From Shackles to Strengths: The Enduring Saga of African American History in the United States

The story of African American history in the United States is not merely a subplot in the grand narrative of a nation; it is the very crucible in which American ideals of freedom, equality, and justice have been forged, tested, and often, painfully redefined. It is a saga of unimaginable suffering and extraordinary resilience, of systemic oppression met with unyielding resistance, and of a relentless pursuit of dignity against overwhelming odds. From the brutal realities of the Middle Passage to the historic election of the first Black president, this journey has shaped the soul of America in profound and irreversible ways.

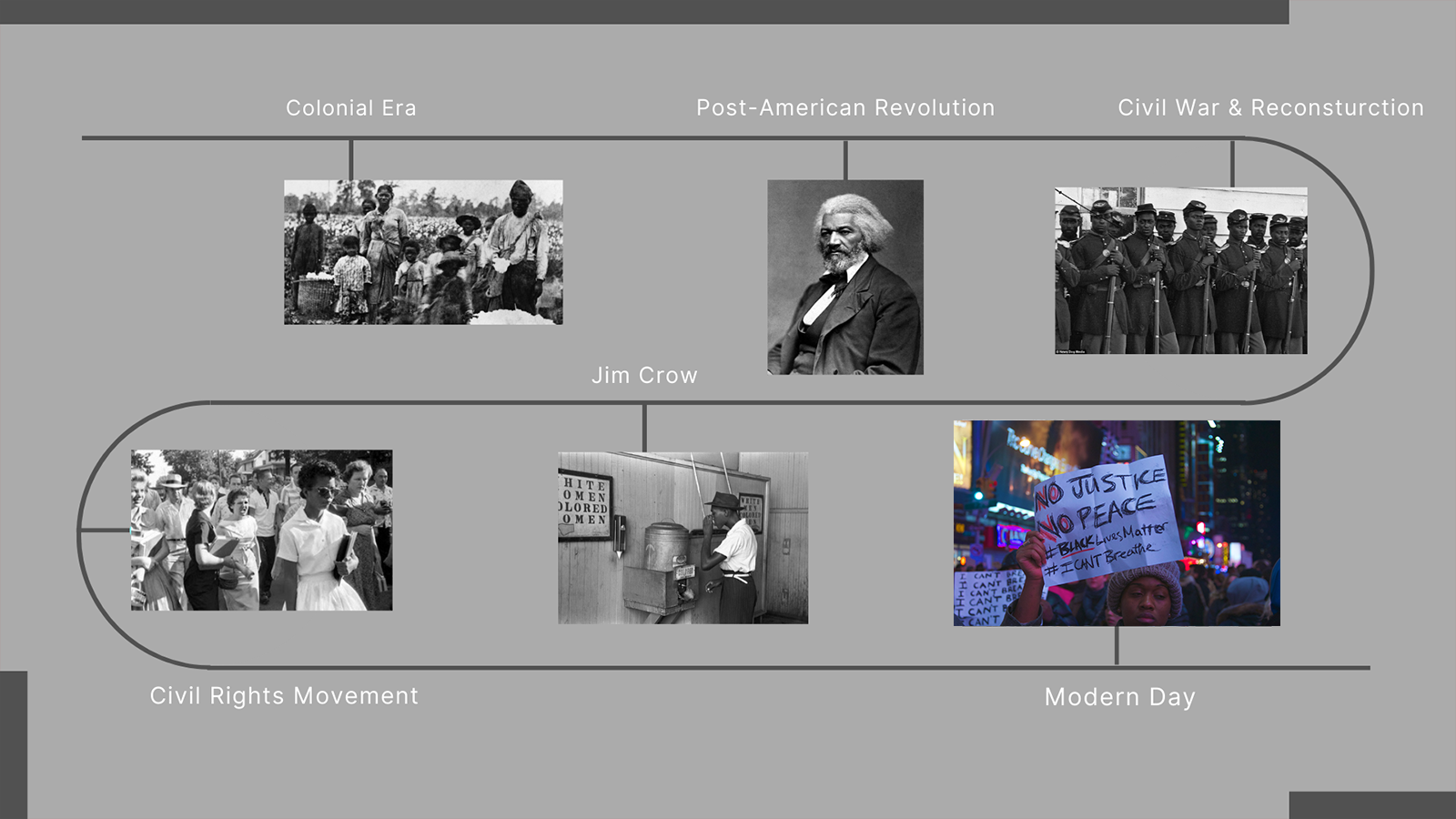

The Chains That Built a Nation: Slavery and Its Legacy (1619-1865)

The genesis of African American history in the United States is rooted in a horrifying paradox: the arrival of the first enslaved Africans in Jamestown, Virginia, in 1619, predates the Declaration of Independence by more than a century and a half. These initial twenty souls, brought against their will, marked the beginning of a brutal system of chattel slavery that would endure for over 240 years, becoming the economic engine of the nascent nation, particularly the agrarian South.

The journey itself, known as the Middle Passage, was a testament to human cruelty. Packed like cargo into the suffocating holds of slave ships, millions perished from disease, starvation, or despair. For those who survived, a life of forced labor awaited them, characterized by dehumanization, constant threat of violence, and the systematic destruction of family units. Enslaved people were considered property, not persons, their lives dictated by the whims of their masters, their bodies exploited for profit.

Yet, even in the depths of this dehumanizing system, the spirit of resistance flickered and often blazed. From subtle acts of sabotage and feigned illness to daring escapes via the Underground Railroad, led by courageous figures like Harriet Tubman – often called "Moses of her people" – enslaved Africans continuously challenged their bondage. Rebellions, though brutally suppressed, like those led by Gabriel Prosser (1800), Denmark Vesey (1822), and Nat Turner (1831), sent shivers through the white South, reminding them that the enslaved were not content with their chains. Turner’s rebellion, in particular, led to the deaths of dozens of white southerners and resulted in savage reprisals, demonstrating the high stakes of any challenge to the system.

Culturally, enslaved Africans adapted and innovated. They fused African traditions with new realities, creating unique forms of music, storytelling, and religious practices that formed the bedrock of African American culture. Spirituals, for instance, were not merely songs of solace; they often contained coded messages of escape and hope.

Emancipation’s Promise and Betrayal: Reconstruction and Jim Crow (1865-1950s)

The American Civil War, fought ostensibly to preserve the Union, ultimately led to the abolition of slavery. President Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation in 1863 declared millions of enslaved people free, a promise solidified by the 13th Amendment to the Constitution in 1865. The subsequent era of Reconstruction (1865-1877) was a brief, hopeful period where newly freed African Americans, often referred to as "freedmen," actively participated in building a new society. They voted, held public office – with over 2,000 African Americans elected to various positions, including U.S. Congress – established schools, and formed their own churches and communities.

However, this promise of a multiracial democracy was brutally short-lived. White supremacist backlash, fueled by economic anxieties and racial animosity, swiftly undermined Reconstruction’s gains. Paramilitary groups like the Ku Klux Klan emerged, employing terror, violence, and intimidation to suppress Black voting and reassert white dominance. The federal government, weary of intervention, withdrew troops from the South in 1877, effectively abandoning African Americans to the mercy of hostile state governments.

This marked the onset of the Jim Crow era, a system of legal segregation and systemic discrimination that lasted for nearly a century. Black Codes and later Jim Crow laws enforced "separate but equal" facilities for Black and white citizens, a doctrine upheld by the Supreme Court in the infamous 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson decision. In reality, "separate" was never "equal." Black schools, hospitals, public transportation, and housing were consistently inferior, underfunded, and often non-existent.

The violence of Jim Crow extended beyond legal segregation. Lynchings – public executions often carried out by white mobs with impunity – became a terrifying tool of racial control, with thousands of African Americans murdered for perceived transgressions or simply for asserting their rights. The journalist Ida B. Wells-Barnett bravely documented these atrocities, exposing the myth of Black criminality often used to justify such barbarism. The economic system, too, trapped many African Americans in sharecropping and debt peonage, effectively a new form of servitude.

The Great Migration and the Seeds of Change (Early 20th Century)

Faced with the unbearable conditions of the Jim Crow South, millions of African Americans embarked on what became known as the Great Migration. From roughly 1916 to 1970, an estimated six million Black southerners moved to northern and western cities, seeking economic opportunity, freedom from racial terror, and a chance at a better life. This demographic shift profoundly reshaped American cities, creating vibrant Black communities like Harlem in New York, Bronzeville in Chicago, and Central Avenue in Los Angeles.

These urban centers became crucibles of cultural innovation. The Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s saw an explosion of African American artistic and intellectual expression. Writers like Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston, and Claude McKay, musicians like Louis Armstrong and Duke Ellington, and thinkers like W.E.B. Du Bois articulated a new vision of Black identity, pride, and self-determination. As Du Bois famously wrote in The Souls of Black Folk (1903), "The problem of the Twentieth Century is the problem of the color-line."

Early civil rights organizations, such as the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), founded in 1909, began laying the groundwork for legal challenges to segregation. They fought against lynching, voter disenfranchisement, and discriminatory housing practices, slowly chipping away at the edifice of Jim Crow through litigation and advocacy.

The Triumphant Roar: The Civil Rights Movement (1950s-1960s)

The mid-20th century witnessed the dramatic crescendo of the Civil Rights Movement, a pivotal period that fundamentally altered the course of American history. World War II played a significant role, as African American soldiers returned home having fought for freedom abroad, only to be denied it at home, sparking a renewed determination to fight for their rights.

The landmark Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka (1954), which declared state-sponsored segregation in public schools unconstitutional, struck a powerful blow against Plessy v. Ferguson. Though resistance to desegregation was fierce – exemplified by the Little Rock Nine in 1957 – the ruling energized activists.

The movement gained unprecedented momentum with the Montgomery Bus Boycott (1955-1956), sparked by Rosa Parks’ courageous refusal to give up her seat to a white passenger. This 381-day boycott, led by the young Reverend Martin Luther King Jr., demonstrated the power of nonviolent direct action and economic pressure. King’s philosophy, deeply rooted in Christian teachings and Gandhian principles, became the moral compass of the movement. His eloquent speeches, particularly his "I Have a Dream" address at the 1963 March on Washington, galvanized the nation and the world, articulating a vision of racial harmony and equality.

The movement employed a variety of tactics: sit-ins at segregated lunch counters, Freedom Rides to challenge segregation in interstate travel, voter registration drives in the deep South, and massive marches. Organizations like the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), and the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) organized and mobilized thousands of ordinary citizens, often at great personal risk.

While King championed nonviolence, other voices emerged. Malcolm X, a charismatic leader of the Nation of Islam, articulated a message of Black nationalism and self-defense, challenging King’s integrationist approach. Though their methods differed, both men sought empowerment for African Americans and exposed the systemic nature of racism.

The movement’s persistent efforts, combined with increasing national and international pressure, finally compelled Congress to act. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 outlawed discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, or national origin, ending legal segregation in public places and employment. The Voting Rights Act of 1965 dismantled the legal barriers that had prevented African Americans from exercising their right to vote, leading to a dramatic increase in Black political participation.

Beyond the Movement: Persistent Challenges and Enduring Hope (1970s-Present)

The legislative victories of the 1960s were monumental, but they did not eradicate racism or inequality overnight. The post-Civil Rights era has been characterized by a continued struggle against systemic racism, economic disparities, and social injustice. Issues like affirmative action, urban poverty, mass incarceration, and police brutality have emerged as central concerns.

Despite the dismantling of legal segregation, de facto segregation in housing and education persists, often exacerbated by economic inequality. The wealth gap between Black and white Americans remains stark, a lingering consequence of centuries of discrimination and limited opportunities. The rise of the Black Lives Matter movement in the 21st century, sparked by the killings of unarmed Black individuals by police, underscores the ongoing fight for racial justice and accountability in law enforcement.

Yet, alongside these persistent challenges, there have been undeniable triumphs. African Americans have achieved unprecedented levels of success in every field imaginable – politics, science, arts, sports, and business. The election of Barack Obama as the first African American president in 2008 was a historic milestone, a testament to the long and arduous journey from bondage to the highest office in the land. His presidency, while not ending racial strife, symbolized a profound shift in American identity and possibility.

Today, African American history continues to unfold. It is a dynamic narrative of struggle, resilience, cultural richness, and an unwavering belief in the promise of America, even when America has failed to live up to its own ideals. The ongoing fight for true equity and justice is a testament to the enduring spirit of a people who have continuously pushed the nation to confront its past, acknowledge its present imperfections, and strive for a more perfect future. Their narrative is not just a chapter in American history; it is the bedrock upon which the nation’s truest ideals are continually tested and forged.