Fort Solomon: Echoes of a Forgotten Frontier Bastion in Kansas

The vast, undulating prairies of Kansas hold countless stories, whispered on the wind, etched into the landscape, and often, tragically, lost to the relentless march of time. Among these fading echoes is the tale of Fort Solomon, a name that, for many, evokes little recognition, yet once stood as a vital, if humble, bastion on the raw edge of the American frontier. Built not by federal decree, but by the desperate hands of settlers caught between the brutal realities of the Civil War and the volatile dynamics of westward expansion, Fort Solomon stands as a stark testament to the resilience, fear, and tenacity of those who dared to call this challenging land home.

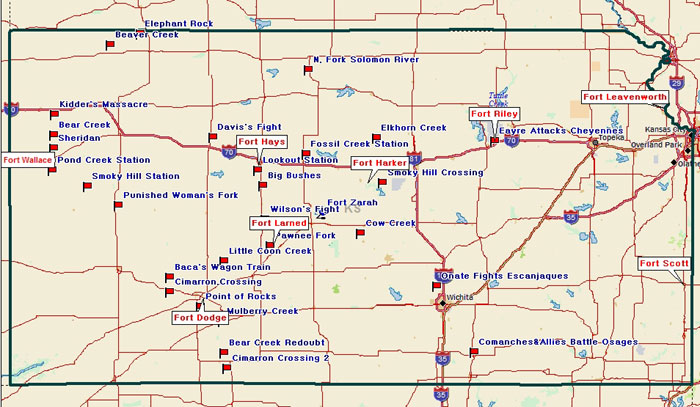

Today, nothing remains of the original Fort Solomon but a historical marker near the confluence of the Smoky Hill and Solomon Rivers, a silent sentinel to a past that shaped Kansas. Its physical absence, however, belies its profound significance. To understand Fort Solomon, one must first understand the Kansas of the mid-19th century—a land synonymous with "Bleeding Kansas," a crucible of conflict even before the shots at Fort Sumter.

A Land in Turmoil: The Genesis of Necessity

Kansas in the 1850s and 1860s was a political and social tinderbox. The Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 ignited a brutal proxy war between pro-slavery and anti-slavery factions, each vying for control of the territory’s destiny. This internal strife, characterized by raids, massacres, and constant fear, set the stage for a unique brand of frontier insecurity. When the Civil War erupted in 1861, Kansas, having finally been admitted to the Union as a free state, found its internal divisions amplified and its meager resources stretched thin. Federal troops were largely occupied with the war against the Confederacy, leaving vast swathes of the frontier vulnerable.

It was into this volatile vacuum that the need for local, self-made defenses arose. Settlers pushing westward, often seeking new lives free from the entrenched societal norms of the East, found themselves isolated and exposed. They faced not only the lingering threat of Confederate sympathizers and raiders from Missouri but also the escalating tensions with Native American tribes—the Kansa, Pawnee, Cheyenne, and Sioux—who viewed the encroaching settlers as an existential threat to their ancestral lands and way of life. The U.S. government, preoccupied with the larger conflict, could offer little immediate protection to these far-flung pioneers.

The Birth of a Civilian Bastion

In this atmosphere of pervasive anxiety, the settlers of the newly forming communities along the Solomon and Smoky Hill river valleys took matters into their own hands. In the spring of 1864, a group of determined pioneers, led by local figures and volunteers, began construction on what would become Fort Solomon. Its location was strategically chosen near the confluence of the two rivers, providing access to water and a relatively defensible position.

"Fort Solomon was less a military stronghold and more a collective sigh of relief for those trying to carve out a life on the Kansas frontier," explains Dr. Evelyn Reed, a historian specializing in frontier Kansas. "It was a testament to community self-reliance in an era where the government couldn’t always be there."

Unlike the grand, masonry forts built by the U.S. Army, Fort Solomon was a humble affair. It was constructed primarily of cottonwood logs, cut from the riverbanks, and earthworks. Accounts suggest it was a rectangular stockade, perhaps with blockhouses at the corners, designed to offer rudimentary protection against raids. It wasn’t meant to withstand a prolonged siege by a large army, but rather to serve as a refuge for families, their livestock, and their meager possessions during times of immediate danger. The work was arduous, undertaken by men, women, and even children, who understood that their survival depended on its completion.

Dual Threats: Rebels and Raiders

The primary threats that necessitated Fort Solomon’s existence were two-fold. Firstly, there was the lingering fear of Confederate incursions. While Kansas was a Union state, it bordered Missouri, a deeply divided state where pro-Confederate bushwhackers and guerrillas, like William Quantrill, frequently launched devastating raids into Union territory. The memory of the Lawrence Massacre in 1863, where Quantrill’s raiders burned the town and killed over 150 men and boys, sent shivers down the spines of every Kansas settler. Though Fort Solomon was far west of the main theater of these raids, its isolation made it a tempting target for smaller, opportunistic bands.

Secondly, and perhaps more consistently, there was the threat of Native American conflicts. As settlers pushed further west, they encroached upon the hunting grounds and traditional territories of various Plains tribes. The U.S. government’s policies of forced removal and broken treaties fueled resentment and retaliatory raids. While some interactions were peaceful, the perception of danger was constant, and isolated homesteads were particularly vulnerable. Fort Solomon offered a centralized point of defense and a place to muster local militia in response to perceived threats or actual attacks on settlers or supply lines.

"We built it with our own hands, every log, every shovel of earth, because we knew no one else would protect us out here," a hypothetical pioneer might have recounted, echoing the sentiments of the time. The fort became a symbol of their collective will to survive and thrive against overwhelming odds.

A Hub of Frontier Life

Beyond its defensive role, Fort Solomon also served as a small hub for the nascent communities. It provided a sense of security that encouraged further settlement in the surrounding valleys. It was a place where mail might be dropped, news exchanged, and where the Butterfield Overland Despatch, a vital stagecoach and mail service connecting the East with the West, might find a measure of safety along its arduous route. The fort’s presence, though small, was a crucial node in the fragile network of communication and transportation that knit the sprawling frontier together.

Despite the constant threats, Fort Solomon itself never saw a major battle or a grand assault. Its strength lay not in its impregnability, but in its very existence—a deterrent that signaled to potential raiders that these settlers were organized and prepared to defend themselves. This passive defense was, in many ways, its greatest triumph. Its construction and continued operation represented the psychological fortitude of the pioneers.

The Waning of a Watchtower

Fort Solomon’s active life was relatively brief, a reflection of the rapidly changing dynamics of the frontier. By the end of the Civil War in 1865, the immediate threat of Confederate incursions vanished. Federal military strategy also shifted. With the Union secured, the U.S. Army began to establish larger, more permanent forts further west, like Fort Hays and Fort Wallace, to project power and manage relations with Native American tribes on a broader scale.

As these larger military outposts took over the role of frontier defense, and as more settlers poured into Kansas, creating larger, more established towns like nearby Salina, the immediate need for small, civilian-built forts like Solomon diminished. Its logs, once painstakingly cut and erected, were likely repurposed for homes, barns, or fences as the surrounding area transitioned from a wild frontier to a more settled agricultural landscape. The fort simply faded into the landscape, its purpose served, its memory gradually absorbed by the very prairie it once guarded.

Legacy of the Forgotten Fort

Today, Fort Solomon exists primarily in the annals of local history and as a point on a map marked by a modest sign. Yet, its story resonates with profound lessons about American expansion, self-reliance, and the brutal costs of nation-building. It reminds us that the frontier was not just shaped by grand military campaigns and political decrees, but by the everyday courage of ordinary people.

"Its very existence, though largely forgotten by the national narrative, speaks volumes about the tenacity of early American pioneers," observes local historian Mark Thompson. "These small forts were the lifeblood of their communities, a physical manifestation of their refusal to surrender to the overwhelming challenges of the West."

Fort Solomon is a quiet monument to the pioneers who built it, defended it, and ultimately outgrew it. It stands as a powerful symbol of the American spirit: the willingness to face adversity, to organize for common defense, and to carve out a future from the unforgiving wilderness. While no walls remain, the echoes of its purpose—protection, resilience, and community—continue to reverberate through the Kansas plains, a timeless reminder of a vital, yet largely unheralded, chapter in the story of the American West. The next time you pass a historical marker in a quiet field, remember that beneath the surface, a story as rich and compelling as that of Fort Solomon awaits discovery, waiting for the wind to whisper its forgotten truths once more.