In the vast, silent expanse of western Kansas, where the prairie wind whispers tales of a bygone era, lie the barely discernible echoes of Fort Downer. Not a grand fortress of stone and cannon, but rather a crude, temporary outpost, Fort Downer existed for little more than a flicker in the sweeping drama of America’s westward expansion. Yet, its fleeting presence, its harsh realities, and its rapid demise offer a potent microcosm of the relentless push of Manifest Destiny, the clash of cultures, and the unyielding will of those who sought to tame a wild frontier.

To understand Fort Downer, one must first grasp the tumultuous landscape of post-Civil War America. The nation, scarred but unified, looked westward with renewed vigor. The promise of land, opportunity, and untold riches fueled a relentless migration. At the vanguard of this movement was the railroad, the iron horse thundering across the plains, symbolizing progress and connecting the burgeoning East with the untapped resources of the West. In Kansas, the Kansas Pacific Railway was carving its path, an artery of empire stretching towards Denver, a lifeline for settlers and a conduit for commerce.

However, this march of progress was not unopposed. For millennia, the Great Plains had been the ancestral hunting grounds and spiritual home of powerful Native American nations – the Cheyenne, Arapaho, Sioux, and others. The encroachment of settlers, the decimation of buffalo herds, and the relentless construction of the railroad were direct threats to their way of life, their sovereignty, and their very survival. Raids on railroad construction crews, stagecoaches, and isolated homesteads became increasingly frequent and brutal, a desperate defense against an unstoppable tide.

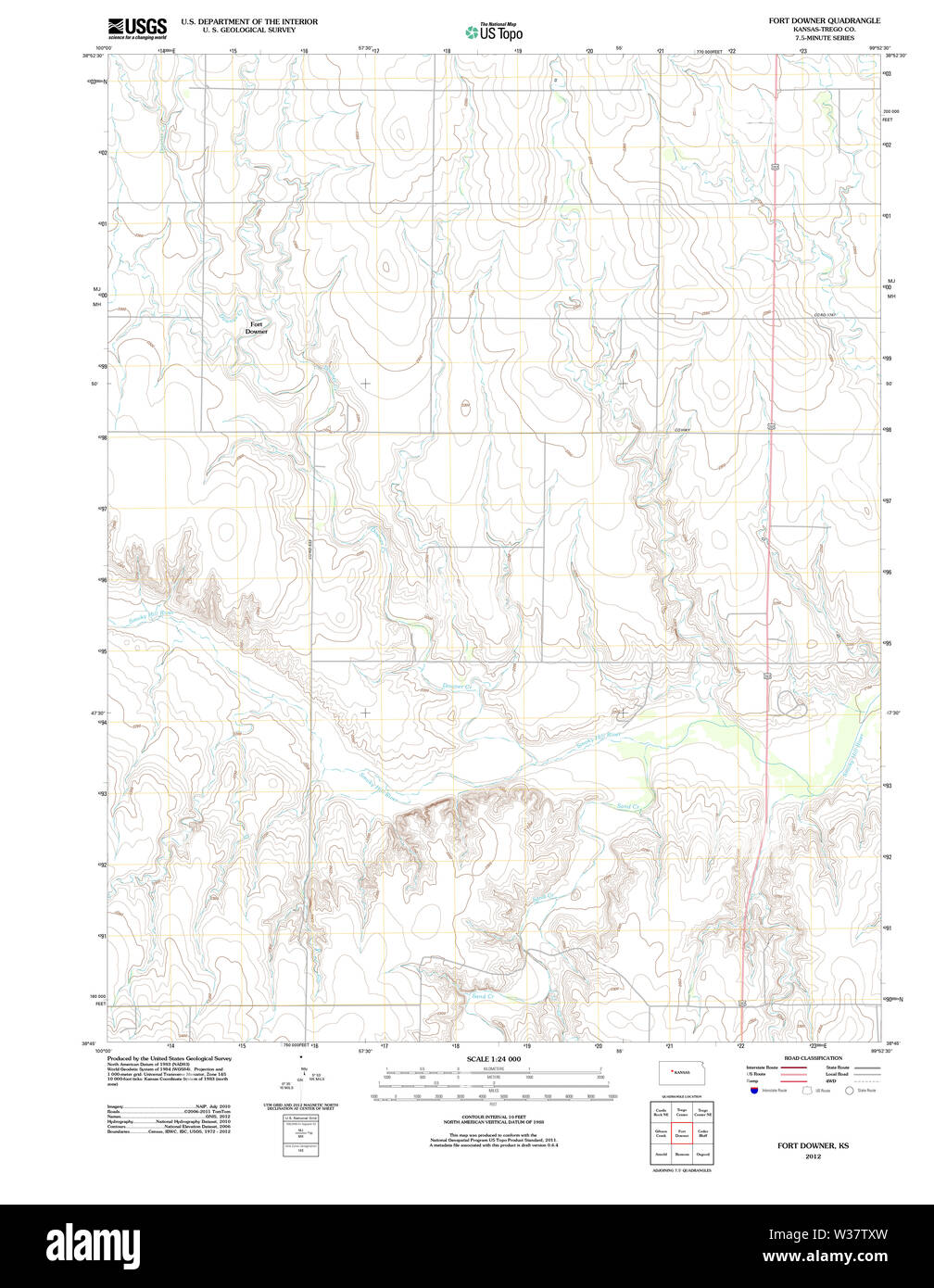

It was amidst this volatile backdrop that the U.S. Army, tasked with protecting the burgeoning infrastructure and the lives of those who ventured westward, established a series of small, strategic outposts. Fort Downer, established in late 1867, was one such installation. Located in what is now Logan County, Kansas, near the forks of the Smoky Hill River and along the nascent Kansas Pacific route, its primary mission was clear: to provide security for the railroad workers, the stage lines of the Butterfield Overland Despatch, and the trickle of settlers braving the untamed wilderness.

Life at Fort Downer was a stark testament to the unforgiving nature of the frontier. Unlike the more established, permanent forts like Fort Hays or Fort Wallace, Downer was essentially a temporary encampment. Its structures were crude, hastily constructed from sod, logs, and whatever scant materials could be scavenged. These were not the imposing stone walls of European castles, but rather humble, often leaky, shelters against the elements. A soldier’s life here was a constant battle against isolation, extreme weather, disease, and the ever-present threat of attack.

Garrisoned by detachments of cavalry and infantry, often young, inexperienced men from diverse backgrounds, the soldiers endured conditions that would break lesser spirits. The Kansas plains could be brutally hot in summer, with temperatures soaring and water sources scarce. Winters brought blizzards that could trap men for days, with temperatures plummeting far below zero. Disease, particularly dysentery and cholera, was a constant companion, often claiming more lives than enemy arrows or bullets. Supplies were often late or insufficient, leading to meager rations and tattered uniforms.

Their days were a monotonous cycle of drills, guard duty, and patrols. Soldiers rode out, often for days at a time, scouting the vast plains for signs of hostile activity, guarding construction crews, or escorting stagecoaches. These patrols were not only physically exhausting but mentally taxing, as every rise in the land, every rustle in the tall grass, could signal an ambush. The silence of the plains could be deafening, broken only by the howl of the wind or the distant cry of a coyote, amplifying the sense of isolation and vulnerability.

Yet, moments of intense, visceral violence could erupt without warning. Native American warriors, masters of the terrain and guerrilla tactics, would strike swiftly and disappear back into the vastness. Their attacks were often aimed at disrupting the railroad, killing or capturing workers, stealing horses, or driving off livestock – a direct challenge to the white man’s encroachment. For the soldiers at Fort Downer, the line between boredom and terror was often razor-thin. They were frontline participants in a brutal, no-quarter conflict, a clash between two irreconcilable ways of life.

The strategic importance of the railroad cannot be overstated in this conflict. General William Tecumseh Sherman, a key architect of the Union victory in the Civil War and later commander of the Military Division of the Missouri, understood this implicitly. He famously (and controversially) advocated for a harsh strategy against the Plains tribes, believing that the only way to secure the West was to break their will and destroy their means of subsistence. While the infamous quote "The only good Indian is a dead Indian" is often attributed to him, it reflects a prevailing, brutal sentiment of the era, where the extermination or forced removal of Native Americans was seen by many as a necessary evil for the sake of "progress." Forts like Downer were instruments of this policy, pushing the frontier ever westward, regardless of the human cost.

Despite the hardships and the ever-present danger, the soldiers at Fort Downer played a critical role. Their presence, however small, provided a modicum of security that allowed the Kansas Pacific to continue its construction. Each mile of track laid was a victory, each successful stagecoach journey a small triumph in the face of overwhelming odds. They were the thin blue line, stretched to its breaking point, defending the dream of a transcontinental nation.

However, the very factors that necessitated Fort Downer’s creation also led to its rapid obsolescence. The frontier was constantly shifting. As the railroad pushed further west and more permanent, larger forts like Fort Wallace and Fort Hays solidified their presence, the need for smaller, temporary outposts diminished. By 1868, just a year after its establishment, the primary mission of Fort Downer had largely been fulfilled or rendered redundant by the changing military landscape. The intense skirmishes that defined its early existence began to subside in its immediate vicinity, shifting further west.

Thus, Fort Downer’s existence was remarkably brief. It was abandoned sometime in late 1868 or early 1869, its purpose served. The soldiers packed their meager belongings, struck their flags, and marched away, leaving the crude structures to the mercy of the elements. The prairie, a relentless and efficient force, quickly began to reclaim its own. The sod walls crumbled, the logs rotted, and the wind and rain systematically erased almost all traces of human habitation. Within a few years, little remained but a few depressions in the ground, a scattered bullet casing, or a forgotten button – silent witnesses to a fleeting moment in history.

Today, Fort Downer is not a tourist destination with grand ruins or meticulously restored buildings. It exists primarily as a historical marker, a point on a map, and a subject of archaeological interest. Its physical remains are scant, requiring a keen eye and a deep appreciation for history to even identify its approximate location. Yet, its story, though brief, resonates profoundly.

Fort Downer stands as a powerful symbol of the American frontier: its raw beauty, its brutal realities, and the incredible speed with which history unfolded. It represents the courage and endurance of the soldiers who served there, the tenacity of the railroad builders, and the tragic struggle of the Native American tribes fighting for their homeland. It reminds us that "progress" often came at an immense cost, both human and cultural.

In its silence, Fort Downer speaks volumes. It tells of a nation driven by expansion, of men and women facing unimaginable hardships, and of a pivotal era when the fate of an entire continent was being forged. It is a humble, almost forgotten, outpost, but its ghost lingers on the Kansas plains, a poignant reminder that even the shortest chapters can hold the most profound lessons about the making of America.