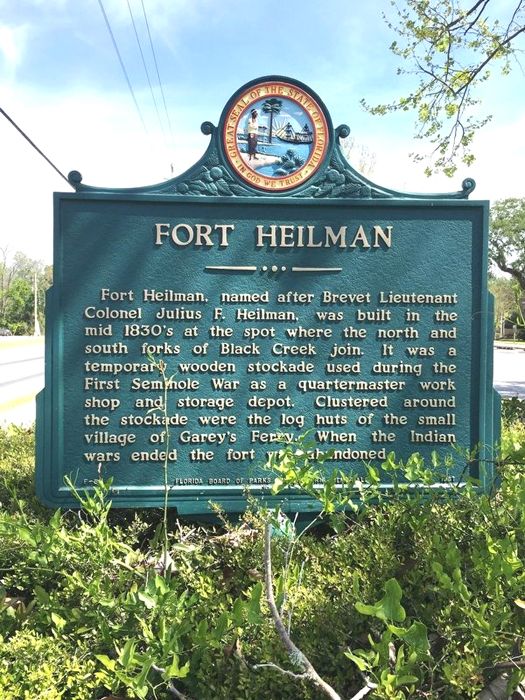

Fort Heilman: Unearthing the Ghost of Florida’s Bloodiest War

Beneath the tranquil canopy of oaks and pines in Clay County, Florida, where children’s laughter now echoes through Camp Chowenwaw Park, lies a silent sentinel of a brutal past: Fort Heilman. It is not a grand, imposing structure, nor a meticulously preserved landmark. Instead, its remains are largely invisible to the untrained eye, a testament to the relentless power of nature and the passage of time. Yet, for archaeologists and historians, Fort Heilman is a precious window into one of America’s most protracted and tragic conflicts – the Second Seminole War.

This unassuming site on the banks of Black Creek, just upstream from its confluence with the St. Johns River, was once a vital, if perilous, outpost. From 1837 to 1842, it served as a critical supply depot, hospital, and staging ground for U.S. troops battling the tenacious Seminole people. Today, its rediscovery and ongoing excavation are shedding new light on the daily lives of soldiers, the strategic imperatives of the war, and the enduring legacy of a conflict often overshadowed by more celebrated chapters of American history.

A Nation’s Expansion, a People’s Resistance

To understand Fort Heilman’s significance, one must first grasp the broader context of the Second Seminole War (1835-1842). This was not merely a localized skirmish but a desperate struggle fueled by America’s insatiable hunger for land and the federal government’s policy of Indian Removal. Following the Indian Removal Act of 1830, the U.S. government sought to relocate all Native American tribes east of the Mississippi River to designated territories in the West. While many tribes, under immense pressure, reluctantly signed treaties, the Seminoles of Florida, a diverse group including Muscogee-speaking people and descendants of escaped enslaved Africans, fiercely resisted. They had carved out a life in Florida’s vast, unforgiving wilderness – a landscape of dense hammocks, impenetrable swamps, and meandering rivers that they knew intimately.

Florida, still a relatively new U.S. territory acquired from Spain in 1819, was seen as ripe for development. Its fertile lands were coveted by cotton planters, and its strategic location offered access to lucrative trade routes. But the Seminoles, led by charismatic figures like Osceola, Micanopy, and Billy Bowlegs, stood in the way. Their refusal to abandon their ancestral lands ignited a war that would become the longest and costliest Indian conflict in U.S. history, both in terms of human lives and financial expenditure.

The Strategic Imperative of Fort Heilman

Fort Heilman’s location was no accident. The St. Johns River was Florida’s primary artery, allowing the transport of troops, supplies, and provisions deep into the interior. Black Creek, a major tributary, offered further penetration into the wilderness, reaching closer to the Seminoles’ strongholds. Established in 1837, Fort Heilman became a linchpin in the U.S. Army’s strategy, under commanders like General Thomas Jesup. It was named for Dr. Joseph Heilman, a U.S. Army surgeon who died in Florida in 1836, likely from disease, a common and often deadlier foe than the Seminole warriors.

"The St. Johns River was the Interstate 95 of its day for military logistics," explains Dr. Keith Ashley, an archaeologist at the University of North Florida, who has spearheaded the archaeological investigations at Fort Heilman. "Fort Heilman’s position on Black Creek meant it was perfectly situated to receive supplies from steamboats coming up the St. Johns and then redistribute them by wagon or smaller boats to other interior forts." Without a robust network of supply depots like Heilman, the U.S. Army’s campaigns in the dense, hostile Florida environment would have been impossible.

The fort itself was likely a relatively simple construction: a palisade of sharpened logs surrounding a few wooden structures – barracks, a hospital, a blockhouse for defense, and storage facilities. It was designed for utility and defense, not comfort or permanence.

Life in the Crucible: Disease, Despair, and Determination

Life at Fort Heilman was a harsh existence. The Florida climate, with its oppressive heat, suffocating humidity, and relentless insect populations, was a constant torment. Malaria, yellow fever, dysentery, and other diseases ran rampant, often claiming more lives than enemy fire. Soldiers, many unaccustomed to such conditions, faced a dual threat: the unseen microbial killers and the ever-present danger of a Seminole ambush from the surrounding wilderness.

Garrison sizes varied, but a typical fort might house a few companies of infantry or artillery, along with civilian contractors, teamsters, and surgeons. Their days would have been a monotonous cycle of drills, guard duty, and the arduous task of unloading and reloading supplies. The sounds would have been a mix of military commands, the creak of wagons, the distant calls of wild animals, and the ever-present buzzing of mosquitoes. The smell would have been a blend of gunpowder, sweat, pine resin, and the grim realities of a field hospital.

"These soldiers were fighting in an environment completely alien to most of them," says historian John T. Sprague, whose 1848 account of the war remains a crucial primary source. "The swamps were their greatest enemies, and the Seminoles, masters of that terrain, used it to their utmost advantage." For the soldiers at Fort Heilman, every patrol outside the palisade was a foray into potentially hostile territory, every journey on Black Creek a gamble with unseen dangers.

A Strategic Hub in a Brutal War

While Fort Heilman didn’t witness major pitched battles, its role was foundational. It supported the numerous expeditions launched from the St. Johns River region. It was here that sick and wounded soldiers were brought for treatment, often after grueling journeys through the wilderness. It was here that fresh troops were mustered before being sent into the heart of Seminole territory. The fort became a symbol of the U.S. Army’s relentless, if often frustrated, effort to subdue the Seminoles.

The war itself was characterized by small-scale skirmishes, ambushes, and a protracted cat-and-mouse game through the swamps. The Seminoles, though vastly outnumbered and outgunned, employed highly effective guerrilla tactics, striking quickly and vanishing into the familiar landscape. The U.S. Army, hampered by a lack of knowledge of the terrain and an underestimation of Seminole resolve, struggled to gain a decisive advantage. The war dragged on for seven years, costing the lives of an estimated 1,500 U.S. soldiers (mostly from disease) and countless Seminoles, not to mention a staggering $40 million – an astronomical sum in the 1830s.

One of the war’s most controversial episodes, the capture of Osceola under a flag of truce in 1837, occurred not far from Fort Heilman. While not directly at the fort, this event, which took place near St. Augustine, underscored the desperation and moral compromises made by U.S. commanders in their efforts to end the conflict.

The Fort’s Demise and Rediscovery

As the war slowly wound down, with many Seminoles either killed, captured, or forced to relocate, the need for forward operating bases like Fort Heilman diminished. By 1842, the fort was abandoned, its structures left to the mercy of the elements. The dense Florida wilderness quickly reclaimed the site, swallowing the palisades, barracks, and blockhouses. For over a century, Fort Heilman was little more than a whisper in history books, its exact location lost to the encroaching forest.

Its rediscovery began in earnest in the early 2000s, spearheaded by Dr. Keith Ashley and his team from the University of North Florida. Utilizing historical maps, land records, and modern archaeological techniques, they began to systematically search the grounds of Camp Chowenwaw Park, a property owned by Clay County. The breakthrough came with the identification of tell-tale artifacts and subtle changes in topography.

"When we first started, it was incredibly challenging," Dr. Ashley recounts. "The site had been plowed over, disturbed by farming, and then covered by mature trees. But we started finding fragments of military buttons, musket balls, lead shot, ceramic shards, and even structural evidence like post holes and brick fragments. It was like putting together a giant, complex puzzle."

The archaeological digs have since confirmed the fort’s precise location and yielded a treasure trove of artifacts that paint a vivid picture of life at the outpost. Recovered items include U.S. Army uniform buttons (infantry, artillery, medical), percussion caps, gunflints, lead musket balls, fragments of ceramic plates and bottles, and even animal bones, providing insight into the soldiers’ diet. Each artifact, no matter how small, tells a story of a soldier’s daily life, a meal eaten, a weapon fired, a uniform worn in the crucible of war.

A Lingering Legacy

Today, Fort Heilman remains an active archaeological site, protected within the boundaries of Camp Chowenwaw Park. While there are no grand reconstructions, interpretive signs guide visitors to the general area, allowing for reflection on the site’s profound history. The ongoing work at Fort Heilman serves several crucial purposes. It helps to meticulously document a pivotal, yet often overlooked, chapter in American military history. It provides tangible evidence of the lives and struggles of the soldiers who served there. And critically, it offers a tangible link to the Seminole people’s unwavering resistance and their enduring connection to the land.

The Second Seminole War, with its immense human cost and the eventual forced removal of most of the tribe, left an indelible scar on Florida’s history. The war highlighted the profound cultural clash between a burgeoning industrial nation and an indigenous people determined to maintain their way of life. Fort Heilman, a seemingly insignificant outpost lost to time, now stands as a poignant reminder of that conflict. It is a place where history isn’t just read in books but is slowly, painstakingly unearthed from the very soil, whispering stories of courage, suffering, and the relentless march of a nation’s expansion. Its continued study ensures that the sacrifices made on both sides of that brutal war are not forgotten, but instead serve as a vital lesson for future generations.