Guardians of the Golden State: The Enduring Legacy of the Maidu Indians

In the heart of California, where the Sierra Nevada foothills gently descend into the vast Sacramento Valley, lies a landscape shaped by millennia of human interaction, a story told not just in geological strata but in the enduring spirit of its first peoples. Among them are the Maidu, a collective of distinct yet related Indigenous nations whose roots run deeper than the oldest redwood, whose history is intertwined with the very soil of what is now known as the Golden State. Their journey, marked by profound connection, devastating loss, and an unwavering resilience, offers a powerful testament to the strength of cultural identity against overwhelming odds.

Before the seismic shifts of European arrival, the Maidu, comprising the Mountain Maidu, Valley Maidu, Konkow, and Nisenan, thrived across a vast territory stretching from the snow-capped peaks to the meandering rivers. Their societies were complex, their economies robust, and their spiritual lives deeply interwoven with the natural world. Far from being nomadic hunter-gatherers, the Maidu practiced sophisticated land management, including controlled burns that fostered biodiversity, replenished soil nutrients, and minimized the risk of catastrophic wildfires – a practice modern environmentalists are only now fully appreciating.

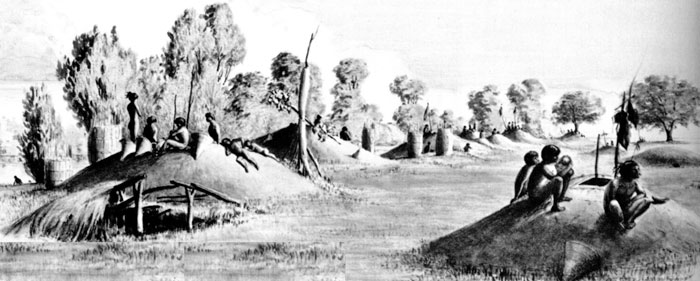

Their staple food, the acorn, was not merely gathered but meticulously harvested, processed, and stored, supporting a large and stable population. Intricate basketry, renowned for its beauty and utility, served not just as containers but as vessels of cultural knowledge, each stitch a testament to generations of skill and artistry. Their villages were permanent, their trade networks extensive, and their oral traditions rich with creation stories, practical wisdom, and historical narratives passed down through countless generations. Life was lived in harmony with the seasons, guided by a profound respect for the land and all its inhabitants.

This ancient equilibrium was shattered with the arrival of the Spanish in the late 18th century, and then utterly devastated by the American Gold Rush of 1848. The promise of instant wealth drew a human tsunami to Maidu lands, unleashing a cataclysm that few Indigenous populations worldwide have endured. Miners swarmed their rivers, desecrated their sacred sites, and violently displaced families from ancestral homes. The once pristine rivers, vital for salmon and other food sources, were choked with mining debris and poisoned by mercury.

"Our ancestors had a rich, beautiful life here," explains a Maidu elder, her voice resonating with the weight of history. "They managed this land, knew every plant, every animal. Then, almost overnight, everything changed. The newcomers saw gold, but they didn’t see us. Or if they did, they saw us as obstacles."

The impact was immediate and brutal. Diseases like smallpox and measles, to which Indigenous peoples had no immunity, swept through communities, decimating populations. Violence, often sanctioned or ignored by the nascent state government, became rampant. Massacres were common, driven by greed for land and a dehumanizing racism that depicted Native peoples as primitive obstacles to "progress." Treaties, hastily signed and rarely honored, promised land and protection but were systematically broken, pushing the Maidu onto ever-shrinking parcels or forcing them into servitude.

The numbers are stark. Prior to contact, the Maidu population numbered in the tens of thousands. Within a few decades of the Gold Rush, their numbers had plummeted by over 90%, a demographic collapse that speaks to an unparalleled tragedy. Survivors often faced forced relocation to reservations, many far from their traditional territories, where cultural practices were suppressed, languages forbidden, and children forcibly removed to boarding schools designed to "kill the Indian to save the man."

Yet, the Maidu endured. They retreated to remote mountain enclaves, practiced their ceremonies in secret, and passed down their languages and stories in hushed tones around campfires. This period of clandestine resistance was crucial for the survival of their cultural identity. Elders, through immense personal sacrifice, ensured that the threads of their heritage were not completely severed, even as the dominant society sought to erase them.

The 20th century brought new challenges and opportunities. Federal policies swung from the assimilationist agenda of the early 1900s to the devastating "Termination" era of the 1950s, which sought to dissolve tribal governments and communal landholdings. Many Maidu communities, particularly those on smaller rancherias, lost their federal recognition and the meager services that came with it, plunging them deeper into poverty and marginalization.

However, the late 20th century witnessed a powerful resurgence. Inspired by the broader Civil Rights Movement and a renewed push for Indigenous self-determination, Maidu communities began the arduous process of reclaiming their sovereignty, language, and cultural practices. This period saw the establishment of tribal governments, the development of educational programs, and a concerted effort to revitalize nearly lost traditions.

Language, the very soul of a people, became a focal point. With only a handful of fluent elders remaining, initiatives like the Maidu Language Program at the Maidu Cultural & Development Group in Chico, and similar efforts within individual tribal communities, are working tirelessly to teach the language to younger generations. "When we speak our language, we connect directly to our ancestors," a young Maidu language learner explains. "It’s more than just words; it’s a way of thinking, a way of seeing the world that is uniquely ours."

Basketry, once a daily necessity, has transformed into a powerful symbol of cultural resilience and artistic expression. Maidu weavers, often learning from elders who painstakingly preserved the craft, create pieces that are not just beautiful but embody the spirit of their ancestors. These baskets are more than art; they are prayers, stories, and a tangible link to a heritage that refused to die. Ceremonies, once held in secret, are now performed more openly, bringing communities together to celebrate their traditions, heal historical trauma, and reaffirm their connection to the land.

Economically, many Maidu tribes, like others across Indian Country, have leveraged tribal gaming as a means to achieve self-sufficiency. Revenues from casinos, such as the Gold Country Casino Resort operated by the Enterprise Rancheria Maidu, provide essential funding for tribal services – healthcare, housing, education, elder care, and cultural preservation – that were historically denied or woefully inadequate. While gaming can be a complex issue, for many tribes, it has been a vital tool for rebuilding their nations and investing in their people’s future.

Beyond economic development, the Maidu are increasingly at the forefront of environmental stewardship. Their traditional ecological knowledge, passed down through generations, offers invaluable insights into sustainable land management. Maidu fire practitioners, for example, are working with state and federal agencies to reintroduce cultural burning practices that reduce wildfire risks and promote healthy ecosystems – a stark contrast to the destructive policies of the past. They advocate for clean water, healthy forests, and the protection of sacred sites, seeing themselves as guardians of the land, not just its inhabitants.

"We have always been stewards of this land," affirms a Maidu tribal leader. "Our practices ensured its health for thousands of years. Now, we are reclaiming that role, not just for our people, but for everyone who lives here. The land remembers, and we remember what it taught us."

Despite these successes, challenges remain. The long shadow of historical trauma – the intergenerational effects of genocide, forced assimilation, and poverty – continues to impact Maidu communities, manifesting in health disparities, lower educational attainment, and social issues. The fight for full federal recognition for some unacknowledged groups continues, as does the struggle to reclaim ancestral lands and protect sacred sites from development.

Yet, the spirit of the Maidu remains unbroken. Their story is not one of victimhood, but of survival, adaptation, and profound cultural strength. From the ancient villages to the modern tribal offices, from the quiet weaving of a basket to the vibrant rhythm of a ceremonial dance, the Maidu are a living testament to the enduring power of identity. They are not relics of the past but vibrant, dynamic nations actively shaping their future, contributing their unique wisdom and resilience to the tapestry of California and beyond. Their voices, once suppressed, now echo through the valleys and mountains, a powerful reminder that the first guardians of the Golden State are still here, their legacy etched forever in the land they call home.