From Loyal Subjects to Revolutionary Souls: The Unthinkable Journey of America’s First Patriots

The story of the American Revolution is often told as a saga of valiant rebels fighting against tyrannical oppression. While true, this narrative sometimes glosses over a profound and complex transformation: the metamorphosis of loyal English subjects, proud to be part of the British Empire, into fiercely independent American patriots, willing to shed blood for a nation that didn’t yet exist. It was a journey from fervent allegiance to radical defiance, spanning decades of evolving identity, escalating grievances, and a fundamental redefinition of liberty itself.

For over a century and a half, the inhabitants of the thirteen colonies considered themselves, first and foremost, Britons. They spoke English, read English literature, followed English laws (to varying degrees), and revered the English monarch. Many had fled England seeking religious freedom or economic opportunity, but they carried their British heritage with them across the Atlantic. They celebrated British victories, mourned British losses, and saw themselves as an integral, if distant, part of the world’s most powerful empire. This identity was reinforced by shared culture, language, and the very real protection offered by the Royal Navy.

Life in the colonies, however, fostered a unique spirit of self-reliance and local governance. Due to the sheer distance from London and the practicalities of administering a vast, growing territory, the colonies developed robust legislative assemblies. These bodies, such as Virginia’s House of Burgesses and the Massachusetts General Court, handled local affairs, raised taxes, and even controlled the salaries of royal governors. This period, often termed "salutary neglect," inadvertently allowed a strong tradition of self-governance to flourish. Colonists grew accustomed to the idea that their laws were made by representatives they elected, a principle deeply rooted in British constitutional tradition but applied with greater local autonomy than in Britain itself.

"The colonies are not independent of the mother country, but they enjoy a greater degree of freedom than any other people on earth," declared Edmund Burke, a British statesman, reflecting the prevailing view of colonial prosperity and liberty. Indeed, by the mid-18th century, the American colonies were booming, their populations exploding, and their economies thriving, largely due to their integration into the British mercantile system.

The first major crack in this Anglo-American facade appeared with the conclusion of the French and Indian War (the North American theater of the Seven Years’ War) in 1763. Britain emerged victorious, but heavily indebted. To recoup costs and assert greater control over its expanded North American territories, Parliament initiated a series of policies that would unravel the delicate balance of colonial loyalty.

The Proclamation of 1763, which restricted westward expansion beyond the Appalachian Mountains, angered land-hungry colonists. Far more incendiary, however, were the attempts to levy direct taxes. The Sugar Act of 1764, aimed at curbing smuggling and raising revenue, was a precursor, but it was the Stamp Act of 1765 that ignited the first widespread colonial outrage. This act imposed a direct tax on all printed materials – newspapers, legal documents, playing cards – requiring a special stamp.

The fury was not primarily about the amount of money involved, but the principle. Colonists argued that only their elected provincial assemblies had the right to tax them. They invoked the cherished British right of "no taxation without representation." James Otis, a Massachusetts lawyer, famously declared, "Taxation without representation is tyranny." This wasn’t a call for independence; it was a demand for their rights as Englishmen. They saw themselves as defending the very principles of British liberty against an overreaching Parliament.

The Stamp Act Congress, a gathering of delegates from nine colonies, issued a declaration asserting that "no taxes ever have been or can be constitutionally imposed on them but by their respective legislatures." Faced with widespread boycotts of British goods and fierce protests, Parliament repealed the Stamp Act in 1766, but simultaneously passed the Declaratory Act, asserting its full authority to legislate for the colonies "in all cases whatsoever." The stage was set for a fundamental clash over sovereignty.

Subsequent acts, like the Townshend Acts of 1767 (duties on glass, lead, paints, paper, and tea), continued to provoke colonial resistance. The arrival of British troops in Boston to enforce these laws led to increased tensions, culminating in the Boston Massacre in 1770, where British soldiers fired into a crowd, killing five colonists, including Crispus Attucks. This event, sensationally depicted by Paul Revere’s engraving, became a potent symbol of British tyranny.

Despite a brief lull in tensions after the repeal of most Townshend duties (except for the tax on tea), the fundamental disagreement remained. The Tea Act of 1773, designed to bail out the struggling British East India Company by granting it a monopoly on tea sales in the colonies, was perceived not as a relief, but as a cunning ploy to enforce Parliament’s right to tax. The iconic Boston Tea Party, where Sons of Liberty disguised as Native Americans dumped 342 chests of tea into Boston Harbor, was a daring act of defiance, a direct challenge to imperial authority.

Britain’s response was swift and severe. The "Intolerable Acts" (Coercive Acts) of 1774 closed Boston Harbor, curtailed Massachusetts’s self-governance, and allowed British officials accused of crimes to be tried in Britain. These punitive measures, intended to isolate Massachusetts, had the opposite effect. They galvanized the other colonies, who saw their own liberties threatened. "The cause of Boston," declared George Washington, "ever will be considered as the cause of America."

It was during this escalating crisis that the intellectual seeds of American patriotism truly began to sprout. Enlightenment thinkers like John Locke, whose ideas on natural rights – life, liberty, and property – and the social contract (government by consent of the governed) had long been read in the colonies, now took on urgent new meaning. Colonists began to articulate a philosophy that challenged the very legitimacy of Parliament’s actions. If government derived its just powers from the consent of the governed, and if Parliament was acting without that consent, then its authority was void.

In January 1776, Thomas Paine’s pamphlet Common Sense burst onto the scene, selling hundreds of thousands of copies and profoundly shifting public opinion. Paine, a recent immigrant from England, argued not for reconciliation or redress of grievances, but for complete independence. He denounced monarchy as an absurd system and British rule as a burden. "The cause of America," Paine famously wrote, "is in a great measure the cause of all mankind." He stripped away the sentimentality of loyalty to the Crown, presenting a stark, logical argument for a new, republican nation. His words resonated deeply, pushing many wavering colonists from the position of loyal subjects seeking rights to radical patriots demanding self-determination.

The shift was not universal or instantaneous. Many colonists, known as Loyalists, remained steadfastly committed to the Crown, believing that the benefits of empire outweighed the grievances, or fearing the chaos of rebellion. Families were torn apart, communities divided. But for an increasing number, the idea of being "American" – a distinct people with a distinct destiny – began to supersede their British identity.

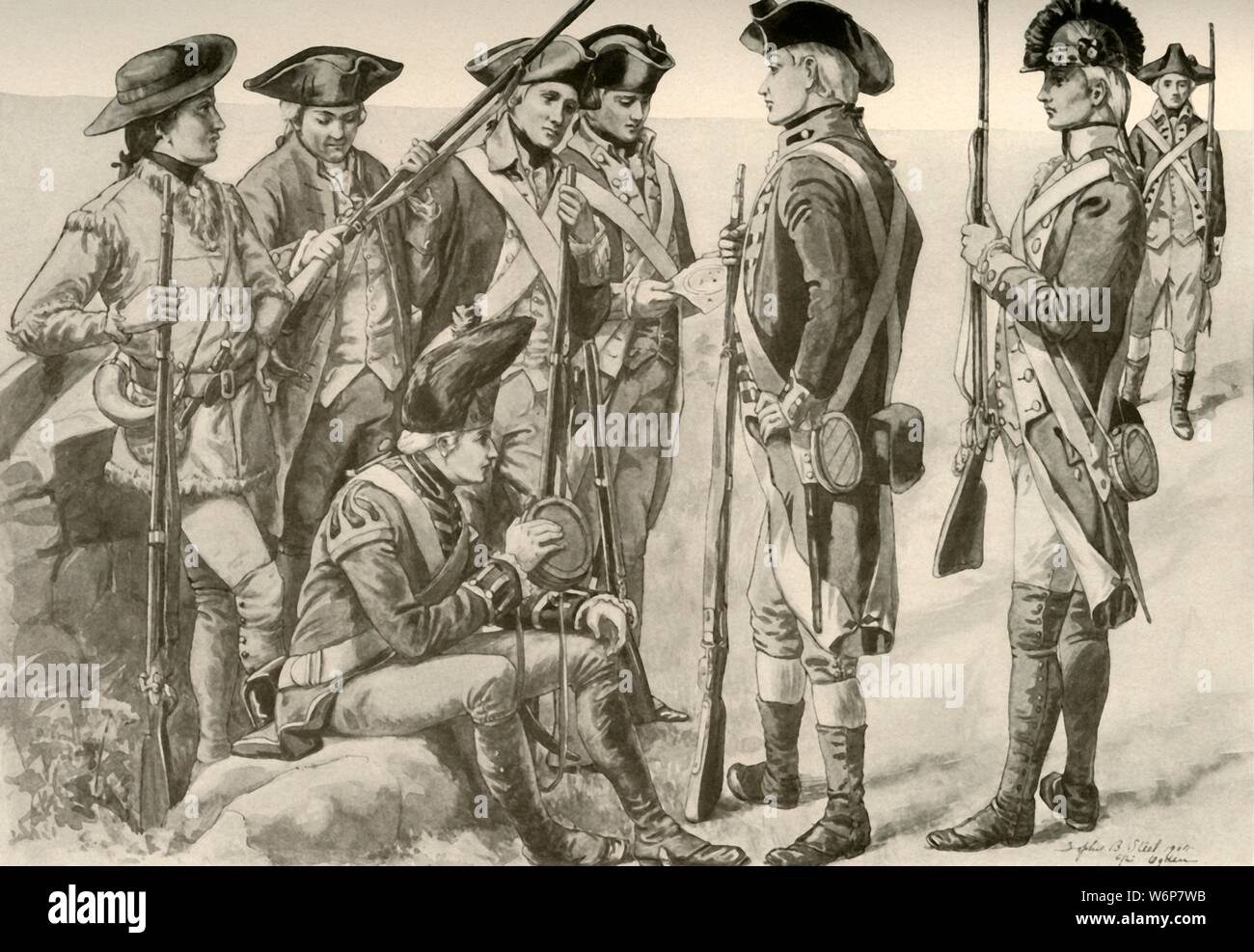

The First Continental Congress, convened in 1774, was still seeking reconciliation, drafting petitions to the King. But the "shot heard ’round the world" at Lexington and Concord in April 1775, followed by the Battle of Bunker Hill, transformed a political dispute into an armed conflict. The Second Continental Congress, meeting amidst actual warfare, slowly moved towards the inevitable. George Washington was appointed commander of the Continental Army, a truly audacious act for a group still claiming loyalty to the king.

By the summer of 1776, the momentum for independence was unstoppable. On July 2nd, the Congress voted for independence, and on July 4th, they adopted the Declaration of Independence, primarily authored by Thomas Jefferson. This document was not merely a declaration of war; it was a philosophical manifesto, articulating the core tenets of the new American identity. "We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness." These words enshrined a new national purpose, a commitment to principles that transcended mere allegiance to a monarch or an empire.

The journey from English colonial to American patriot was a complex, arduous, and often painful one. It was driven by a confluence of factors: geographical distance, the development of robust local self-governance, economic grievances, the assertion of parliamentary authority, and the potent influence of Enlightenment ideals. It was a transformation from subjects demanding their traditional rights as Englishmen to citizens asserting universal human rights, willing to fight and die for a novel concept of national sovereignty. The men and women who embarked on this unthinkable journey forged not just a new nation, but a new definition of what it meant to be free, forever changing the course of human history.