Frank Hamer: The Quiet Legend Who Hunted Down Bonnie and Clyde

By [Your Name/Journalist Name]

The names Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow echo through American history, synonymous with an era of desperation, rebellion, and high-speed crime. Their reign of terror, a brutal, romanticized spree across the American South and Midwest during the Great Depression, captivated a nation weary of hardship. But behind the sensational headlines and the public’s morbid fascination with the outlaw lovers stood a man whose quiet resolve and relentless pursuit ultimately brought their bloody saga to an end: Frank Hamer, a Texas Ranger whose legend was forged long before he ever set his sights on the infamous duo.

Frank Augustus Hamer was no ordinary lawman. Born in 1884 in Fairview, Texas, he was a product of a rugged, untamed frontier that was slowly giving way to modernity. His life story reads like a classic Western, a testament to an era when justice was often swift and delivered by men of extraordinary courage. Hamer’s career in law enforcement spanned over four decades, during which he faced down murderers, captured bank robbers, battled the Ku Klux Klan, and survived an astonishing 17 gunshot wounds, accumulating a reputation as one of the most effective and fearless peace officers in American history.

Hamer’s journey into the world of law enforcement began early. After a brief stint as a blacksmith, he joined the Texas Rangers in 1906, drawn to the call of duty in a state still grappling with lawlessness. From the start, Hamer distinguished himself not with bravado, but with a methodical approach and an unyielding commitment to justice. He was a man of few words, known for his stoic demeanor and piercing blue eyes that missed nothing. "He was a man who looked like he could do whatever needed to be done," legendary Texas Ranger historian Walter Prescott Webb once wrote, "and he usually did it."

His early career was a crucible. Hamer served in some of the most volatile regions of Texas, from the oil boom towns rife with vice and violence to the lawless stretches of the U.S.-Mexico border. He earned a reputation for his hard-bitten efficiency and his ability to disarm dangerous situations with a quiet authority that belied his deadly capabilities. He was involved in countless gunfights, often emerging wounded but always victorious. It’s said that his presence alone often quieted potential riots, giving rise to the famous, if apocryphal, saying, "One Riot, One Ranger" – a phrase that, while not directly attributed to Hamer, perfectly encapsulates the formidable reputation of the force he embodied.

One of Hamer’s lesser-known but equally significant achievements came during the 1920s when he took on the Ku Klux Klan. At a time when the Klan exerted considerable political and social influence, Hamer fearlessly confronted their activities, breaking up their gatherings and arresting their members, often at great personal risk. This period solidified his image as a man who would not bend to intimidation, no matter how powerful the adversary.

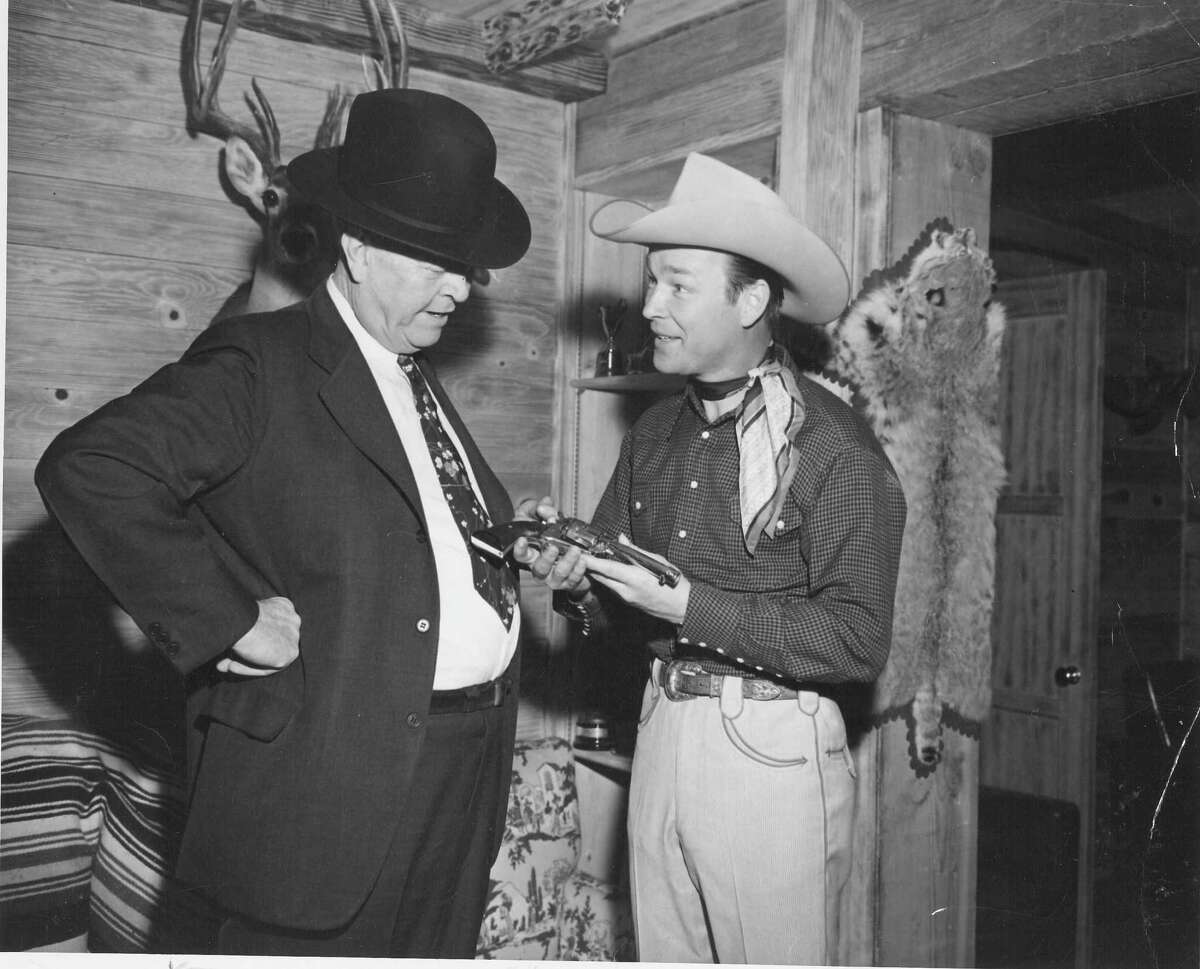

By the early 1930s, Frank Hamer had retired from the Texas Rangers, though his reputation as an indomitable lawman persisted. He was running a private security business and enjoying a quieter life with his family when the call came that would forever etch his name into the annals of American crime history.

The year was 1934. Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow, along with their various associates, had escalated their crime spree into a brutal killing rampage. They had murdered at least 13 people, including several law enforcement officers, across multiple states. Their brazen escapes, coupled with the sensational media coverage, had made them folk heroes to some, yet a terrifying menace to the authorities. Law enforcement agencies across the country were frustrated, unable to corner the elusive gang. The public was gripped by fear and outrage.

It was then that Lee Simmons, the head of the Texas Prison System, a man who had narrowly escaped a Bonnie and Clyde ambush himself, turned to the one man he believed could bring them down: Frank Hamer. Simmons reportedly offered Hamer a "retirement" that would pay him well, along with the promise of "no holds barred" in his pursuit. Hamer, despite being 50 years old and having officially retired, accepted the assignment without hesitation. He wasn’t reinstated as a Ranger but was commissioned as a special investigator for the prison system, effectively given a blank check to hunt down the outlaws.

Hamer’s approach was starkly different from the frantic, uncoordinated efforts that had failed before him. He didn’t chase after every tip or follow every lead in a reactive manner. Instead, he employed a methodical, almost academic strategy. He studied their patterns, their movements, their family connections, and their habits. He recognized that Bonnie and Clyde were creatures of habit, always returning to specific locations or family members. He understood their need for freedom and their reliance on a few trusted individuals. "He understood the criminal mind," historian John Neal Phillips noted in his book, "Running with Bonnie and Clyde." "He knew they would make a mistake eventually, and he would be there to capitalize on it."

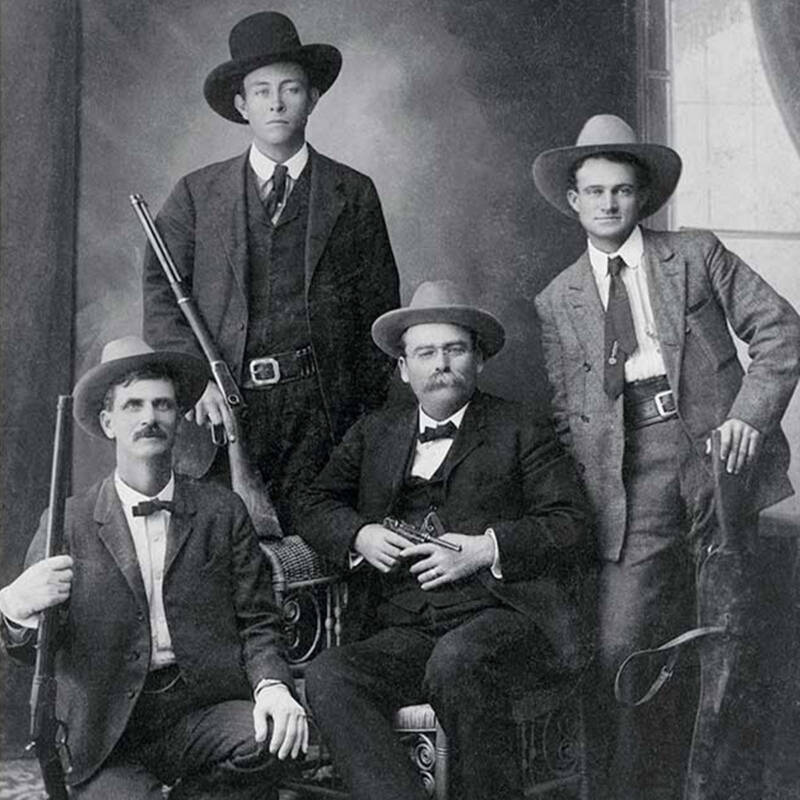

Hamer assembled a small, hand-picked team for the manhunt. It included fellow Texas Ranger Benjamin Maney Gault, Dallas County Deputy Sheriff Bob Alcorn, Dallas County Deputy Sheriff Ted Hinton, Bienville Parish Sheriff Henderson Jordan, and Bienville Parish Deputy Prentiss Oakley. This diverse group brought a mix of local knowledge and seasoned experience to the pursuit.

For months, Hamer and his team crisscrossed state lines, relentlessly tracking the gang. They followed their trail through Texas, Oklahoma, Louisiana, and Arkansas. The pursuit was a chess game, with Hamer anticipating their moves and closing in. He famously predicted that Bonnie and Clyde would eventually return to Bienville Parish, Louisiana, to visit the father of gang member Henry Methvin, a location they had used as a safe haven before.

On May 23, 1934, Hamer’s meticulous planning culminated in a dense stretch of road near Gibsland, Louisiana. Acting on intelligence that Bonnie and Clyde were due to meet Methvin’s father, the six-man posse set up an ambush in the early hours of the morning. They waited patiently, hidden in the brush, for hours.

Then, at approximately 9:15 AM, a Ford V8 sedan, driven by Clyde Barrow, approached. Bonnie Parker was in the passenger seat. As the car drew near, Clyde, seeing Methvin’s father seemingly stranded by the roadside, slowed down. It was the fatal error Hamer had anticipated.

What followed was a swift, brutal, and utterly decisive fusillade of gunfire. The posse, heavily armed with automatic rifles, shotguns, and pistols, opened fire without warning. There was no demand to surrender, no chance for the outlaws to react. Hamer, ever the pragmatist, knew that giving Bonnie and Clyde any opportunity to draw their own formidable arsenal would be suicidal for his team. The barrage lasted mere seconds, but over 130 rounds were pumped into the car. Bonnie and Clyde were killed instantly, their bodies riddled with bullets.

The aftermath was chaotic. News of their deaths spread like wildfire. Thousands of curious onlookers descended upon the scene, attempting to take souvenirs from the death car and even from the bodies themselves. The public, while relieved, was also morbidly fascinated by the end of the notorious duo.

Frank Hamer, true to his nature, remained understated. He had completed his mission with the same grim determination that had characterized his entire career. He later told reporters, "I hated to bust the way I did, but when it’s them or us, I didn’t hesitate."

Hamer’s career was not without its shadows. His involvement in union-busting activities during the "Dirty Thirties," particularly against striking oil workers and longshoremen, earned him criticism and cast a controversial light on some aspects of his service. He was seen by some as a tool of corporate power, standing against the working class during a period of immense economic hardship. These actions, while legal at the time, complicate his legacy and reflect the complex, often morally ambiguous role of law enforcement in a rapidly changing society.

Despite these controversies, Frank Hamer retired for good in 1949, having left an indelible mark on Texas and American law enforcement. He passed away in 1955 at the age of 71, his life a testament to a bygone era of frontier justice.

Frank Hamer was more than just the man who killed Bonnie and Clyde. He was a symbol of the transition from the untamed American West to a more structured, yet still violent, modern society. He embodied the rugged individualism and the unwavering sense of duty that defined the best, and sometimes the most controversial, lawmen of his time. His legacy is one of quiet competence, relentless pursuit, and an unwavering commitment to the law, making him a true, if sometimes complicated, American legend. His story reminds us that behind every sensational headline, there are often men and women of extraordinary grit, working in the shadows, to ensure that justice, however brutal, ultimately prevails.