From Street Urchin to Syndicate Boss: The Enduring Shadow of Lucky Luciano

In the annals of American crime, few names resonate with the chilling authority and strategic brilliance of Charles "Lucky" Luciano. He was not merely a gangster; he was an architect, a visionary who transformed disparate, warring factions of the underworld into a streamlined, ruthlessly efficient corporation – the modern American Mafia. From the grimy tenements of the Lower East Side to the sun-drenched streets of Naples, Luciano’s life was a testament to ambition, violence, and an unparalleled understanding of power dynamics, leaving an indelible mark on both criminal history and the American psyche.

Born Salvatore Lucania in Lercara Friddi, Sicily, in 1897, his journey to infamy began when his family emigrated to New York City in 1906. The teeming, poverty-stricken streets of the Lower East Side became his crucible. It was here, amidst a melting pot of struggling immigrants, that young Salvatore learned the harsh realities of survival. Petty theft, street brawls, and extortion were his classroom. He quickly gravitated towards the burgeoning criminal underworld, demonstrating a precocious talent for organization and a chilling lack of sentimentality. His early associates included future titans like Meyer Lansky, a brilliant Jewish mobster who became his lifelong confidante and strategic partner, and Bugsy Siegel, the volatile enforcer. This diverse triumvirate, forged in the crucible of street crime, foreshadowed Luciano’s later, revolutionary vision for a multi-ethnic crime syndicate.

The nickname "Lucky" itself is steeped in legend. While some attribute it to his prowess at gambling, the more compelling story involves a brutal beating he endured in 1929 at the hands of rivals (possibly for refusing to work for another mob boss, or for a perceived slight). Left for dead with his throat slit and an eye gouged, he miraculously survived. The incident not only cemented his reputation for toughness but also instilled in him a deeper understanding of the futility of endless street warfare. He emerged from that ordeal with a renewed conviction: violence was a tool, not an end in itself.

The advent of Prohibition in 1920 proved to be the grand catalyst for Luciano’s ascent. The illegalization of alcohol created an unprecedented economic opportunity, transforming small-time hoodlums into wealthy entrepreneurs overnight. Luciano, alongside Lansky and other ambitious young criminals like Frank Costello and Al Capone (though Capone operated primarily out of Chicago), recognized that the old guard – the "Mustache Petes" as they derisively called the traditional Sicilian bosses – were ill-equipped to manage such a vast, complex enterprise. These old-world dons, with their rigid adherence to archaic traditions and penchant for internecine feuds, were obstacles to progress and profit.

The brewing tension between the old and new schools erupted into the Castellammarese War (1930-1931), a bloody conflict that pitted the forces of Joe Masseria against those of Salvatore Maranzano. Luciano, ever the pragmatist, initially sided with Masseria but quickly grew weary of the protracted, economically destructive war. He famously quipped, "There’s no such thing as good money or bad money. There’s just money." His focus was on business, not outdated notions of honor or vengeance. In a move that epitomized his ruthless pragmatism, Luciano orchestrated Masseria’s assassination in April 1931. Legend has it that Luciano excused himself to the restroom during a card game with Masseria, allowing Siegel, Lansky, Vito Genovese, and Joe Adonis to burst in and gun down the old boss.

With Masseria eliminated, Maranzano declared himself "Capo di tutti capi" (Boss of all Bosses). This, however, was a title Luciano could not abide. He saw it as a reversion to the very feudal structure he sought to dismantle. Just five months after Masseria’s death, Luciano arranged for Maranzano’s elimination. On September 10, 1931, Maranzano was brutally murdered in his office by a team of Jewish hitmen (reportedly to avoid an all-Italian bloodbath and make it harder for authorities to trace). This day, often referred to as the "Night of the Sicilian Vespers," marked the definitive end of the old order and the dawn of Luciano’s revolutionary vision.

In the power vacuum that followed, Luciano didn’t declare himself the sole ruler. Instead, he convened a historic meeting of crime families from across the nation. Out of this assembly, he established "The Commission," a governing body composed of the heads of the five New York families (Genovese, Gambino, Lucchese, Colombo, and Bonanno) and representatives from other major cities. The Commission was designed to be a democratic, arbitration-based system, resolving disputes without resorting to destructive gang wars. It transformed the American underworld from a chaotic collection of individual gangs into a sophisticated, nationwide syndicate, diversifying into gambling, loan sharking, labor racketeering, and legitimate businesses. Luciano, though never officially titled "Boss of Bosses," was undeniably the most influential figure on The Commission, its de facto chairman and strategic mastermind.

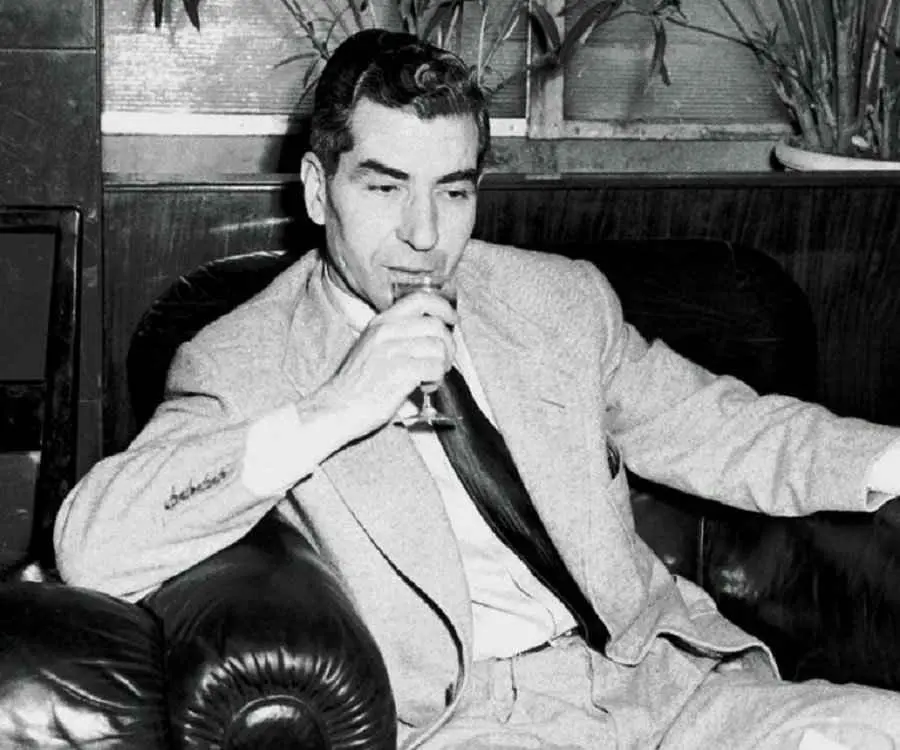

Luciano’s reign as the unseen, undisputed emperor of American organized crime was characterized by unprecedented prosperity and a blurring of lines between the underworld and legitimate society. He cultivated an image of a suave, sophisticated businessman, frequenting high-end restaurants and nightclubs, often rubbing shoulders with politicians, celebrities, and industrialists. His empire generated immense wealth, much of which was laundered through legitimate enterprises, further solidifying the Mafia’s economic footprint.

However, Luciano’s meteoric rise was not without its challenges. His lavish lifestyle and undeniable power attracted the attention of an ambitious young prosecutor named Thomas E. Dewey. Dewey, a relentless "gangbuster," made it his mission to dismantle Luciano’s empire. Unable to secure convictions for murder or other high-profile crimes, Dewey focused on a massive prostitution ring that Luciano allegedly controlled. In 1936, after a sensational trial where Luciano was famously accused of being the "pimp of pimps," he was convicted on 62 counts of compulsory prostitution and related charges. The verdict was a stunning blow to the underworld, and Luciano was sentenced to an extraordinary 30 to 50 years in Sing Sing prison.

Luciano’s incarceration marked a temporary cessation of his direct control, but his influence remained. Then came World War II, and with it, a strange twist of fate. As the United States prepared for war, concerns grew about sabotage on the New York waterfront, a vital hub for troop and supply movements. Reports of fires, suspicious sinkings, and enemy agents prompted the Office of Naval Intelligence to seek help from an unlikely source: the imprisoned Lucky Luciano. Through his associates, particularly Meyer Lansky and Frank Costello, Luciano was reportedly approached for assistance.

This clandestine agreement, known as "Operation Underworld," remains one of the most controversial chapters in Luciano’s life. The official narrative suggests that Luciano used his extensive network among longshoremen and dockworkers to ensure labor peace, prevent sabotage, and provide intelligence to the Allies, particularly regarding the Mafia’s contacts in Sicily ahead of the 1943 Allied invasion. In exchange for his cooperation, Luciano’s sentence was commuted in 1946 by New York Governor Thomas E. Dewey (the very prosecutor who put him away), on the condition that he be immediately deported to Italy.

Deported to his native Italy, Luciano settled in Naples, where he quickly re-established a degree of criminal influence. The U.S. government, however, closely monitored his activities, fearing he might attempt to re-enter the country or continue to direct the American Mafia from abroad. In 1947, he brazenly moved to Cuba, attempting to reassert direct control over his American empire. The move sparked an international incident. Under immense pressure from the U.S. government, which threatened to cut off all sugar shipments to the island, Cuba was forced to expel Luciano back to Italy.

For the remainder of his life, Luciano resided primarily in Naples, a powerful figure in the Italian underworld, albeit under constant surveillance. He lived a life of relative luxury, meeting with American mobsters who traveled to pay their respects and seek his counsel. He maintained a public facade of retirement, but intelligence agencies and law enforcement were convinced he continued to exert significant influence over drug trafficking and other international criminal enterprises.

On January 26, 1962, Charles "Lucky" Luciano, at the age of 64, collapsed and died of a heart attack at Naples International Airport. He was there to meet an American film producer about a movie based on his life. His death marked the end of an era, but not the end of his legacy. His body was eventually allowed to be returned to the United States and was buried in St. John’s Cemetery in Queens, New York, just a stone’s throw from the city where he had forged his empire.

Lucky Luciano’s impact on organized crime cannot be overstated. He was not just a powerful gangster; he was a strategic innovator who rationalized, modernized, and centralized the American underworld. He replaced chaotic, bloody feuds with a system of arbitration and profit-driven enterprise. The Commission he founded continues, in various forms, to govern organized crime in America to this day. His life story, a rags-to-riches saga twisted by criminal intent, embodies a darker side of the American Dream – an immigrant’s relentless pursuit of power and wealth, achieved through cunning, ruthlessness, and an unparalleled ability to adapt. His shadow, complex and enduring, continues to loom large over the history of crime, a chilling reminder of the man who built the mob.