Fort Michilimackinac: Where Empires Collided and History Echoes

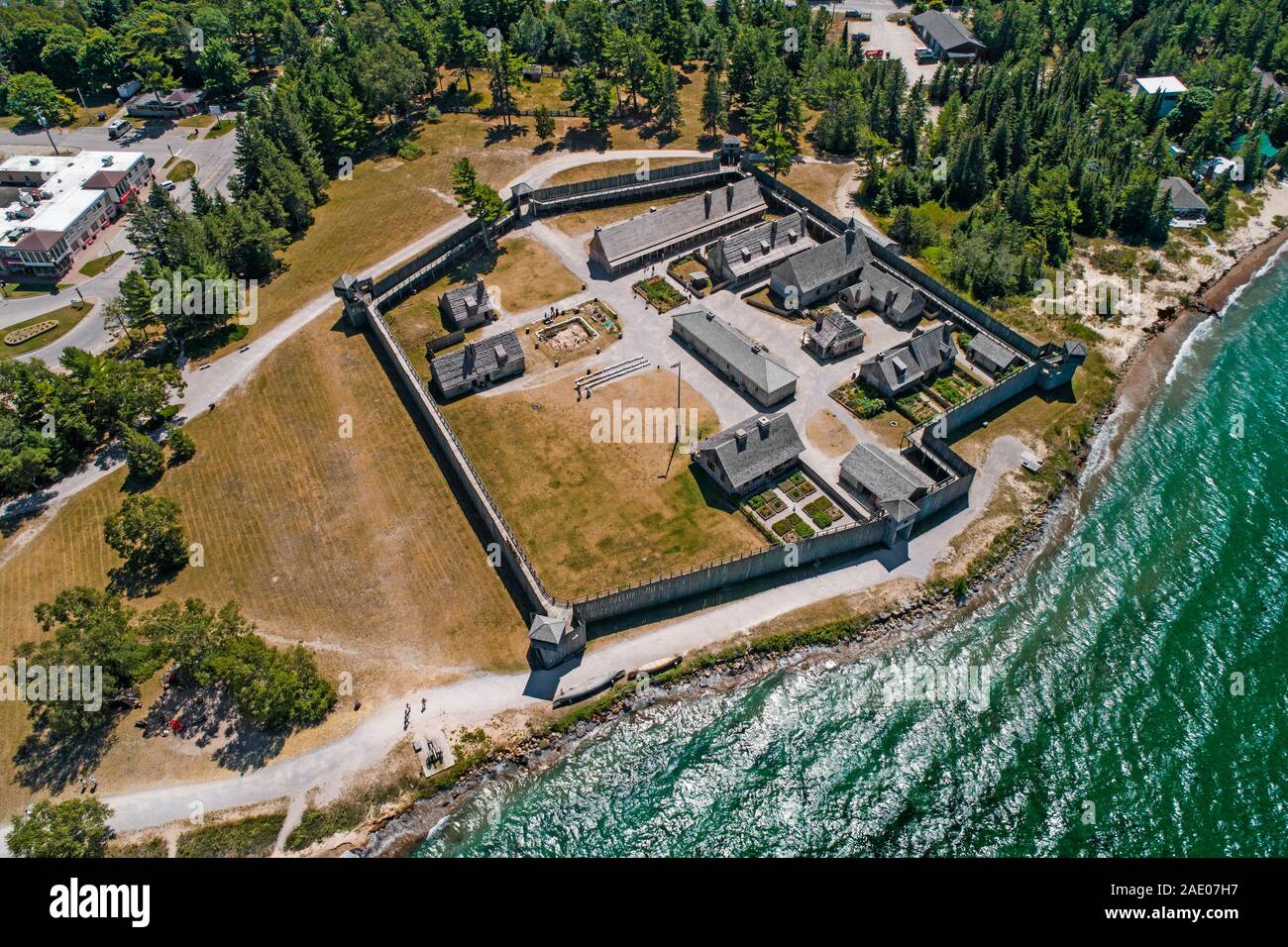

At the narrowest point of the Straits of Mackinac, where Lake Huron and Lake Michigan converge, stands Fort Michilimackinac. It’s more than just a collection of reconstructed palisades and period buildings; it’s a meticulously preserved portal to a tumultuous past, a place where the destinies of three empires – French, British, and Native American – dramatically intertwined. For those who walk its grounds today, the whispers of history are almost palpable, carried on the lake breeze that once filled the sails of fur-laden canoes and the air with the cries of battle.

Fort Michilimackinac, located in what is now Mackinaw City, Michigan, was not just a military outpost; it was a bustling, multicultural community that served as a vital hub for the North American fur trade from the early 18th century until its abandonment during the American Revolution. Its strategic location, commanding the vital waterway connecting the Great Lakes, made it a coveted prize, a crossroads of cultures, commerce, and conflict.

The French Genesis: A Fur Trade Empire

The story of Michilimackinac begins with the French. By the late 17th century, France had established a vast, albeit thinly populated, empire stretching from Quebec down the Mississippi River to New Orleans. Central to this empire was the lucrative fur trade, particularly beaver pelts, which were highly prized in Europe for hat making. To protect their trade routes, solidify alliances with Native American tribes, and project their influence, the French established a series of forts.

Around 1715, a permanent French stockaded fort was constructed at Michilimackinac, replacing earlier, less permanent posts in the region. This new fort, originally known as Fort de Buade or Michilimackinac, quickly became the primary transshipment point for furs traveling from the interior of the continent to Montreal. Here, Native American trappers, primarily Odawa and Ojibwe, exchanged beaver, otter, and fox furs for European goods: iron tools, firearms, blankets, glass beads, and brandy.

Life within the French fort was a vibrant tapestry of cultures. French soldiers, fur traders (known as voyageurs), craftsmen, and Jesuit missionaries lived alongside their Native American allies, many of whom had intermarried with the French. French was the dominant language, but Algonquin dialects, particularly Odawa, were widely spoken. The Jesuit mission, with its chapel, played a significant role, attempting to convert the Native population while also serving as a spiritual center for the French inhabitants.

"Michilimackinac was a microcosm of New France," explains historian Dr. Brian Leigh Dunnigan, curator emeritus of maps and director emeritus of the Clements Library at the University of Michigan, who has extensively studied the fort. "It was a place where commercial interests, military strategy, and cultural exchange converged, often with fascinating and complex results."

The British Ascendancy and Pontiac’s Rebellion

The mid-18th century brought a dramatic shift in power. The escalating rivalry between France and Great Britain culminated in the French and Indian War (1754-1763), a global conflict known in Europe as the Seven Years’ War. After a series of devastating defeats, France ceded its North American territories east of the Mississippi to Great Britain in the Treaty of Paris (1763).

With the stroke of a pen, Fort Michilimackinac, along with other French outposts, passed into British hands. The transition was not smooth. The British, with their more rigid approach to trade and their often dismissive attitude towards Native American customs and alliances, quickly alienated many of the tribes who had long-standing relationships with the French. British policies, such as halting the traditional gifting of goods and restricting access to gunpowder, fueled resentment.

This discontent ignited in the spring of 1763, when Pontiac, an Ottawa war chief, orchestrated a widespread Native American uprising against British forts throughout the Great Lakes region and Ohio Valley. Fort Michilimackinac was among the targets.

On June 2, 1763, the Ojibwe, led by Chief Minavavana, launched a surprise attack on the fort. They used a ruse: a seemingly innocent game of baggataway (a precursor to lacrosse) played outside the fort’s gates, involving both Ojibwe and some Sauk warriors. The British garrison, unsuspecting, watched the spirited game. Suddenly, the ball was intentionally hit over the fort’s palisades. When the warriors rushed in to retrieve it, they seized hidden weapons – tomahawks and knives – that Native women had smuggled under their blankets.

The ensuing massacre was swift and brutal. British soldiers, caught off guard, were overwhelmed. The harrowing account of Alexander Henry, a British fur trader who survived the attack by hiding in a local merchant’s attic, provides a chilling eyewitness perspective. "I saw," he wrote, "upwards of a hundred dead bodies, heaped up in a small compass, and the ground covered with blood." Of the 35-man British garrison, 15 were killed immediately, and five more were later executed. The fort was occupied by the Ojibwe and their allies for several months before British forces eventually reoccupied it.

The events of 1763 profoundly impacted the British perspective on Native American relations and highlighted the precariousness of their hold on the frontier. It also serves as a stark reminder of the complex and often violent encounters that shaped early North America.

The British Era and the Fort’s Demise

Following Pontiac’s Rebellion, the British strengthened Michilimackinac, reinforcing its defenses and maintaining it as a vital fur trade post. Life within the fort resumed its rhythm, albeit with a heightened sense of vigilance. British soldiers, Scottish merchants, and Native American families continued to interact, trade, and sometimes clash. The fort remained a melting pot, though the power dynamics had shifted irrevocably.

However, the dawn of the American Revolution (1775-1783) presented new challenges. Michilimackinac, built primarily of wood and vulnerable to cannon fire from the surrounding bluffs, was deemed indefensible against a potential American attack. In 1779, British Lieutenant Governor Patrick Sinclair began construction of a new limestone fort on the much more defensible Mackinac Island, a few miles east in the Straits. By 1781, Fort Michilimackinac was entirely dismantled, its timbers and materials ferried across the water to construct the new Fort Mackinac. The old fort, which had stood for over six decades as a symbol of colonial ambition and frontier life, was abandoned to the elements.

Rebirth Through Archaeology: A Living Classroom

For nearly 150 years, the site of Fort Michilimackinac lay forgotten, slowly reclaimed by nature. Its existence was known, but its exact layout and the rich stories buried beneath the soil remained largely hidden. It was not grand monuments that led to its rebirth, but the painstaking work of archaeologists.

Beginning in 1959, and continuing almost every summer since, archaeological excavations at Fort Michilimackinac have systematically unearthed the fort’s foundations, structures, and an astonishing wealth of artifacts. The Mackinac State Historic Parks, which manages the site, has spearheaded this remarkable effort, making Michilimackinac one of the longest continuously running archaeological projects in North America.

"Every shovel full of dirt can tell a story," says Dr. Lynn Evans, Curator of Archaeology for Mackinac State Historic Parks. "We’ve recovered literally millions of artifacts – pipes, buttons, tools, fragments of ceramics, military accoutrements, personal items – that paint an incredibly detailed picture of daily life here. We can tell you what people ate, what they wore, what their homes looked like, even what games they played."

These archaeological discoveries have formed the bedrock of the fort’s reconstruction. Rather than relying on guesswork, the buildings and palisades visitors see today are meticulously recreated based on irrefutable archaeological evidence and historical documents. This commitment to authenticity makes Fort Michilimackinac unique, transforming it from a mere historical site into a living laboratory where history is not just recounted but actively re-discovered and re-presented.

Experiencing History Today: A Walk Through Time

Today, Fort Michilimackinac offers an immersive experience unlike any other. Stepping through its gates is akin to traveling back in time to the 1770s. Costumed interpreters, portraying soldiers, traders, artisans, and Native Americans, bring the fort to life. They demonstrate daily chores, fire muskets and cannons, cook over open hearths, and engage visitors in conversations about the challenges and triumphs of frontier life.

Visitors can explore the commander’s house, the soldiers’ barracks, the church, the storehouses, and the various homes and workshops that once lined the fort’s narrow streets. The smell of woodsmoke, the crack of a musket, the distant sound of waves, and the sight of interpreters going about their "daily lives" combine to create a deeply engaging and educational experience.

Beyond the living history, the fort also houses exhibits showcasing some of the remarkable archaeological finds, providing context and deeper insight into the artifacts that have literally shaped its reconstruction. The interpretive center offers background on the fur trade, the different cultures that inhabited the fort, and the dramatic events that unfolded here.

Fort Michilimackinac stands as a silent sentinel, guarding the Straits and the stories of those who lived and died within its walls. It reminds us that North America’s past is a complex tapestry woven from many threads – of exploration and exploitation, cooperation and conflict, trade and survival. It is a place where empires clashed, where cultures mingled, and where the echoes of a distant past continue to resonate, inviting us to listen, learn, and reflect on the enduring human drama played out on this historic stage.