Galena, South Dakota: The Quiet Echoes of a Lead-Fueled Dream

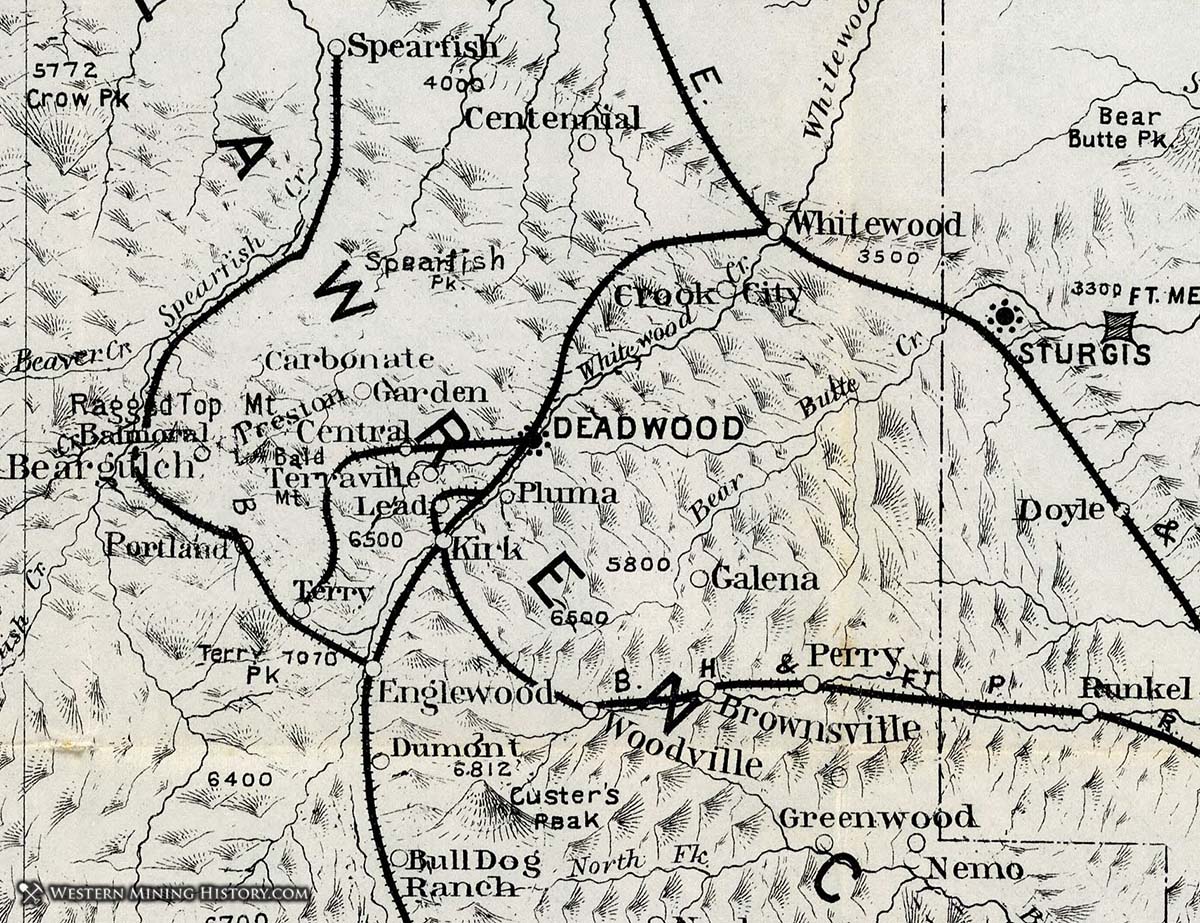

In the rugged embrace of South Dakota’s Black Hills, where the whispers of wind through ponderosa pines carry tales of gold rushes and frontier legends, lies a place that offers a different, perhaps more somber, narrative. This is Galena, a once-thriving mining town now largely claimed by nature and the relentless march of time. Unlike its boisterous neighbor, Deadwood, whose name still conjures images of Wild West outlaws and frenetic gold strikes, Galena’s story is one of lead and silver, of industrial ambition, and ultimately, of a quiet fade into the annals of history.

Today, Galena exists as little more than a scattering of weathered foundations, a few solitary, resilient structures, and a hauntingly beautiful landscape. Yet, for those who take the scenic, winding roads just north of Deadwood and Lead, Galena offers a profound glimpse into a pivotal, though often overlooked, chapter of the Black Hills’ development. It’s a testament to the ephemeral nature of boomtowns and the enduring power of a landscape that eventually reclaims its own.

The Black Hills’ Other Treasure: Lead and Silver

The initial stampede into the Black Hills in the mid-1870s was fueled almost exclusively by gold. Prospectors, defying treaties and braving the wilderness, sought the precious yellow metal in the streams and veins of the ancient mountains. But as the gold rush matured, and miners delved deeper into the earth, they began to uncover other valuable minerals. Among these was galena – lead sulfide (PbS) – a heavy, metallic-grey ore that often contained significant quantities of silver.

It was this discovery that led to Galena’s founding in 1878. While gold was certainly present in the surrounding hills, it was the rich veins of lead and silver that defined the town’s purpose. The ore was valuable not just for its lead content, but more importantly, for the silver that could be extracted from it. Silver was in high demand for coinage and industry, and its price was strong.

"Galena wasn’t chasing the flash of gold; it was built on the steady, heavy promise of lead and silver," explains local historian, Dr. Eleanor Vance, who has extensively researched the Black Hills’ lesser-known mining communities. "It represented a more industrialized phase of mining, requiring smelters and more sophisticated extraction methods than the initial placer gold operations."

The town quickly boomed. Within a few years, Galena boasted a population of several hundred, perhaps even over a thousand, at its peak. It wasn’t just miners who flocked to the area; merchants, assayers, saloon keepers, and families arrived, transforming a wilderness outpost into a bustling, if rough-hewn, community. Streets were laid out, though probably more by necessity than by design, and essential services emerged. There were general stores, blacksmiths, boarding houses, and, of course, a good number of saloons to quench the thirst and temper the hardships of the miners.

Industrial Heartbeat: The Smelters of Galena

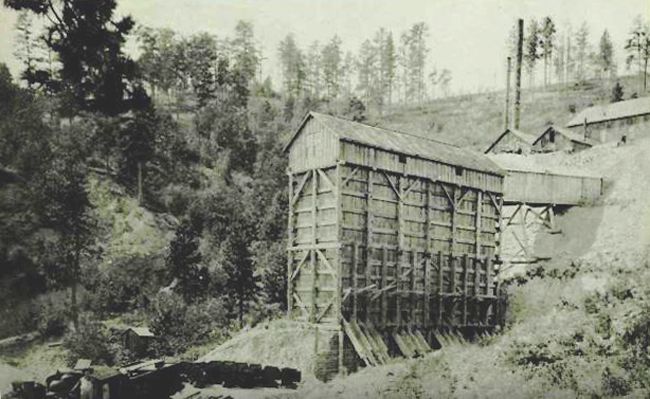

What truly set Galena apart from many other Black Hills camps was its industrial infrastructure. To process the galena ore and extract the silver, smelters were essential. The most prominent of these was the Queen Smelter, a massive operation that represented a significant investment and a technological marvel for its time and location. The Queen Smelter, along with others, became the beating heart of Galena, its towering smokestacks dominating the landscape, belching smoke that signaled industry and prosperity.

The process was arduous and dirty. Ore was crushed, then fed into furnaces where intense heat separated the lead and silver from the waste rock. This created lead "bullion," which was then shipped out for further refining. The work was dangerous, with miners toiling underground in dark, damp tunnels, facing the constant threat of cave-ins, explosions, and lung disease. Surface workers at the smelters contended with extreme heat, toxic fumes, and heavy machinery.

A glimpse into the daily life reveals a community forged in grit. "Life in Galena was hard-won," notes Vance. "Miners worked long shifts, often living in rudimentary cabins or boarding houses. Their days were defined by the rhythm of the mine and the smelter, the hope of a rich strike, and the camaraderie of shared hardship." The payrolls from the mines and smelters circulated through the town, supporting the local businesses and giving Galena a tangible economic engine. Unlike the wild, speculative nature of gold panning, lead and silver mining often involved larger companies and more structured employment, bringing a different kind of stability, albeit a temporary one.

The Inevitable Bust: When the Veins Ran Dry

Like so many boomtowns of the American West, Galena’s prosperity was intrinsically tied to the finite resources beneath its feet and the fluctuating markets of the outside world. By the late 1880s, the writing was on the wall. The richest veins of galena and silver began to play out. The cost of extracting the remaining, lower-grade ore increased significantly, making it less profitable.

Simultaneously, the price of silver began to decline on the national and international markets. The Sherman Silver Purchase Act of 1890, which mandated government purchases of silver, temporarily propped up prices, but its repeal in 1893 sent the market into a tailspin. For towns like Galena, heavily reliant on silver, this was a death knell.

The smelters, once roaring symbols of progress, fell silent. Mines closed, workers were laid off, and the population began a steady, irreversible exodus. People packed what they could and moved on, seeking opportunity in other mining districts or abandoning the hardscrabble life for agriculture or urban centers. Stores shuttered, homes were abandoned, and the once-vibrant streets grew quiet, save for the wind whistling through empty window frames.

"The decline of Galena wasn’t a sudden, dramatic collapse like some towns experienced," Dr. Vance points out. "It was more of a slow, drawn-out fade, a gradual draining of life as the economic incentives vanished. The infrastructure was too expensive to maintain without the ore, and the people followed the jobs."

Galena Today: Whispers in the Pines

Today, Galena is a ghost town in the truest sense, though a few resilient residents still call the area home, drawn by its tranquility, history, and natural beauty. The dramatic peak of its existence is long past, but its echoes persist. Driving through what was once the town center, one can discern the faint outlines of foundations where businesses once stood. Stone walls, remnants of homes or perhaps the smelter complex, peek out from beneath encroaching vegetation.

The most poignant and enduring testament to Galena’s past is often its cemetery. Here, weathered headstones stand as silent sentinels, bearing names and dates that tell tales of short, hard lives, of families uprooted, and of the ultimate price paid by those who sought their fortunes in the Black Hills. These graves are a direct, tangible link to the people who built, lived, and died in Galena, their stories etched in stone and memory.

Nature has begun its slow, inexorable reclamation. Trees grow through former buildings, and wildflowers bloom where miners once toiled. The stream that once powered mills and served as a water source now flows largely undisturbed. Yet, even in its quietude, Galena speaks volumes.

For the modern visitor, Galena offers a stark contrast to the commercial vibrancy of nearby Deadwood. There are no casinos, no reenactments, no bustling tourist shops. Instead, there is a profound sense of introspection. It invites reflection on the sheer determination of those who carved lives out of this rugged land, the cyclical nature of human endeavor, and the inevitable triumph of the natural world.

"You can almost feel the presence of the past here," says Mark Thompson, a photographer who frequently visits Galena to capture its decaying beauty. "It’s not just the ruins; it’s the stillness, the way the light filters through the trees, the sense of a grand ambition that once thrived and then simply, gracefully, receded. Galena reminds us that not all riches gleamed gold, and that even the most industrious dreams can turn to dust."

The environmental legacy of Galena’s mining operations also remains, in the form of scattered tailings piles and altered landscapes, a reminder that human ambition often leaves an indelible mark. Yet, even these scars are slowly being softened by time and the healing power of nature.

A Lasting Legacy

Galena, South Dakota, might not command the same fame as Deadwood, or the monumental awe of Mount Rushmore. But its story is no less vital to understanding the complex tapestry of the Black Hills. It represents the gritty, industrial side of the frontier, a place where the pursuit of lead and silver drove a community into existence, only to see it unravel when the veins ran dry and the markets shifted.

It stands as a silent monument to the thousands of forgotten men and women who contributed to the development of the American West, not with a pistol in hand, but with a pickaxe and a shovel, enduring hardship in pursuit of a dream. Galena is a quiet testament to the boom-and-bust cycles that defined so much of America’s expansion, a place where the echoes of a lead-fueled dream still resonate through the pine-scented air, inviting those who listen closely to remember. It is a powerful reminder that history is often found not in the grand pronouncements, but in the crumbling stones and the whispering pines of forgotten places.