Fort Harmar: The Crucible of American Expansion in the Ohio Valley

At the confluence of the mighty Ohio and Muskingum Rivers, where the whispers of the past mingle with the currents of the present, lies the phantom imprint of Fort Harmar. Today, little remains of its physical structure, yet its historical significance looms large, a testament to the turbulent birth of the American frontier. Built in 1785, Fort Harmar was not merely a military outpost; it was a symbol of federal authority, a critical stepping stone for westward expansion, and a crucible where the nascent United States first truly confronted the complexities of its relationship with Native American nations.

The ink was barely dry on the Treaty of Paris (1783), which officially ended the American Revolutionary War and granted the fledgling United States vast territories stretching to the Mississippi River. However, this land, particularly the fertile Ohio Valley, was far from empty. It was the ancestral home of numerous powerful Native American tribes, including the Shawnee, Delaware, Wyandot, and Miami, who had fought alongside the British and viewed American expansion with deep suspicion. The immediate post-war years were marked by a dangerous power vacuum. Squatters, land speculators, and adventurers poured into the Ohio Country, leading to escalating skirmishes and a desperate need for order.

It was into this volatile environment that the federal government, under the Articles of Confederation, dispatched General Josiah Harmar, a seasoned veteran of the Continental Army. His mission: to establish a strong military presence to protect surveyors, deter illegal settlement, and, crucially, to assert federal control over the newly acquired Northwest Territory. In the autumn of 1785, Harmar and his troops, composed largely of inexperienced recruits, began construction of the fort at the strategic point where the Muskingum flowed into the Ohio.

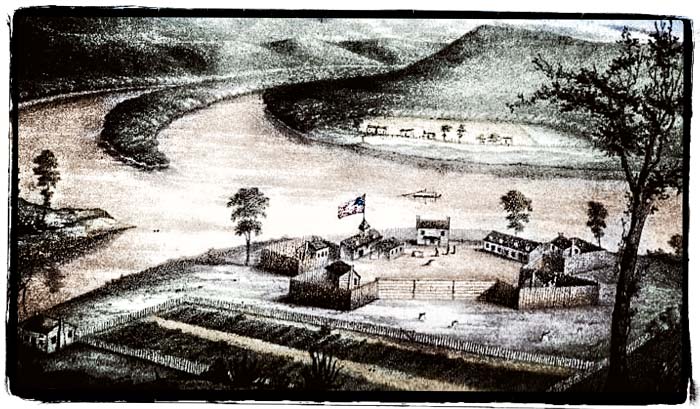

"This is a country of immense resources, and if properly settled, will add greatly to the strength and prosperity of the United States," George Washington, keenly aware of the strategic importance of the Ohio Valley, had written. The establishment of Fort Harmar was a direct response to this vision, a physical manifestation of the government’s commitment to securing the territory. The fort itself was a formidable, if rudimentary, structure. Built primarily of timber, it was an 180-foot square stockade, fortified with four blockhouses at its corners, each mounting a cannon. Barracks, a storehouse, and officers’ quarters filled the interior, all designed to withstand attack and provide a measure of comfort in the harsh wilderness.

Life within the palisades was a stark testament to frontier endurance. Soldiers, often poorly paid and supplied, faced isolation, disease, and the constant threat of attack. Malaria, dysentery, and other ailments were rampant, claiming more lives than enemy engagements. Discipline was strict, but morale often wavered. Yet, for many, Fort Harmar offered a chance at a new life, a role in the grand American experiment of westward expansion. From its walls, soldiers would patrol the surrounding wilderness, protect surveying parties, and occasionally engage in skirmishes with Native American warriors defending their lands.

Fort Harmar’s most enduring legacy, however, is not its military engagements but its role as a diplomatic hub. It was here, in January 1789, that the Treaty of Fort Harmar was signed. This treaty was intended to solidify earlier agreements, particularly the Treaty of Fort McIntosh (1785), which many tribes had not recognized, arguing it was signed by individuals who did not represent the collective will of their people.

The negotiations at Fort Harmar were overseen by Arthur St. Clair, the governor of the Northwest Territory, a man burdened by the immense task of bringing order to the chaotic frontier. Representatives from various tribes, including the Wyandot, Delaware, Ottawa, Chippewa, Potawatomi, and some Seneca, gathered, though notably absent were the powerful Shawnee and Miami, who remained fiercely opposed to American encroachment.

The treaty itself was less a negotiation and more an assertion of American will. St. Clair, operating under instructions from the Confederation Congress, largely reaffirmed the land cessions made in the Treaty of Fort McIntosh, which granted vast tracts of land north of the Ohio River to the United States. The Native American representatives, facing overwhelming military pressure and a dwindling resource base, had little leverage. They were offered annuities – annual payments of goods – in exchange for their claims.

Historian Francis Paul Prucha notes in "The Great Father: The United States Government and the American Indians" that the Fort Harmar treaty, like many others of its era, was fundamentally flawed by a lack of genuine consent from all affected parties. "The government’s policy was one of extinguishing Indian titles by treaty, but the methods used often left much to be desired in terms of fairness and equity," Prucha observed. Many Native American leaders viewed the treaty as a forced concession, signed under duress, and lacking the unanimous consent required by their traditional governing structures.

As a Wyandot chief reportedly declared at the time, expressing the deep distrust felt by many, "We cannot give up our hunting grounds without the consent of all our brothers, and many are not here." This sentiment proved prophetic. The ink on the treaty parchment was barely dry when the skirmishes escalated into open warfare. The Shawnee and Miami, in particular, refused to acknowledge the treaty’s legitimacy, viewing it as an illegal seizure of their ancestral lands. They formed a formidable confederacy, determined to resist further American expansion by force.

The failure of the Treaty of Fort Harmar to bring lasting peace plunged the Ohio Valley into a decade of intense conflict, often referred to as the Northwest Indian War. General Harmar himself led a disastrous expedition against the Miami and Shawnee in 1790, suffering a significant defeat that underscored the strength of Native American resistance. This defeat, alongside subsequent American failures, highlighted the urgent need for a more effective military strategy and a clearer Indian policy.

Ultimately, it would take the decisive victory of General Anthony Wayne’s Legion at the Battle of Fallen Timbers in 1794, followed by the Treaty of Greenville in 1795, to finally establish American dominance in the Ohio Valley. By then, Fort Harmar’s direct military importance had waned. With the frontier moving westward and the immediate threat in the Ohio Valley diminished, the fort was decommissioned. Its timber and materials were gradually dismantled and repurposed, many of them finding new life in the construction of the burgeoning town of Marietta, the first permanent American settlement in the Northwest Territory, founded in 1788 just across the Muskingum River from the fort.

Today, Fort Harmar exists primarily in historical records and on interpretive markers. A small park at the confluence of the rivers in Marietta commemorates its location, offering visitors a glimpse into the strategic landscape that once defined this crucial outpost. The remnants of its earthworks may still lie buried beneath the modern cityscape, silent witnesses to a pivotal era.

Fort Harmar stands as a profound, if largely unseen, monument to the complex tapestry of early American history. It represents the federal government’s nascent attempts to assert its authority, the relentless drive of westward expansion, and the tragic, often violent, encounter between European-American settlers and the indigenous peoples of the continent. It was a place where visions of empire met the harsh realities of the wilderness, where treaties were signed and broken, and where the foundational struggles of a young nation played out on a rugged frontier. While its physical presence has faded, the echoes of Fort Harmar resonate, reminding us of the sacrifices, conflicts, and pivotal decisions that forged the American landscape we know today.