On the vast, windswept plains of western Kansas, where the sky seems to stretch into infinity and the only sound is the rustle of prairie grass, lie the crumbling remnants of a forgotten sentinel. Fort Henning, an outpost of the U.S. Army, once stood as a vital, if isolated, bulwark against the raw forces of the American frontier. Though its physical presence has largely succumbed to time and the elements, the echoes of its past resonate through the landscape, telling a story of courage, hardship, and the relentless march of westward expansion.

Established in 1865, in the turbulent aftermath of the Civil War, Fort Henning was born out of necessity. The Kansas frontier was a volatile mosaic of opportunity and peril. Settlers, prospectors, and pioneers were pouring into the region, drawn by the promise of land and resources, but their westward journey was often fraught with danger. Indigenous tribes, primarily the Cheyenne and Arapaho, fiercely resisted the encroachment on their ancestral lands, leading to frequent skirmishes and raids. The vital Santa Fe Trail, a major artery for trade and migration, snaked through the territory, requiring protection. The nascent railroad lines, pushing ever westward, also needed safeguarding from both environmental challenges and hostile encounters.

Named in honor of Major Thomas Henning, a respected cavalry officer tragically killed during an engagement with a band of Cheyenne warriors near the Smoky Hill River a year prior to the fort’s construction, Fort Henning was strategically positioned. It was located near a natural spring and a fordable section of the Smoky Hill River, providing crucial access to water and a defensible position along a well-used route. Its mission was clear: protect the stagecoach lines, patrol the trails, guard survey parties, and serve as a supply depot for troops operating deeper in the territory.

Life at Fort Henning was a relentless crucible for the approximately 75-100 soldiers, often a mix of battle-hardened Civil War veterans and fresh recruits. The Kansas weather, notorious for its extremes, was a constant adversary. Blistering summers brought drought and dust storms, while savage winters delivered blizzards that could isolate the fort for weeks. Disease, particularly cholera and dysentery, was a more insidious threat than any arrow or bullet, claiming lives with grim regularity due to poor sanitation and limited medical knowledge.

"Our greatest enemy here is not always the arrow or the rifle, but the gnawing loneliness and the unforgiving sun," wrote Colonel Alistair Finch, one of the fort’s longest-serving commanders, in his dispatches of 1871. His words capture the profound sense of isolation that permeated life on the remote prairie. Daily routines were rigid and monotonous, punctuated by drills, patrols, and the constant maintenance of the fort’s adobe and timber structures. Yet, this isolation also forged an unbreakable camaraderie among the men, a bond essential for survival in such a challenging environment.

The fort itself was a modest affair, typical of many frontier outposts. A rough palisade of cottonwood logs initially encircled a collection of low-slung adobe and timber buildings: barracks, an officer’s quarters, a mess hall, a commissary, a stable, and a small hospital. A parade ground occupied the center, often dusty in summer and muddy in spring. Over time, more permanent stone foundations were laid, and a blockhouse was added for enhanced defense. The sounds of reveille and retreat, the clatter of sabers, and the bark of orders were the daily soundtrack to this rugged existence.

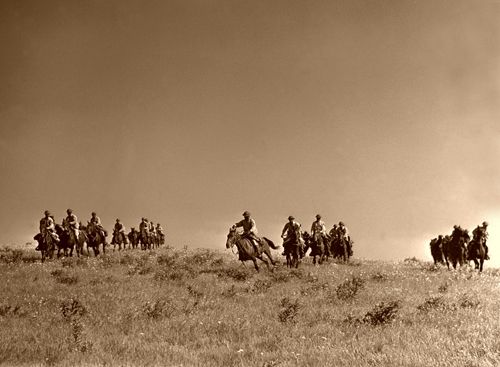

Fort Henning played its part in several significant, albeit localized, conflicts. One of the most notable was the "Battle of Coyote Creek" in the summer of 1868. Following a series of raids on stagecoaches and isolated ranches, a detachment from Fort Henning, led by Captain Jedediah Blake, tracked a Cheyenne war party to a bend in Coyote Creek, some twenty miles west of the fort. The ensuing engagement was fierce and bloody, lasting several hours. Though the U.S. troops eventually forced the Cheyenne to retreat, both sides suffered heavy casualties, underscoring the brutal realities of frontier warfare. A later report from Captain Blake noted, "The bravery displayed by both our men and the native warriors was beyond question. It was a fight born of desperation on both sides."

Beyond direct conflict, Fort Henning served as a critical hub for intelligence gathering and communication. Scouts, often including skilled Native American trackers from friendly tribes, would bring reports of tribal movements or the presence of hostile bands. Mail carriers, enduring perilous journeys, would deliver news from the "civilized" world, eagerly awaited by the fort’s residents. Even legendary figures like Wild Bill Hickok, who served as a scout for the army at various times, and General George Armstrong Custer, during his campaigns in the region, are said to have briefly graced its parade grounds, adding a touch of historical celebrity to its remote existence.

For the soldiers, life was often a cycle of tedium and terror. Patrols could be uneventful for weeks, only to erupt into sudden, violent encounters. The constant vigilance, the awareness of being deep within a vast and often hostile landscape, took its toll. "Every shadow held a potential threat, every distant dust cloud required scrutiny," recalled Private John Miller in a letter home, "You learned to sleep with one eye open and your rifle close at hand."

By the late 1870s, the strategic importance of Fort Henning began to wane. The frontier was rapidly moving westward, pushed by the relentless expansion of the railroads, which brought with them not only settlers but also a more efficient means of military deployment. Treaties, some more enduring than others, had been signed with various Native American tribes, reducing the frequency of large-scale conflicts. The need for isolated, static outposts like Fort Henning diminished as the military adapted to new strategies and technologies.

The order for its abandonment came in 1883. The remaining garrison packed their belongings, loaded their wagons, and marched away, leaving behind a silent testament to a bygone era. The fort’s buildings were stripped of anything valuable – timber, glass, metal – by settlers eager for building materials. The Kansas wind, which had always been a constant companion, slowly began its work of erosion, reclaiming the land.

Today, little remains of Fort Henning beyond its stone foundations, outlines of its former buildings etched into the earth, and a few scattered artifacts that occasionally surface after a heavy rain. A modest historical marker, erected by the Smoky Hill Heritage Foundation in the late 20th century, stands as a lone sentinel, offering a brief summary of the fort’s history to the rare visitor who ventures off the main roads.

"Fort Henning is more than just a collection of ruins; it is a tangible echo of a pivotal era in American history," says Dr. Eleanor Vance, a local historian and tireless advocate for the fort’s memory. "It represents the immense challenges faced by both the soldiers who manned these outposts and the indigenous peoples whose lives were irrevocably altered by their presence. It’s a reminder of the raw, often brutal, process of nation-building." Dr. Vance and the Smoky Hill Heritage Foundation have spearheaded efforts to document the fort’s layout through archaeological surveys and oral histories passed down through local families. They dream of a small interpretive center, a place where the stories of Fort Henning can be told to future generations.

The legacy of Fort Henning is not one of grand battles or famous treaties, but rather the quiet, persistent story of ordinary men facing extraordinary circumstances. It stands as a symbol of the countless small outposts that dotted the American frontier, each playing a crucial, if often unheralded, role in the shaping of a nation. These forts were the frontline of a cultural collision, places where different worlds met, often violently, but also sometimes through negotiation and adaptation.

As the Kansas wind whispers across the prairie grasses, it carries with it the spectral voices of those who lived and died at Fort Henning: the soldiers enduring the harsh elements, the officers making impossible decisions, the Native Americans defending their homeland, and the hopeful settlers pushing ever westward. While the physical structures may have crumbled, the story of Fort Henning endures, a poignant reminder that even in the most remote corners of the past, there are lessons to be learned and histories that deserve to be remembered. It is a testament to the enduring human spirit in the face of adversity, and a silent monument to the complex, often contradictory, narrative of the American West.