Frederic Remington: The Brush, the Bronze, and the Making of the American West

In the rugged pantheon of American mythology, few figures cast a shadow as long and as iconic as Frederic Remington. More than just an artist, Remington was a chronicler, an interpreter, and ultimately, a myth-maker of the American West. His canvases and bronzes, pulsating with the raw energy of cowboys, Native Americans, soldiers, and horses, didn’t merely depict a vanishing frontier; they helped to forge the very image of the Wild West that endures in the global imagination. At a time when the vast, untamed expanses of the continent were rapidly being domesticated, Remington dedicated his life to capturing the visceral power and stark beauty of a world on the cusp of irreversible change.

Born in Canton, New York, in 1861, Remington was an Easterner by birth, a descendant of an old American family with ties to industry and publishing. His early life hardly hinted at the dusty trails and charging steeds that would define his legacy. He briefly attended the Yale School of Fine Arts, but his boisterous nature and love for sports often overshadowed his artistic studies. Yet, even then, a keen eye for observation and a natural talent for drawing were evident. The pivotal moment came in 1881, when, at the age of 19, he ventured west to Montana. This initial encounter with the vast, untamed territories ignited a lifelong obsession.

Remington wasn’t born into the saddle, nor was he a hardened frontiersman in the traditional sense. He tried his hand at ranching, mining, and even saloon-keeping in Kansas, experiencing the frontier not as a romantic observer but as a participant, albeit a somewhat green one. These experiences, however brief or challenging, provided him with invaluable insights into the daily lives, struggles, and unique character of the people and animals that inhabited this rugged landscape. He absorbed the details – the specific cut of a cowboy’s chaps, the intricate beadwork on a Native American’s moccasins, the powerful musculature of a galloping horse – details that would lend an unparalleled authenticity to his later works.

Upon returning East, Remington realized his true calling lay not in taming the land, but in capturing it on paper and canvas. He understood, with a prescient clarity, that the world he had witnessed was fading. "I knew the wild riders and the vacant land were about to vanish forever," he famously declared, "and I saw that I was in a position to preserve at least some records of it." This sense of impending loss became the driving force behind his prolific career.

His early success came as an illustrator for prominent magazines like Harper’s Weekly and Collier’s. In an era before photography became ubiquitous, Remington’s detailed and dramatic illustrations were the primary window through which millions of Americans experienced the West. He was the camera lens of his era, bringing to life tales of cavalry charges, cattle drives, and skirmishes between settlers and Native Americans. His ability to convey action, movement, and the harsh realities of frontier life quickly made him one of the most sought-after illustrators in the country. He traveled extensively throughout the West, often embedded with U.S. Army troops or living alongside cowboys and Native American tribes, meticulously sketching and documenting everything he saw. His field notebooks were filled with anatomical studies of horses, detailed drawings of saddles, firearms, and clothing, all forming an invaluable archive for his studio work.

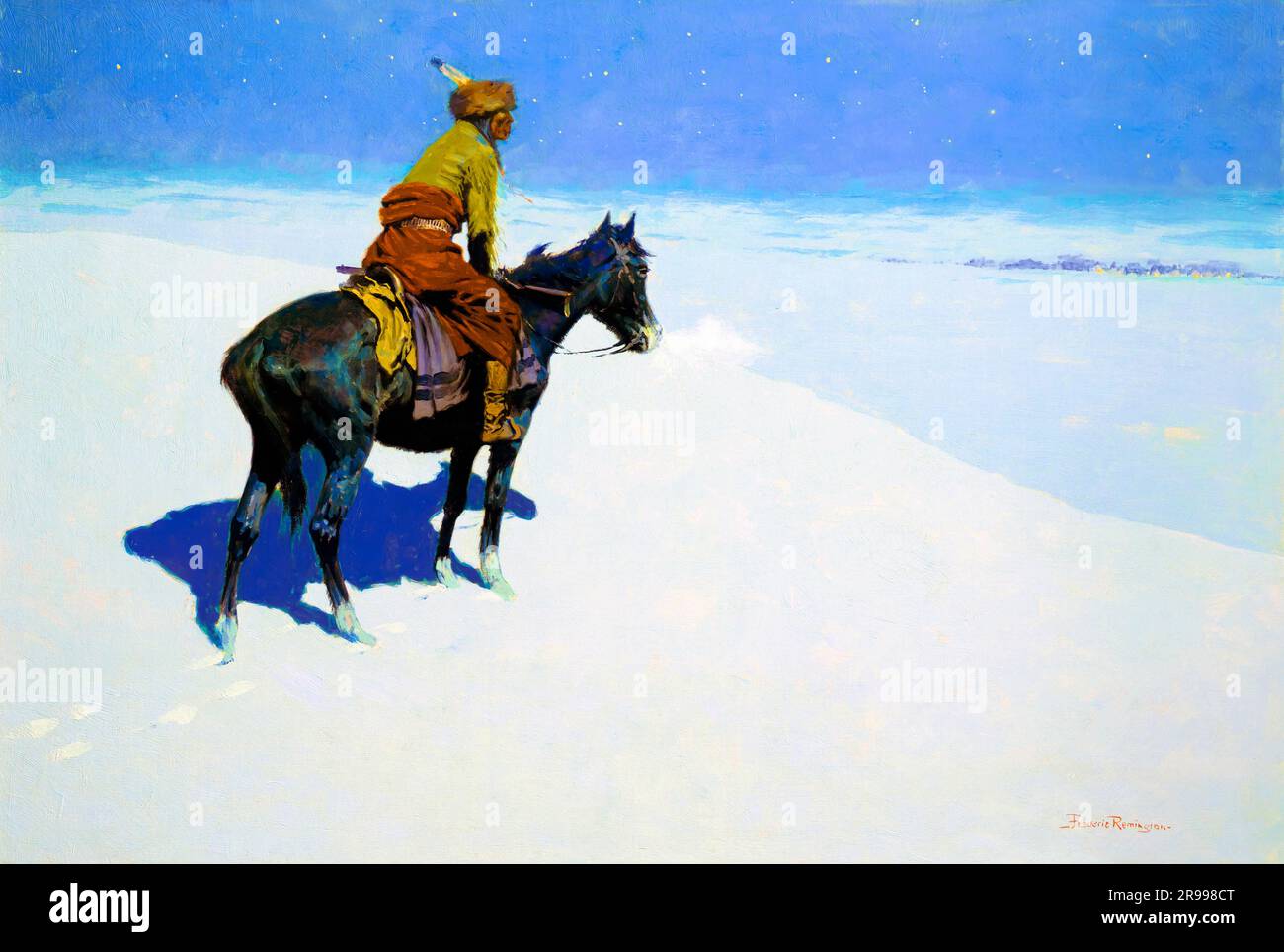

As the 1890s progressed, Remington began to transition from pure illustration to fine art painting. His canvases exploded with vibrant color and dynamic compositions. Works like Dash for the Timber (1889) and Coming to the Call (1905) showcase his mastery of depicting horses in motion, a subject he rendered with unparalleled accuracy and emotional depth. His paintings throbbed with life, capturing the dust, the sweat, and the sheer effort of men and beasts grappling with an unforgiving environment. He developed a distinctive style, characterized by strong contrasts, dramatic lighting, and a narrative focus that drew viewers directly into the heart of the action.

However, it was in sculpture that Remington achieved perhaps his most enduring and widely recognized contribution. In 1895, he cast his first bronze, The Bronco Buster. This iconic sculpture, depicting a cowboy clinging precariously to a bucking horse, perfectly encapsulated the raw energy and defiant spirit of the American West. It was an instant sensation, and its success cemented Remington’s reputation as a master of three-dimensional art. The lost-wax casting method, which he championed, allowed for intricate detail and a sense of fluid motion, bringing his figures to life with a visceral power.

The Bronco Buster was not just a commercial success; it became a symbol. Copies were gifted to presidents and foreign dignitaries, solidifying its place as an emblem of American grit and individualism. Remington followed it with other celebrated bronzes like The Rattlesnake (1905) and The Old Dragoons (1905), each demonstrating his extraordinary ability to capture tension, balance, and narrative in solid metal. His bronzes possess a tactile quality, inviting the viewer to imagine the texture of a horse’s hide, the weight of a rider, or the dust kicked up by a thundering hoof.

Remington’s vision of the West, while meticulously researched in its details, was also deeply romanticized. He often presented a heroic, almost mythical version of the cowboy and the cavalryman, engaged in a timeless struggle against a wild landscape and, at times, against equally mythologized "savages." His work undeniably played a crucial role in shaping the popular perception of the American frontier, often emphasizing themes of bravery, self-reliance, and the conquest of nature.

This romanticization, however, has also been a point of critique. Remington’s portrayal of Native Americans, while sometimes sympathetic, often conformed to prevalent stereotypes of the time, depicting them either as noble but doomed warriors or as dangerous adversaries. His art, like much of the popular culture of his era, frequently presented the West through a predominantly Anglo-American lens, often overlooking the complex realities and diverse experiences of all who inhabited it. Yet, even within these limitations, his work remains an invaluable historical record, capturing the material culture and the prevailing attitudes of a specific historical moment.

As the 20th century dawned, Remington’s style underwent a significant transformation. The boisterous, action-packed narratives of his earlier career gave way to a more introspective and atmospheric approach. He became fascinated with the subtleties of light and shadow, particularly moonlight and the eerie glow of campfires. Works like The Smoke Signal (1905) and Fired On (1907) demonstrate a shift towards a more impressionistic style, where mood and suggestion often superseded overt narrative. These later paintings, often darker in palette and more somber in tone, reflect a growing artistic maturity and perhaps a melancholic awareness that the West he had strived to preserve was truly gone. He experimented with painting nocturnes, trying to capture the elusive qualities of light under the vast Western sky, moving away from illustrative detail towards pure aesthetic effect.

A fascinating aspect of Remington’s life was his close friendship with Theodore Roosevelt. The two men, sharing a robust masculinity and a deep admiration for the "strenuous life," found common ground in their love for the West. Remington covered Roosevelt’s exploits with the Rough Riders during the Spanish-American War, creating iconic images that helped define Roosevelt’s public persona. Roosevelt, in turn, was a fervent admirer and collector of Remington’s work, recognizing its power to embody the American spirit.

Frederic Remington died unexpectedly in 1909, at the age of 48, from complications following an appendectomy. His untimely death cut short a career that was still evolving, leaving behind a vast body of work comprising thousands of illustrations, hundreds of paintings, and two dozen bronzes.

Remington’s legacy is a complex tapestry woven from historical documentation, artistic innovation, and myth-making. He was a meticulous observer who captured the material culture of the West with unmatched accuracy, providing invaluable insights for historians and ethnographers. He was an artistic pioneer who elevated the Western genre, moving it from mere illustration to the realm of fine art. And perhaps most significantly, he was a powerful storyteller whose images imprinted themselves on the American psyche, shaping how generations would visualize the cowboys, Native Americans, and soldiers who populated the frontier.

Today, Remington’s work is celebrated in museums across the United States, from the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York to the Amon Carter Museum of American Art in Fort Worth. While modern scholarship has brought a more critical eye to the historical accuracy and social implications of his romanticized narratives, the sheer artistic power and enduring appeal of his creations remain undeniable. Frederic Remington didn’t just paint the West; he etched its image into the soul of a nation, ensuring that the spirit of the American frontier, in all its rugged glory and complex reality, would gallop on forever.