seen by Virginia as unconstitutional.

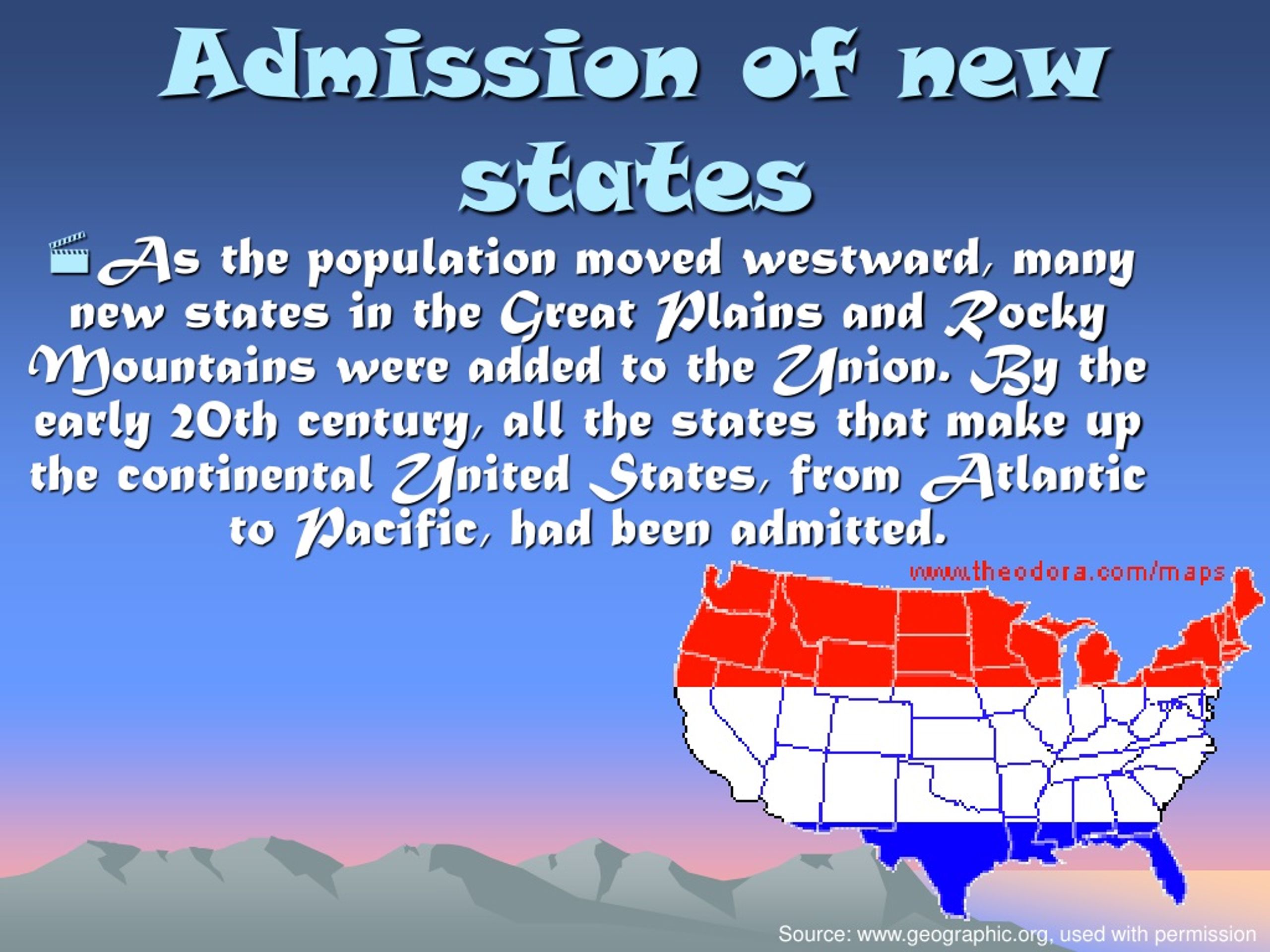

The post-Civil War era saw a flurry of admissions, particularly in the West, driven by the Homestead Act, railroad expansion, and the "Manifest Destiny" ethos. From Colorado in 1876 to Wyoming and Idaho in 1890, and Utah in 1896 (after finally renouncing polygamy), the map of the contiguous United States rapidly filled in.

The 20th century saw fewer additions, with Oklahoma (1907), Arizona (1912), and New Mexico (1912) completing the contiguous 48 states. The final two states to join the Union were Alaska and Hawaii in 1959. Their admission marked a significant departure, as they were non-contiguous territories, with distinct cultures and geographies. The debates surrounding their statehood touched on issues of distance, strategic importance during the Cold War, and concerns about their non-European populations, particularly in Hawaii. Their inclusion underscored the evolving nature of the American identity – a nation that could embrace diverse peoples and distant lands.

The Crucible of Contention: Challenges and Debates

Beyond the grand historical narratives, the admission of new states has always been fraught with specific challenges:

- Political Balance: Perhaps the most enduring challenge has been the impact on the balance of power in Congress, particularly the Senate. Every new state adds two senators, potentially shifting the legislative agenda and electoral outcomes for decades. This has been a primary driver of resistance to statehood for territories perceived as leaning towards one political party.

- Economic Viability: Congress has historically scrutinized a territory’s economic self-sufficiency. Could it sustain itself without undue federal aid? Did it have a stable tax base and sufficient population to justify the full rights and responsibilities of statehood?

- Population and Preparedness: While there’s no strict population requirement, a territory needs a sufficient populace to support a functioning state government and provide a viable tax base. Furthermore, the territory must demonstrate a capacity for self-governance, often through a history of elected territorial legislatures and adherence to democratic principles.

- Cultural and Social Integration: In some cases, cultural differences or unique social practices have been points of contention. Utah’s admission, for example, was delayed for decades due to the practice of polygamy by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Similarly, concerns about native populations and their integration have played roles in the debates over Western states and Hawaii.

Modern Day Debates: The Unfinished Map

Today, the debate over new state admissions primarily centers on two long-standing U.S. territories: Washington D.C. and Puerto Rico.

Washington D.C. Statehood: The District of Columbia, home to over 700,000 residents, has a larger population than Wyoming and Vermont, yet its citizens lack full voting representation in Congress. They pay federal taxes, serve in the military, and are subject to federal laws, but have only a non-voting delegate in the House and no senators. Proponents argue that this is a fundamental injustice, a form of "taxation without representation" that echoes the American Revolution. They advocate for D.C. statehood, proposing the new state be named "Douglass Commonwealth" after abolitionist Frederick Douglass, while a small federal district would remain around the core government buildings. Opponents, largely Republicans, raise concerns about the constitutionality of creating a new state from federal land, and more pragmatically, the near certainty that D.C. would elect two Democratic senators, fundamentally altering the Senate’s political balance.

Puerto Rico Statehood: A U.S. territory since 1898, Puerto Rico’s 3.2 million residents are U.S. citizens but also lack full voting representation in Congress and cannot vote in presidential elections. Its status has been a subject of ongoing debate, with options including statehood, independence, or maintaining its current commonwealth status. Plebiscites held on the island have shown varying levels of support for statehood, often influenced by economic conditions and political leadership. Proponents argue statehood would provide full democratic rights, equal access to federal programs, and a stronger economic footing. Opponents cite concerns about cultural identity, the impact on Spanish as an official language, and the potential economic burden on the federal government. Like D.C., Puerto Rico’s potential entry is also viewed through a partisan lens, with expectations it would lean Democratic.

The Fabric of the Union: Impact and Significance

The admission of new states has profoundly shaped the American identity. Each new state has brought its own unique geography, resources, industries, and cultures, enriching the national tapestry. From the vast agricultural lands of the Midwest to the mineral wealth of the Rockies, the strategic Pacific outposts of Alaska and Hawaii, and the diverse populations that settled them, each addition has contributed to the nation’s economic engine and cultural mosaic.

The process has also served as a testament to the nation’s enduring commitment to self-governance and democratic expansion. While often messy and politically charged, the mechanism of admitting new states has allowed the Union to grow organically, incorporating new peoples and territories under the umbrella of shared constitutional principles. It reflects the "E Pluribus Unum" – out of many, one – ethos, constantly striving to bring diverse elements into a unified whole.

Looking Ahead: An Enduring Legacy

The saga of admitting new states is far from over. As debates continue over Washington D.C. and Puerto Rico, and as the U.S. continues to evolve, the question of whether and how to expand the Union will remain a recurring feature of American political life. Each admission is more than just a legislative act; it is a profound declaration about who "We the People" are, and who we aspire to be. It is a dynamic process that has shaped America’s past, defines its present, and will undoubtedly influence its future, reinforcing the idea that the "more perfect Union" is an ongoing, evolving experiment.