Gran Quivira: Where Whispers of a Golden Dream Met Harsh Desert Reality

In the high desert plains of central New Mexico, where the wind whispers tales through the skeletal remains of stone walls, lies a place of profound history and poignant beauty: Gran Quivira. Part of the Salinas Pueblo Missions National Monument, this remote outpost is a silent testament to a collision of cultures, a testament to human resilience, and a haunting echo of a golden dream that never materialized. It is a place where the grandeur of Spanish ambition met the enduring spirit of indigenous people, only to be swallowed by the unforgiving realities of drought, disease, and conflict.

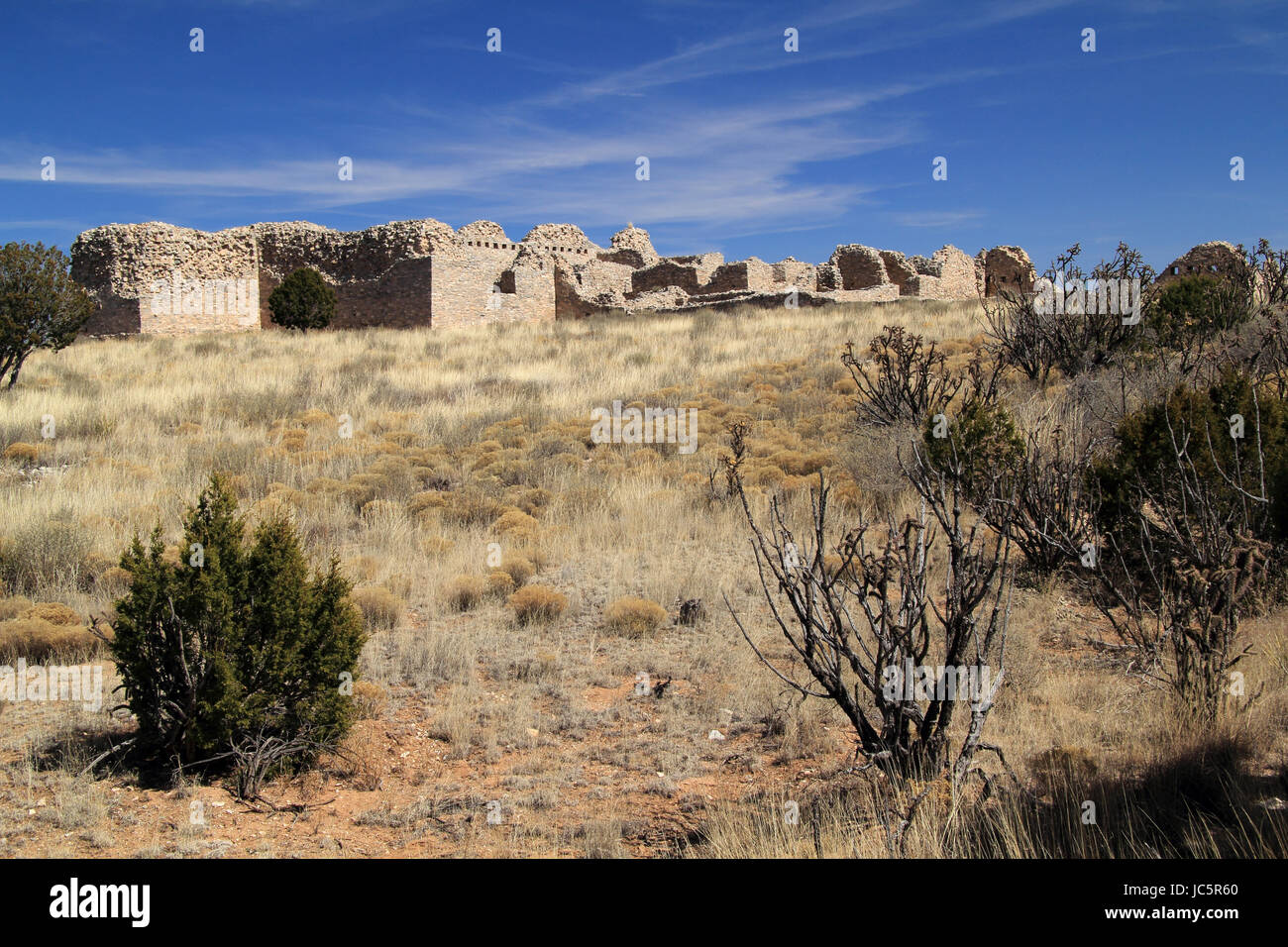

The journey to Gran Quivira is itself an exercise in quiet contemplation. Miles of undulating scrubland, dotted with juniper and piñon, give way to a dramatic mesa. As you ascend, the horizon expands, revealing an expansive sky that seems to stretch into eternity. There’s an immediate sense of isolation, a profound quiet broken only by the rustle of dry grasses and the occasional cry of a hawk. This stark setting perfectly frames the drama that unfolded here centuries ago.

The name "Gran Quivira" itself is a fascinating misnomer, a legacy of the Spanish quest for mythical riches. In 1541, Francisco Vázquez de Coronado, fueled by legends of vast wealth, led an expedition across the American Southwest in search of the fabled golden city of Quivira. His journey ultimately led him to the Great Plains of modern-day Kansas, where he found not gold, but prosperous villages of the Wichita people. Centuries later, the name, imbued with the allure of lost treasure, was mistakenly applied to this distant New Mexico pueblo. This particular "Quivira" held no gold, only the rich, poignant history of a people and their faith, a treasure far more enduring than mere metal.

Long before Spanish conquistadors dreamed of golden cities, this windswept mesa was home to the Tompiro-speaking Piro people, a sophisticated Pueblo culture that thrived on trade and dryland farming. Their ancestors had inhabited this region for centuries, building multi-story apartment-like dwellings of stone and adobe, cultivating corn, beans, and squash, and engaging in extensive trade networks that stretched across the Southwest. The site, known to its inhabitants as Las Humanas, was a bustling hub, strategically located at the crossroads of the Rio Grande Valley and the eastern plains, facilitating exchange with both other Pueblos and nomadic Plains tribes. Evidence suggests a community that was not just surviving, but flourishing, adapting to the harsh environment with ingenuity and communal effort.

The 17th century brought a new, imposing presence to the mesa: the Spanish. Following the colonization efforts of Don Juan de Oñate, Franciscan missionaries arrived with a fervent zeal to convert the indigenous population to Catholicism. They saw in the Pueblos souls to be saved and a new frontier for the Spanish empire. In the early 1600s, a small mission was established at Las Humanas, and the first modest church, San Isidro, was constructed.

The relationship between the Tompiro and the Spanish was a complex, often fraught, tapestry woven with threads of cooperation, exploitation, and resistance. While the Franciscans brought new tools, crops, and livestock, they also imposed a foreign religion and demanded labor and tribute from the Pueblo people. The Tompiro, while initially accommodating, found their traditional spiritual practices suppressed and their societal structures challenged. They were forced to build churches and mission compounds, labor in Spanish fields, and contribute resources to the distant colonial capital.

Despite these tensions, the mission at Las Humanas grew significantly. By the mid-17th century, under the guidance of friars like Fray Francisco Letrado and later Fray Diego de Santander, an ambitious new church, San Buenaventura, was begun. This was no modest chapel, but a monumental structure crafted from massive blocks of local limestone, boasting thick walls, a towering bell tower, and a spacious nave designed to impress and awe. Its sheer scale speaks volumes about the Spanish vision for the region and the immense labor extracted from the Tompiro people. Today, the majestic ruins of San Buenaventura stand as the most prominent feature of Gran Quivira, its walls still reaching skyward, a testament to both devotion and forced servitude.

"The construction of San Buenaventura was an extraordinary feat of engineering and human effort," notes a park ranger during a recent visit. "Imagine moving these enormous stones without modern equipment, all under the direction of the friars, but carried out by the hands of the Tompiro. It represents an immense investment of faith and labor, but also a significant burden on the native population."

However, the fragile balance of life at Las Humanas began to unravel with terrifying speed. The second half of the 17th century brought a series of catastrophic challenges. A prolonged, devastating drought gripped the region, turning once-productive fields into dust. Crop failures became common, leading to widespread famine. Concurrently, Apachean groups, themselves under pressure from environmental shifts and Spanish expansion, intensified their raids on the Pueblo communities, seeking food and resources. The Spanish, stretched thin and often preoccupied with their own internal conflicts, were increasingly unable to provide adequate protection to their Pueblo allies.

Compounding these woes was the silent, insidious killer: European diseases. Smallpox, measles, and influenza, against which the indigenous populations had no immunity, swept through the communities, decimating their numbers. The combined pressures of drought, famine, disease, and relentless Apache raids created an unbearable strain on the Tompiro. Their population plummeted, their resources dwindled, and their faith in the Spanish ability to protect them waned.

By the early 1670s, the once-thriving pueblo of Las Humanas, home to an estimated 3,000 people at its peak, was a ghost town. The remaining inhabitants, weakened and desperate, made the agonizing decision to abandon their ancestral homes and the monumental mission they had helped build. They migrated west, seeking refuge among other Pueblo groups along the Rio Grande. Their cultural identity, once distinct, gradually assimilated into the larger Pueblo population, and the Tompiro language eventually faded from existence.

For centuries, Gran Quivira lay largely forgotten, left to the elements and the occasional treasure hunter or cowboy. Its stone walls crumbled, its plazas became overgrown, and its story was lost to all but the most dedicated historians and archaeologists. It wasn’t until the late 19th and early 20th centuries that serious archaeological interest brought the site back into public consciousness, eventually leading to its designation as a National Monument in 1909 and its inclusion in the Salinas Pueblo Missions National Monument in 1980.

Today, the site is a powerful, silent testament to this complex history. Visitors can walk among the extensive ruins of the Tompiro pueblo, a sprawling complex of interconnected rooms and plazas, some still showing the outlines of kivas – the circular ceremonial chambers that were central to Pueblo spiritual life. The sheer size of the pueblo, estimated to contain over 300 rooms, hints at the vibrant community that once thrived here. But it is the magnificent skeleton of San Buenaventura that truly dominates the landscape, its massive stone walls reaching over 30 feet high, a stark silhouette against the vast New Mexico sky. One can still discern the outlines of the convento, the friars’ living quarters, and the large enclosed courtyard, offering a glimpse into the daily life of the mission.

To walk among these ruins is to walk through layers of time, feeling the echoes of lives lived, prayers whispered, and struggles endured. The wind, ever-present, seems to carry the murmurs of a lost language and the faint scent of piñon smoke. Gran Quivira is more than just a collection of old stones; it is a profound outdoor museum, offering invaluable insights into the pre-contact Pueblo world, the impact of Spanish colonization, and the devastating consequences of environmental change and intercultural conflict. It stands as a stark reminder of human ambition, resilience, and the fragile dance between cultures and environment. Its silent stones continue to speak volumes, urging us to listen to the whispers of the past and learn from the harsh realities that once unfolded on these beautiful, desolate plains.