Fort Gadsden: Echoes of Freedom and Fire on the Apalachicola

On a sweltering August afternoon in 1816, along the winding Apalachicola River in what is now Florida, a single, impossibly lucky shot changed the course of American history, extinguishing a beacon of freedom and igniting a forgotten chapter of racial conflict. A cannonball, fired from a U.S. Navy gunboat, arced through the humid air, struck the powder magazine of a formidable fort, and detonated with an earth-shattering roar. The explosion obliterated the stronghold, killing an estimated 270-300 people – a catastrophic loss of life that, for its time, was unparalleled in Florida. This wasn’t just any fort; it was a sanctuary, a thriving community of escaped slaves and their Native American allies, built on the promise of liberty, and feared as a dangerous symbol of defiance by the slaveholding South. Its destruction marked a brutal end to an audacious experiment in self-governance and paved the way for the United States to assert its dominion over a contested frontier.

Today, the site is known as Fort Gadsden Historical Site, a serene, moss-draped landscape managed by the U.S. Forest Service. But the tranquility belies a tumultuous past, a story of imperial ambition, racial tension, and the relentless human quest for freedom. To understand Fort Gadsden, one must first understand its origins as "Negro Fort" or "Nicholls’ Outpost," a powerful testament to the complex and often brutal realities of early 19th-century America.

A British Legacy: The Birth of a Haven

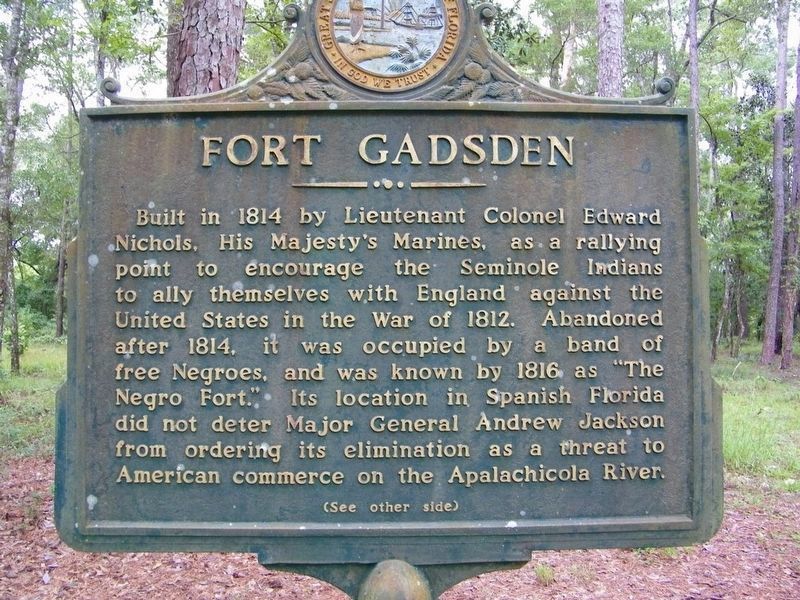

The story of the Negro Fort begins in the tumultuous backdrop of the War of 1812. While the main theater of conflict raged in the North, the British, seeking to disrupt American expansion and exploit existing tensions, turned their attention to the vulnerable Southern frontier. Florida, still under Spanish control but weakly governed, offered a strategic base. In 1814, a British expeditionary force led by Colonel Edward Nicholls established a post at Prospect Bluff, a commanding position overlooking the Apalachicola River, approximately 60 miles inland from the Gulf of Mexico.

Nicholls’ objective was twofold: to recruit Native American allies, primarily Seminole and Creek warriors, and to enlist escaped slaves, known as "Maroons," into the British service. He offered them freedom, arms, and training, promising them land and protection in exchange for fighting against the Americans. This was a shrewd, if cynical, move. For the Maroons, many of whom had fled plantations in Georgia and Alabama, it was an irresistible offer – a chance to secure the liberty they had so desperately sought. For the Native Americans, it was an opportunity to resist the encroaching American settlers who threatened their ancestral lands.

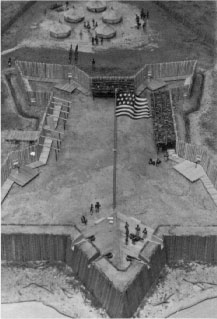

Under Nicholls’ guidance, a substantial fort was constructed. It was a formidable structure, strategically located, with a perimeter of thick earthworks, a ditch, and a palisade. Inside, it housed an arsenal of British cannons, muskets, and a large powder magazine. When Nicholls and his main force departed after the Treaty of Ghent officially ended the War of 1812 in early 1815, they left the fort in the hands of their Black and Native American allies, along with a considerable quantity of arms and ammunition. A British Royal Marine officer, Captain George Woodbine, was left in command, providing continued support and training. He reportedly told the occupants that they were now "a free and independent people" and that the British would always protect them.

The Republic of Prospect Bluff: A Society of the Free

For the next year and a half, the Negro Fort, as it became known to the Americans, flourished as a self-governing community. Estimates vary, but its population likely ranged from 800 to 1,000 people, comprising primarily Maroons, but also Seminole and Creek families who found common cause with the escaped slaves. This was no mere military outpost; it was a burgeoning society. The inhabitants cultivated extensive fields of corn, beans, and other crops, fished the rich waters of the Apalachicola, and hunted the abundant wildlife. They built homes, raised families, and developed a vibrant culture of resistance and self-reliance.

The fort served as a beacon of hope for thousands of enslaved people across the South. News of its existence spread like wildfire through the slave quarters, inspiring more to risk everything for a chance at freedom. It was, in essence, a de facto republic, a living refutation of the fundamental tenets of American slavery, existing just across the border from U.S. territory.

Historian J. Leitch Wright Jr. described it as "a black nation within a nation, a fortress of defiance against white authority." For its inhabitants, it was a hard-won sanctuary, a place where their humanity was recognized, and their freedom defended with arms.

American Apprehension: A Threat to the Peculiar Institution

To the slaveholding states of Georgia and Alabama, the Negro Fort was an intolerable affront, a dangerous precedent that threatened the very foundation of their economic and social order. Its existence was a direct challenge to the institution of slavery and a constant source of anxiety. Plantation owners lived in fear of slave revolts, and the idea of an armed, self-sufficient community of freed slaves providing refuge and inspiration to others was a nightmare scenario.

General Andrew Jackson, the formidable military commander of the Southern District, famously declared it a "nest of outlaws and runaways" and a "source of annoyance" that needed to be eliminated. He viewed the fort not merely as a military threat, but as an existential one to the racial hierarchy he championed. Even after the war, Jackson maintained that the fort was a British provocation, a violation of American sovereignty, despite its location on Spanish soil.

The U.S. government initially attempted diplomatic solutions, demanding that Spain dismantle the fort. However, Spain, weakened and preoccupied with its own colonial struggles, lacked the power or the will to confront the armed community. With diplomacy failing, and under immense pressure from Southern slaveholders, the United States decided to take matters into its own hands.

The Siege and Devastation: August 1816

In the summer of 1816, General Edmund Gaines, acting under Jackson’s authority, ordered a combined land and naval assault on the Negro Fort. A detachment of U.S. Army soldiers and allied Creek warriors marched overland, while two U.S. Navy gunboats, under the command of Lieutenant Commander J.D. Henley, sailed up the Apalachicola River. The naval vessels, armed with powerful cannons, were crucial to the American strategy.

The defenders of the fort, led by a Black commander named Garçon and a Choctaw chief, were prepared for a fight. They had ample ammunition and several heavy cannons. For several days, a standoff ensued, with sporadic exchanges of fire. The American ground forces positioned themselves to cut off escape routes, while the gunboats moved into position on the river.

On August 21, 1816, the decisive moment arrived. The U.S. Navy gunboats began a sustained bombardment of the fort. While many of their shots were ineffective, one proved tragically precise. A heated cannonball, likely a "hot shot" designed to ignite wooden structures, pierced the wall of the fort and landed directly in the open powder magazine. The resulting explosion was cataclysmic.

"The effect was awful," reported Lieutenant Henley. "The Fort was blown up, and with it the most of the Negroes and Indians." The blast was heard for miles, sending debris and bodies high into the air. Of the nearly 300 people inside the fort, only about 60 survived, many severely wounded. The few survivors, including Garçon, were captured. Garçon and the Choctaw chief were summarily executed by the Creek allies of the Americans, reportedly on Jackson’s orders, in a brutal act of retribution. Most of the other survivors were re-enslaved.

The destruction of the Negro Fort was a devastating blow to the cause of freedom for escaped slaves in Florida. It sent a clear message that the United States would tolerate no armed challenge to its slave system, even on foreign soil. It also solidified American control over the Apalachicola River, a vital waterway for trade and military operations, and paved the way for future conflicts with the Seminoles and further U.S. incursions into Spanish Florida.

Fort Gadsden: A New Purpose, A Different Name

The site of the obliterated Negro Fort did not remain abandoned for long. Recognizing its strategic importance, the United States Army soon established a new post on the bluff. This time, it was an American fort, built with American intentions. It was named Fort Gadsden, in honor of Lieutenant James Gadsden, the U.S. Army engineer who oversaw its construction.

Fort Gadsden served as a crucial supply depot and staging area for U.S. forces during the First Seminole War (1817-1818), a conflict largely precipitated by the very issues that led to the Negro Fort’s destruction – American expansionism, the pursuit of runaway slaves, and the desire to control Florida. Andrew Jackson himself used Fort Gadsden as his headquarters during his infamous invasion of Florida in 1818, which ultimately led to the Adams-Onís Treaty of 1819, ceding Florida to the United States.

However, once Florida became U.S. territory, the need for a fort at Prospect Bluff diminished. The frontier moved further south, and the logistical challenges of maintaining the remote outpost eventually led to its abandonment by the U.S. Army in 1821. The structures slowly deteriorated, reclaimed by the relentless Florida wilderness.

Legacy and Remembrance

For generations, the story of the Negro Fort, and the initial destruction that preceded the American Fort Gadsden, remained largely forgotten or deliberately suppressed in mainstream American history. It was a narrative that complicated the heroic image of westward expansion and exposed the brutal realities of slavery and racial warfare.

In the mid-20th century, however, a renewed interest in African American history and civil rights brought the story back into focus. In 1961, the site was designated a National Historic Landmark, recognizing its profound significance. Today, the Fort Gadsden Historical Site is a tranquil park, maintained by the U.S. Forest Service. Visitors can walk among the earthworks, which are still discernible, and read interpretive signs that recount the dramatic events that unfolded there. A monument stands in solemn remembrance of the lives lost in the explosion, commemorating the courage and sacrifice of those who fought for their freedom.

The story of Fort Gadsden, and its predecessor the Negro Fort, is more than just a historical footnote. It is a powerful reminder of the complex tapestry of American identity, woven with threads of liberation and oppression, resistance and conquest. It highlights the strategic importance of Florida in the early republic, the ruthless pursuit of economic interests tied to slavery, and the enduring human spirit that dared to dream of and fight for freedom, even against overwhelming odds. The echoes of that fiery August afternoon in 1816 still resonate, a testament to a forgotten republic born of courage and extinguished by cannon fire, yet whose spirit continues to inspire.