Fort Goodwin: Arizona’s Forgotten Crucible of Conflict and Disease

By [Your Name/Journalist Name]

The Arizona sun beats down mercilessly, just as it did over a century and a half ago, baking the vast, unforgiving landscape. Today, the Gila River Valley near modern-day San Carlos whispers secrets only the wind remembers. There, amidst the mesquite and creosote, lie the spectral echoes of Fort Goodwin – a military outpost that, despite its brief existence, played a pivotal, if often overlooked, role in the brutal crucible of the Apache Wars. It was a place of strategic ambition, relentless hardship, and a grim testament to the human cost of America’s westward expansion.

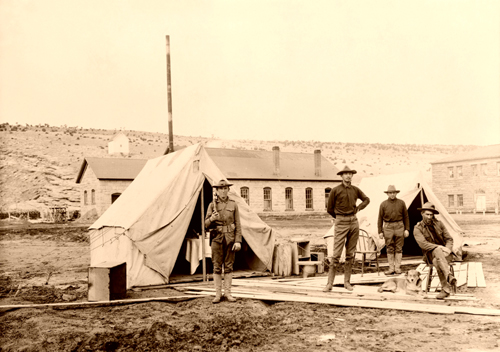

Fort Goodwin was not a fort of grand stone walls or towering bastions. It was a collection of adobe and log structures, hastily erected and perpetually struggling against the elements and the diseases that plagued its inhabitants. Established in 1864, in the midst of the American Civil War, its purpose was not to fight Confederates but to assert Union authority over the newly formed Arizona Territory and, more critically, to "pacify" the indigenous Apache people whose ancestral lands were increasingly encroached upon by miners, ranchers, and settlers.

A Strategic, Yet Perilous, Location

The decision to place Fort Goodwin was a calculated one, driven by the iron will of Brigadier General James H. Carleton, commander of the Department of New Mexico, which then included Arizona. Carleton envisioned a network of forts that would control the major routes and strategic valleys, effectively isolating and containing the Apache bands. The chosen site, on the south bank of the Gila River, near the confluence of the San Carlos River, offered control over the vital Gila River Trail, a key artery for settlers and supplies, and placed troops squarely in the heart of Aravaipa and Chiricahua Apache territory.

Yet, this strategic advantage came at a terrible price. The Gila River Valley, while vital for water, was notoriously unhealthy. Malaria, dysentery, and scurvy were not just common ailments; they were constant companions, often more deadly than Apache arrows. The humid conditions near the river, combined with poor sanitation and a lack of fresh provisions, turned Fort Goodwin into a veritable hospital.

"More men died of fever and ague at Fort Goodwin than were ever killed by Indians," one contemporary account lamented, a sentiment echoed in countless soldiers’ letters and official reports. The summer heat was crushing, often exceeding 110 degrees Fahrenheit, making physical labor and even simple existence a grueling test of endurance. Water, though available, was often stagnant or contaminated. Supplies were erratic, traveling hundreds of miles across rugged, hostile terrain. Morale plummeted, and desertion rates soared.

Life on the Frontier’s Edge

Life for the soldiers, primarily volunteers from California and later regular U.S. Army troops, was a monotonous cycle of patrols, guard duty, and the constant battle against disease. Their uniforms, designed for temperate climates, were ill-suited for the Arizona desert. Food consisted largely of salt pork, hardtack, and beans, supplemented occasionally by game or meager local produce. Medical care was rudimentary at best, with limited supplies and often overworked, inexperienced surgeons.

The primary mission was to protect settlers, miners, and travelers, and to conduct "scouting expeditions" against the Apache. These were rarely pitched battles but rather long, arduous treks through mountains and deserts, tracking elusive bands, often ending in frustrating futility. The Apache, masters of their homeland, knew every canyon, every water source, and every hiding place. They employed guerrilla tactics, striking supply trains or isolated ranches, then vanishing into the vast landscape.

"We were chasing phantoms," one soldier reportedly wrote, expressing the frustration of many. "They moved like smoke, and we, laden with equipment, were always a step behind."

The Broader Conflict: A Time of Atrocities

Fort Goodwin’s existence was inextricably linked to the broader, often brutal, conflict known as the Apache Wars. This was an era marked by misunderstandings, broken treaties, and horrific violence from both sides. While Fort Goodwin itself was not the site of major battles, its troops were part of the military apparatus that enforced policies leading to events like the Camp Grant Massacre in April 1871, where nearly 150 Aravaipa Apache, mostly women and children, were slaughtered by a mob of Tucson citizens, Mexican Americans, and allied Tohono O’odham warriors.

Though Camp Grant was the epicenter of that particular atrocity, Fort Goodwin’s proximity and its troops’ involvement in subsequent actions against "renegade" Apache bands underscored the fort’s role in a conflict that offered little quarter. The fort was a symbol of federal power attempting to impose order on a chaotic frontier, often at the expense of indigenous populations. For the Apache, the forts represented an invading force, an existential threat to their way of life and their very survival. They fought fiercely to defend their homelands, their families, and their cultural identity against overwhelming odds.

The Decline and Abandonment

By 1871, after just seven years of operation, the strategic and human costs of maintaining Fort Goodwin became untenable. The relentless toll of disease, coupled with shifts in military strategy, led to its abandonment. The military concluded that the site was simply too unhealthy, and other forts, such as Camp Apache to the north and the later Camp Thomas (initially Camp San Carlos) established just a few miles upriver, offered better strategic positioning and slightly healthier conditions.

The troops, supplies, and remaining usable structures were moved. Fort Goodwin, the "hospital fort," was left to the mercies of the elements. Its adobe walls began to melt back into the earth, its timber structures collapsed, and the desert slowly reclaimed what man had briefly attempted to conquer.

A Forgotten Legacy

Today, little remains of Fort Goodwin. The site is largely within the boundaries of the San Carlos Apache Indian Reservation, a testament to the enduring presence of the very people the fort was built to control. While some archaeological remnants might exist beneath the soil, visible traces are scarce. The once-bustling parade ground, the officers’ quarters, the barracks – all have vanished, leaving only the quiet vastness of the Arizona desert.

Yet, the story of Fort Goodwin is far from insignificant. It serves as a stark reminder of the harsh realities of frontier life, the immense challenges faced by both soldiers and Native Americans, and the often-grim calculus of westward expansion. It epitomizes the struggle against the elements, against disease, and against each other.

Fort Goodwin was a microcosm of the larger conflict that defined the American Southwest in the late 19th century. It was a place where grand strategic ambitions clashed with the brutal realities of a remote, unforgiving land. It stands, in its invisible ruins, as a monument to the resilience of the human spirit, the tragic cost of conflict, and the complex, often painful, layers of American history. Its forgotten story is a vital chapter in understanding how the modern West was forged, etched in the dust and disease of a lost Arizona outpost. The whispers of Fort Goodwin, though faint, still carry the echoes of a pivotal era.