Fort McKenzie: Where Empire and Indigenous Worlds Collided on the Montana Frontier

The vast, untamed expanse of Montana, a land of towering peaks, sprawling plains, and mighty rivers, holds countless stories etched into its very bedrock. Many are tales of natural grandeur, others of human endurance. But few encapsulate the raw, often brutal, collision of burgeoning American empire and long-established Indigenous lifeways quite like the brief, dramatic history of Fort McKenzie. A ghost of empire, its physical remains have long vanished, reclaimed by the relentless Montana wilderness, yet its narrative echoes with the ambition, violence, and shifting allegiances that defined the American fur trade.

Nestled near the strategic confluence of the Missouri and Marias Rivers, Fort McKenzie was more than just a trading post; it was a fortress, a symbol of American commercial might pushed deep into the heart of what was, for centuries, Blackfeet territory. Its existence, though fleeting from 1832 to 1834, was marked by an event so pivotal and brutal – the Battle of Fort McKenzie – that it left an indelible scar on the landscape and the collective memory of the tribes who called this land home.

The Grand Stage: Montana’s Fur Empire

To understand Fort McKenzie, one must first grasp the immense economic and geopolitical forces at play in the early 19th century. Europe’s insatiable demand for beaver pelts, primarily for the fashioning of coveted felt hats, propelled American and British fur companies into the farthest reaches of the North American continent. The Missouri River, a serpentine highway stretching thousands of miles, became the primary artery for this commerce, carrying trade goods upriver and valuable furs back down to St. Louis, the bustling hub of the fur trade.

At the apex of this lucrative enterprise stood the American Fur Company (AFC), a colossal enterprise founded by John Jacob Astor. By the 1830s, under the formidable leadership of figures like Kenneth McKenzie, the AFC had established a near-monopoly, pushing out rivals and extending its reach deep into what is now Montana. McKenzie, known as the "King of the Missouri," was a shrewd and ruthless businessman who understood the critical importance of cultivating relationships – however precarious – with the powerful Indigenous nations who controlled the land and, crucially, the beaver supply.

The Blackfeet Confederacy, particularly the Piegan (or Pikuni) band, were the dominant power in the region where Fort McKenzie would be built. Fiercely independent and militarily formidable, they controlled prime hunting grounds and were adept traders. However, their relationship with the Americans was complex, marked by periods of trade interspersed with intense conflict, often fueled by disease, competition over resources, and misunderstandings.

It was Kenneth McKenzie who envisioned a permanent post deep within Blackfeet territory, a move that would solidify the AFC’s control over the lucrative trade with these powerful people. He chose the site carefully: a defensible position on the north bank of the Missouri, a short distance below the mouth of the Marias River. This strategic location was intended to intercept furs before they could reach rival British traders or other American companies. In 1832, under the supervision of James Kipp, a seasoned fur trader, Fort McKenzie was constructed.

A Bastion in the Wilderness: Life at the Fort

Fort McKenzie was no mere collection of cabins. It was a proper stockade, designed for defense against potentially hostile Indigenous groups and rival traders. Its walls, made of vertically set logs sharpened at the top, enclosed a central courtyard. Within this protective shell were the living quarters for the traders and engagés (French-Canadian laborers), storage facilities for trade goods and furs, and a specialized trade room where transactions took place. Bastions, projecting towers with firing slits, provided a commanding view of the surrounding landscape, offering vital defensive positions.

Life within the fort was a curious blend of monotony and sudden danger. Days were often spent in the arduous tasks of preparing furs, maintaining the fort, or waiting for the arrival of trading parties. The air would be thick with the smell of woodsmoke, tanned hides, and the pungent odor of unwashed men. Communication with the outside world was slow and infrequent, dependent on the annual steamboat or daring overland journeys.

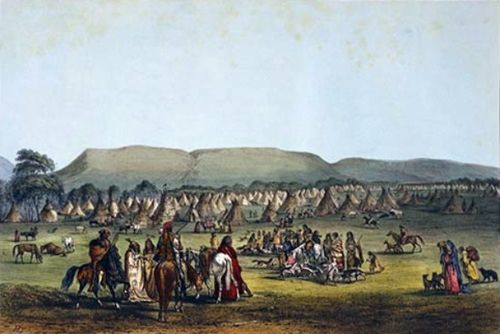

The primary purpose, of course, was trade. Indigenous groups, primarily the Piegan Blackfeet, would arrive with their meticulously prepared furs – beaver, otter, fox, and buffalo robes. In exchange, they received coveted European goods: firearms, ammunition, blankets, iron kettles, knives, beads, and tobacco. These transactions were delicate dances of diplomacy, bargaining, and mutual suspicion. The traders relied on the Indigenous peoples for their knowledge of the land and their hunting prowess, while the Indigenous peoples increasingly depended on the Europeans for manufactured goods that had become integrated into their way of life.

However, the peace was always fragile. The AFC’s presence, and its provision of firearms, inevitably exacerbated existing intertribal rivalries. The Blackfeet were frequently at war with their traditional enemies – the Crow, Assiniboine, and Cree – and the American traders often found themselves caught in the middle, or, more cynically, manipulated these tensions for their own commercial benefit. The stage was set for an explosive confrontation.

The Gathering Storm: Seeds of Conflict

By the summer of 1833, tensions around Fort McKenzie had reached a boiling point. The Blackfeet, particularly a band of Piegan who had recently been involved in raiding Assiniboine camps, were encamped in large numbers near the fort. Their presence, while providing trading opportunities, also brought an air of unease. They were powerful, proud, and often unpredictable.

Meanwhile, a large war party of Assiniboine and Cree, numbering several hundred warriors, was approaching the fort from downriver. They were on a mission of revenge against the Blackfeet for recent attacks and horse thefts. Crucially, the Assiniboine were also key trading partners of the American Fur Company, and their alliance with the company was strong.

Inside Fort McKenzie, David D. Mitchell, a young but capable clerk for the AFC, found himself in an unenviable position. He knew that if the two tribal groups met outside the fort, a bloody battle was inevitable, one that could disrupt trade and potentially endanger the fort itself. He also understood the AFC’s long-standing policy: maintain good relations with all trading partners, but protect company interests at all costs.

Mitchell decided to act. He met with the leaders of the approaching Assiniboine and Cree, effectively striking a deal. If they would attack the Blackfeet while they were vulnerable, encamped near the fort, the AFC would provide them with support – specifically, with the firepower of the fort’s cannon and rifles. It was a calculated, cold-blooded decision, designed to protect the fort’s interests by using one Indigenous group to weaken another.

The Battle of Fort McKenzie: A Day of Blood

The morning of August 26, 1833, dawned clear and deceptively peaceful. Hundreds of Piegan Blackfeet warriors, along with their families, were camped directly outside Fort McKenzie, some trading, others preparing for the day. Inside the fort, Mitchell and his men, along with the allied Assiniboine and Cree warriors, were making their final preparations.

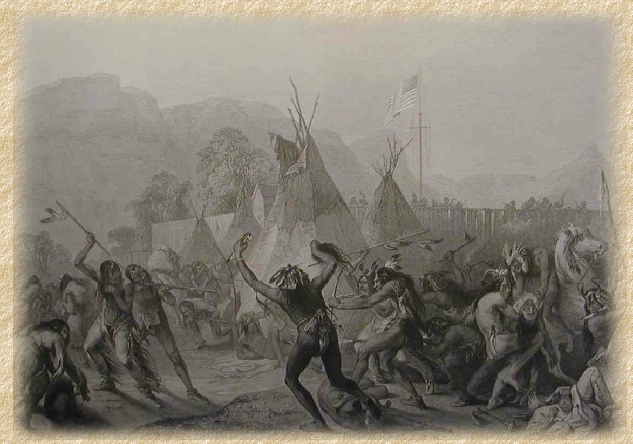

Suddenly, the silence was shattered. The Assiniboine and Cree, bursting from the cover of the riverbanks and ravines, launched a ferocious, coordinated assault on the unsuspecting Blackfeet camp. War cries echoed across the plains as the allied warriors surged forward, armed with bows, lances, and the firearms provided by the traders.

From the bastions of Fort McKenzie, Mitchell and his men opened fire, not with muskets, but with the fort’s cannon, blasting grape-shot and canister into the dense Blackfeet encampment. The roar of the cannon, a terrifying sound to those who had never heard it in battle, added to the chaos and devastation. "The cannon," as one contemporary account noted, "made dreadful havoc." The coordinated attack caught the Blackfeet completely by surprise.

The battle was swift, brutal, and utterly devastating for the Piegan. Caught between the attacking warriors and the fire from the fort, many had little chance to defend themselves or escape. Warriors fought valiantly, but the combined force was overwhelming. The fighting was hand-to-hand in many places, a maelstrom of violence, screaming, and the acrid smell of gunpowder.

By the time the fighting subsided, the Blackfeet camp was a scene of carnage. Estimates vary, but between 30 and 40 Blackfeet warriors were killed, many more wounded, and their camp was plundered and destroyed. The victors, emboldened by their success and the support of the fort, engaged in the grisly practice of scalping and mutilation, a stark and horrifying testament to the brutality of frontier warfare.

The American Fur Company men watched, and participated, in the massacre, their actions forever cementing the fort’s dark reputation. The Battle of Fort McKenzie was not merely an intertribal skirmish; it was a deliberate intervention by American commercial interests, leveraging Indigenous conflict for their own strategic gain.

Aftermath and Legacy

In the immediate aftermath, the balance of power in the region shifted dramatically. The Blackfeet, though severely chastised, were far from broken, but their confidence and dominance had been shaken. For a time, trade at Fort McKenzie continued, now with a clearer understanding of the AFC’s willingness to use force to maintain its position. David D. Mitchell, despite his controversial actions, was lauded by his superiors for his decisiveness and for securing the company’s interests. He would go on to have a distinguished career, eventually becoming Superintendent of Indian Affairs for the Central Superintendency.

However, the days of Fort McKenzie were numbered. The fur trade, like all resource booms, was inherently unsustainable. By the mid-1830s, the beaver population had been decimated by relentless hunting. Furthermore, changing European fashions, particularly the rising popularity of silk hats over beaver felt, dealt a fatal blow to the industry.

By 1834 or 1835, Fort McKenzie was abandoned. Its strategic purpose had evaporated, and its economic viability was gone. The AFC consolidated its operations at other posts, but the grand era of the beaver pelt was drawing to a close. The wilderness, patient and relentless, began to reclaim the site. Logs rotted, stockades collapsed, and the ground softened, erasing almost all physical trace of the brief, violent outpost.

Today, there is little to see at the precise location of Fort McKenzie. No majestic ruins stand as a testament to its dramatic past. The Missouri River still flows, the Marias still joins it, and the vast Montana sky still arches overhead. Yet, for those who know its story, the echoes of that fateful day in August 1833 remain. Fort McKenzie serves as a poignant, if grim, reminder of a pivotal moment in American history – a time when the relentless pursuit of profit, the complex and often tragic interactions between Indigenous nations and European powers, and the raw