Fort Yuma: Where Empires Collided on the Sun-Baked Frontier

The Colorado River, a lifeline carving its way through the stark beauty of the Sonoran Desert, has always been a place of immense power and strategic significance. For millennia, its banks nurtured the Quechan people, whose ancient dominion over its only reliable crossing point made them arbiters of passage. Then came the Americans, propelled by a feverish gold rush and an unshakeable belief in Manifest Destiny. In this sun-baked crucible, on a bluff overlooking the river, Fort Yuma rose – a silent sentinel to a tumultuous era where cultures clashed, destinies diverged, and the very fabric of a nation was forged.

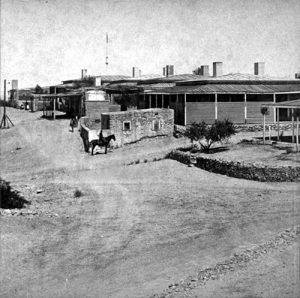

Today, the original site of Fort Yuma, nestled on the California side of the river and now part of the Quechan Indian Reservation, stands as a quiet monument to this complex past. Its remaining adobe structures, weathered by time and the relentless desert sun, whisper tales of soldiers battling not just indigenous resistance but also the brutal elements, of pioneers seeking fortune, and of a resilient people fighting for their ancestral lands. It is a place where history isn’t just read in books; it’s felt in the dry air, seen in the vast horizon, and understood in the enduring presence of the Quechan.

The Strategic Imperative: A River, A Crossing, A Gold Rush

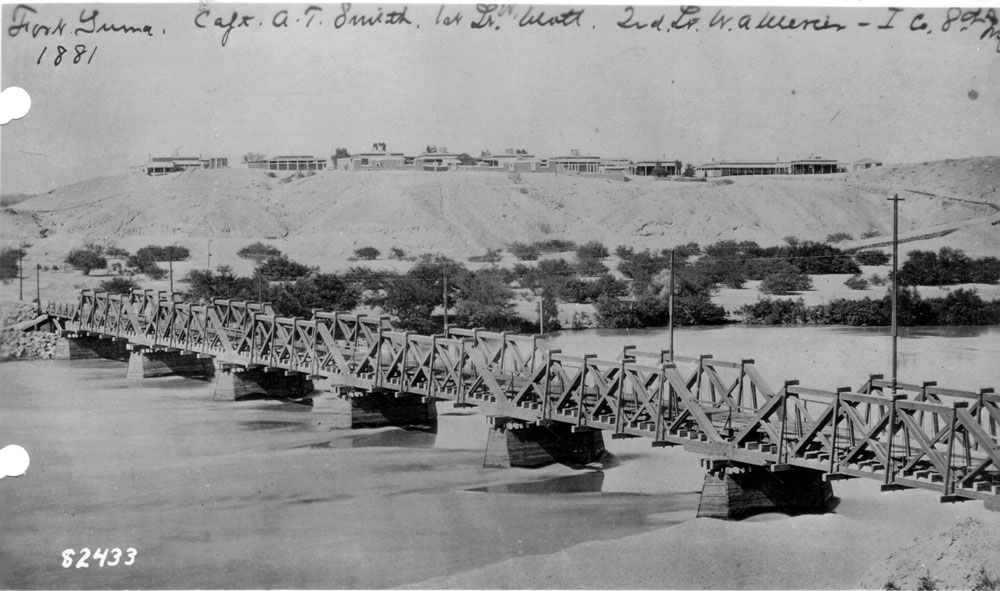

The story of Fort Yuma begins not with a military decree, but with geography. For hundreds of miles, the Colorado River presented an impassable barrier to overland travel. But at a narrow gorge where the Gila River joined the Colorado, a natural ford and ferry crossing existed – a vital bottleneck for anyone traversing the desert Southwest. This "Yuma Crossing" was, as historian Robert L. Spude noted, "the only practical route between California and the East."

When news of gold in California exploded in 1848, the trickle of westward migration became a torrent. Thousands of fortune-seekers, many ill-prepared, poured across the continent, their eyes fixed on the promise of riches. The Yuma Crossing became a chokepoint of epic proportions, a scene of desperate human ambition. The Quechan, who had controlled and managed this crossing for centuries, quickly understood its new value. They operated a ferry, levied tolls, and often traded with or aided the weary travelers. However, the sheer volume of migrants, coupled with their often-disrespectful attitudes and the inevitable conflicts over resources, quickly strained relations to a breaking point.

The U.S. government, having recently acquired vast territories from Mexico through the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, recognized the strategic imperative of controlling this vital artery. The existing ferry operation by the Quechan, while efficient, was seen as a potential impediment to American expansion. Military control was deemed essential to protect American citizens, secure supply lines, and assert federal authority over the new frontier.

The Birth of the Fort and the Yuma War

In November 1850, after an initial, short-lived encampment, the U.S. Army formally established Fort Yuma on a mesa overlooking the strategic crossing. Its mission was clear: protect the ferry, guard the emigrant trail, and, perhaps most importantly, "pacify" the Quechan people. For the Quechan, led by their influential chief, Salvador Palma, the fort was an unwelcome intrusion, a direct challenge to their sovereignty and their traditional way of life.

The tensions quickly escalated into open conflict. The so-called "Yuma War" of 1851-1852 saw the Quechan, allied with other local tribes, resist the American presence with fierce determination. They harassed emigrant trains, attacked the fort, and sought to reclaim their ancestral lands and control over the river. One officer, reflecting on the hostile environment, reportedly described a posting to Fort Yuma as akin to "being exiled to hell."

Despite their courage and superior knowledge of the unforgiving terrain, the Quechan were ultimately outmatched by the U.S. Army’s superior firepower and organization. The war resulted in significant losses for the Quechan and the eventual consolidation of American power at the crossing. The fort, though never truly impregnable, served its purpose, becoming a powerful symbol of American might in the desert.

Life in the Hellhole: A Soldier’s Burden

Life for the soldiers stationed at Fort Yuma was a relentless test of endurance. The desert climate was unforgiving, with summer temperatures routinely soaring past 120 degrees Fahrenheit, making it, as one contemporary account described, "a veritable hellhole." The heat, dust, and scarcity of fresh water were constant adversaries. Disease, particularly malaria and dysentery, was rampant, taking a heavier toll than any battle.

"The sun beats down with a fury that saps one’s very will to live," wrote a despondent private in a letter home, "and the dust chokes you until you can barely breathe. Every day is a struggle against the elements, and against the crushing monotony." Isolation was another significant challenge. Supplies had to be brought in by steamboat up the treacherous Colorado River, or by wagon train across vast, hostile stretches of desert. Mail was infrequent, and the nearest substantial settlement was hundreds of miles away. Desertion rates were high, reflecting the harsh realities of service.

Yet, despite these extreme conditions, the soldiers of Fort Yuma performed their duties. They patrolled the trails, guarded the ferry, and engaged in skirmishes with various Native American groups. They built and maintained the fort’s adobe structures, some of which still stand today, a testament to their labor and resilience. The fort also played a crucial role during the American Civil War, serving as a key supply depot for Union forces operating in the Southwest and preventing Confederate incursions into California.

A Crossroads of Cultures: Uneasy Coexistence

While Fort Yuma was a military outpost, it was also a dynamic cultural crossroads. The presence of the fort profoundly impacted the Quechan people, forcing them into an uneasy coexistence with the encroaching American culture. The fort brought not only conflict but also new forms of interaction. Quechan individuals often found employment at the fort, serving as scouts, laborers, and guides, using their intimate knowledge of the land to earn wages and adapt to the changing world.

"Our people had always been here," explained a Quechan elder in a modern interview, reflecting on the era, "and suddenly, there were these soldiers, with their uniforms and their guns. It was a shock, a challenge. But we are survivors. We learned to live with them, to work with them, even when we didn’t agree with what they were doing to our land."

The fort facilitated trade, bringing new goods and technologies, but also new diseases and social disruptions. It became a hub where different worlds collided – the ancient ways of the Quechan, the relentless ambition of American pioneers, and the stern discipline of the U.S. Army. This interaction, though often fraught with tension, also led to a degree of mutual understanding and, at times, even respect. Officers like George Crook, who served at Fort Yuma, gained valuable insights into Native American cultures, which later informed his strategies in other campaigns.

Decline and Transformation: From Fort to Mission

Fort Yuma’s strategic importance, though profound for a time, was ultimately fleeting. The advent of the transcontinental railroad, pushing westward across the continent, rapidly rendered river traffic and isolated desert forts obsolete. With the completion of the Southern Pacific Railroad in 1877, bypassing the need for the arduous Yuma Crossing, the fort’s primary reason for existence vanished. The iron horse, with its speed and efficiency, signaled the end of an era.

In 1883, the U.S. Army officially abandoned Fort Yuma. Its military function complete, the property was transferred to the Department of the Interior and subsequently to the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA). In a remarkable turn of events, the site that once symbolized American military assertion over the Quechan people became, in 1886, the home of the St. Thomas Indian Mission, established by the Catholic Church. The old adobe barracks and officers’ quarters were repurposed, serving as a school, a church, and living quarters for the Quechan children and the missionaries.

This transformation was deeply symbolic. The physical structures of the fort, once instruments of control, became tools for education and spiritual guidance, albeit within the context of forced assimilation policies common at the time. The mission played a significant role in the lives of the Quechan people for decades, educating generations and preserving aspects of their community life even as it sought to integrate them into mainstream American society.

An Enduring Legacy: Resilience and Remembrance

Today, the original site of Fort Yuma, overlooking the shimmering Colorado River, is part of the Quechan Indian Reservation and home to the St. Thomas Indian Mission and the Quechan Tribal Museum. The remaining adobe buildings, including the old officers’ quarters, stand as a testament to its layered history. Visitors can walk the grounds, feel the weight of the past, and reflect on the myriad stories etched into this sun-baked land.

Fort Yuma represents more than just a military outpost; it is a microcosm of America’s westward expansion – a story of ambition, conflict, resilience, and transformation. It reminds us of the immense human cost of progress, the clash of civilizations, and the enduring spirit of indigenous peoples. The Quechan, who have survived centuries of change, continue to thrive on their ancestral lands, their culture woven into the very fabric of this powerful landscape.

The legacy of Fort Yuma is not merely about soldiers and battles, but about the profound impact of a pivotal moment in history on all who lived it. It stands as a powerful reminder that history is never simple, and that even in the most desolate corners of the frontier, human dramas of epic proportion played out, shaping the nation we know today. As the desert sun sets over the Colorado River, casting long shadows over the fort’s ancient walls, one can almost hear the echoes of a distant past – a testament to a place where empires collided, and the American West truly began.