Echoes in the Desert: The Enduring Story of the Goshute Tribe

By [Your Name/Journalist’s Name]

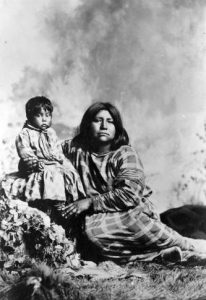

In the stark, sweeping expanses of the Great Basin, where the sky stretches endlessly and the earth offers a formidable challenge, a people have endured for millennia. They are the Goshute, a quiet and resilient tribe whose history is etched into the very landscape they call home – a narrative of profound connection, devastating loss, and an unwavering fight for survival and sovereignty. Often overlooked in the grander sagas of American history, the Goshute’s story is a powerful testament to the human spirit, echoing with the whispers of ancient traditions and the cries of modern struggles.

The Goshute, a Shoshonean-speaking people, are indigenous to what is now western Utah and eastern Nevada. Their ancestral lands, encompassing vast stretches of desert, mountains, and salt flats, might appear barren to an untrained eye. Yet, for the Goshute, this seemingly harsh environment was a bountiful larder, demanding an intricate knowledge of its rhythms and a profound respect for its delicate balance.

Masters of the Arid Land

Before the arrival of European settlers, the Goshute lived a highly nomadic existence, moving with the seasons to harvest nature’s sparse offerings. Survival was not just a skill, but an art perfected over thousands of years. Their diet was remarkably diverse, utilizing nearly every edible plant and animal available. Piñon nuts, a crucial staple, were painstakingly gathered in the autumn, providing vital protein and fat for the leaner winter months. Various roots, seeds, berries, and grasses were collected, each known for its specific properties and seasons.

Hunting was equally opportunistic and resourceful. While larger game like deer and antelope were occasionally taken, the Goshute primarily relied on smaller animals: rabbits, rodents, birds, and even insects like crickets and grasshoppers, which were harvested in abundance and dried for storage. Water, the most precious commodity, dictated their movements, with temporary camps established near springs and streams.

"Our ancestors knew this land like the back of their hand," reflects a contemporary Goshute elder, whose words encapsulate a deep-seated reverence for traditional knowledge. "They knew where every edible plant grew, where every animal burrowed, where every drop of water could be found. It was a hard life, but it was a free life, guided by the sun and the seasons."

The Goshute were organized into small, independent bands, loosely connected by kinship and shared language. There was no single overarching tribal government; instead, decisions were made communally, with leaders emerging based on wisdom, hunting prowess, or spiritual insight. This decentralized structure, while adaptive to their nomadic lifestyle, would later prove a disadvantage when confronted by the monolithic power of the encroaching American government.

The Inevitable Collision: Settlers and Gold

The mid-19th century brought an irreversible tide of change. The California Gold Rush of 1849 transformed the Great Basin into a critical thoroughfare for fortune-seekers. Wagon trains, carrying thousands of hopefuls, trampled ancient trails, consumed vital resources, and disrupted the delicate ecological balance that had sustained the Goshute for millennia. Water sources became polluted, game animals were driven away or hunted indiscriminately, and the very land that was their lifeblood was scarred by foreign passage.

Soon after, the arrival of Mormon pioneers, led by Brigham Young, brought a different kind of pressure. Intent on establishing their "Zion" in the Salt Lake Valley, they viewed the land as theirs to settle and cultivate. While Young famously advocated for "feeding the Indians rather than fighting them," this policy often translated into paternalistic attempts to "civilize" and convert the Goshute, encouraging them to adopt agriculture and abandon their traditional ways. Promises of provisions were frequently unfulfilled, leading to starvation and increasing tensions.

As more and more settlers poured into the territory, Goshute lands were steadily encroached upon. Their traditional hunting grounds were fenced off for ranching, their sacred sites disturbed, and their very existence threatened. Skirmishes inevitably broke out as the Goshute, pushed to the brink of starvation, retaliated against the theft of their resources. These isolated acts of resistance were often met with brutal reprisal by the U.S. military and settler militias, who possessed superior weaponry and numbers. Disease, too, exacted a terrible toll, with epidemics of smallpox, measles, and other foreign illnesses decimating tribal populations who had no natural immunity.

The Reservation Era: A Legacy of Poverty and Control

By the early 20th century, the Goshute, their population drastically reduced and their traditional way of life shattered, were forced onto small, fragmented reservations. The two primary Goshute communities today are the Skull Valley Band of Goshute in Utah, southwest of Salt Lake City, and the Confederated Tribes of the Goshute Reservation, located on the Utah-Nevada border near Ibapah. These reservations, often established on the least desirable lands, were a far cry from their vast ancestral territories.

Life on the reservations was characterized by poverty, dependency, and relentless pressure to assimilate. The U.S. government, through the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), imposed a foreign system of governance, discouraged traditional languages and customs, and forced Goshute children into boarding schools. There, they were stripped of their cultural identity, their hair cut, their native tongues forbidden, and their spirits often broken.

"My grandmother told me stories of the boarding school," shares a tribal member from Ibapah. "She said it was like being a prisoner. They tried to take away everything that made her Goshute. But she also said they couldn’t take away what was in her heart, what she learned from her elders before she went."

Despite these systematic attempts at cultural erasure, the Goshute held onto their identity with fierce determination. Their resilience was forged in the crucible of adversity, a quiet defiance that kept their traditions alive, often in secret.

The Nuclear Shadow: A Modern Test of Sovereignty

In recent decades, the Goshute Tribe has found itself at the center of a complex and highly controversial national debate, becoming a symbol of environmental justice and tribal sovereignty. The Skull Valley Band, facing severe economic challenges and a lack of resources, entered into an agreement with a consortium of nuclear power companies called Private Fuel Storage (PFS) in the late 1990s. The proposal was to build and operate a temporary storage facility for spent nuclear fuel on their reservation.

For the Skull Valley Goshute, the project represented a desperate bid for economic self-sufficiency, a means to break free from the cycle of federal dependency and create jobs and revenue for their small community. "We’ve been forgotten for so long," explained a tribal leader at the time, articulating the tribe’s position. "This is our chance to control our own destiny, to provide for our children."

However, the proposal ignited a firestorm of opposition from environmental groups, the State of Utah, and even other tribal nations, who raised serious concerns about safety, the potential for contamination, and the ethics of placing such a hazardous facility on a tribal reservation. Critics argued it was a prime example of "environmental racism," exploiting a vulnerable indigenous community for the nation’s nuclear waste disposal problem. The Skull Valley Goshute, a community of fewer than 150 members, found themselves embroiled in a battle that pitted their desperate need for economic development against powerful political and environmental forces.

After years of legal battles, regulatory hurdles, and shifting political landscapes, the PFS project ultimately failed to materialize. While the immediate threat receded, the controversy left an indelible mark, highlighting the profound challenges faced by small tribes striving for self-determination in the shadow of historical injustice and contemporary pressures.

Enduring Spirit and the Path Forward

Today, the Goshute continue their quiet struggle for cultural preservation and economic vitality. Efforts are underway to revitalize the Goshute language, a critical component of their identity, through educational programs and community initiatives. Tribal governments are working to diversify their economies, pursuing ventures that align with their values and respect the land.

The Goshute narrative is a powerful testament to the enduring human spirit in the face of overwhelming odds. From mastering the arid desert to surviving cultural genocide and confronting modern-day environmental challenges, they have demonstrated an extraordinary capacity for resilience. Their story serves as a vital reminder that the history of America is not just about expansion and progress, but also about the profound impact on its original inhabitants – a story that continues to unfold in the windswept silence of the Great Basin, where the echoes of the Goshute endure. Their journey is far from over; it is a continuous act of reclaiming their heritage, asserting their sovereignty, and ensuring that their unique voice continues to resonate through the generations.