The Living Line: Haida Carving as a Language of Spirit and Survival

HAIDA GWAI, BC – More than mere ornamentation, the traditional carving styles of the Haida Nation of Haida Gwaii (formerly the Queen Charlotte Islands) represent a profound and intricate visual language. Forged over millennia in red cedar, argillite, and the very spirit of the Pacific Northwest, these carvings are not just art objects; they are living testaments to history, cosmology, lineage, and an enduring cultural resilience that has defied the profound pressures of colonialism. To understand Haida carving is to delve into a worldview where the human, animal, and spiritual realms are inextricably linked, and where every line, curve, and ovoid tells a story centuries in the making.

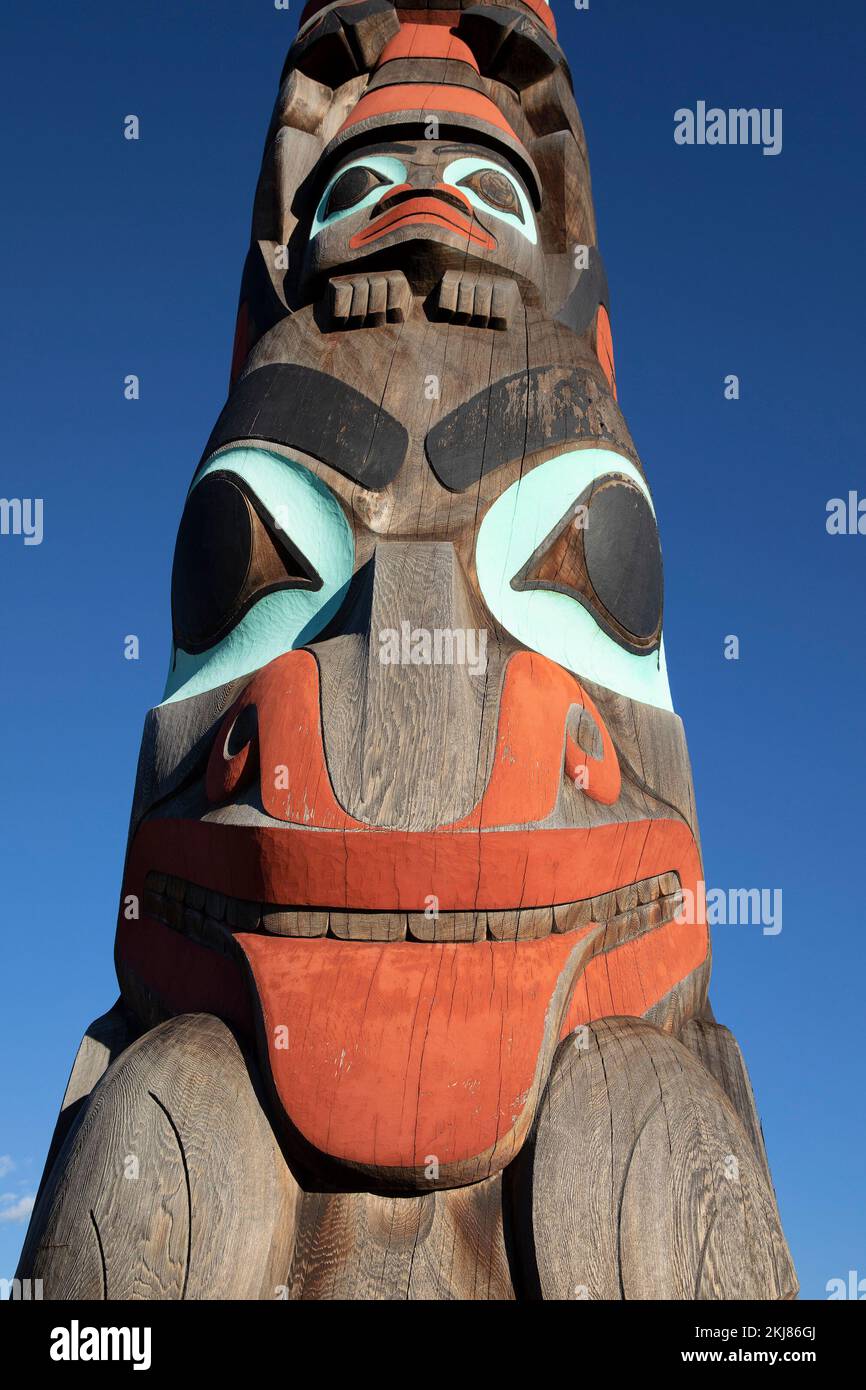

At its heart, Haida art is defined by "Formline," a sophisticated visual grammar that dictates the flow and structure of every composition. This is not a casual artistic style but a rigorous system of interconnected shapes, primarily ovoids (squashed circles), U-forms (U-shaped elements), and S-forms (S-shaped elements), all interconnected by continuous, swelling, and tapering lines. These primary lines, typically black, define the main anatomical features of figures, while secondary and tertiary lines, often red or blue-green, add detail, texture, and a dynamic sense of movement.

"It’s a language, you know," explained the late Bill Reid, one of the most celebrated Haida artists of the 20th century, whose work was instrumental in the revitalization of Haida art. "It’s a way of expressing the history of the people, the mythology of the people, the whole way of life." Reid’s words underscore the functional nature of this art; it was never simply "art for art’s sake." Instead, it served as a visual record, a mnemonic device for oral traditions, and a powerful symbol of clan identity and prestige.

The Ancestral Brushstroke: Deep Roots and Sacred Materials

The roots of Haida carving stretch back thousands of years, long before European contact. Archaeological evidence suggests that the fundamental principles of Formline were established and refined over millennia, reflecting a sophisticated society deeply attuned to its environment. The primary medium for monumental works was and remains the Western Red Cedar (Thuja plicata), a tree revered by the Haida as a sacred relative. Its soft, straight grain, natural resistance to rot, and vast size made it ideal for everything from towering totem poles to massive ocean-going canoes, longhouses, and intricate masks.

Carvers would select trees with reverence, often singing to them before felling. Tools were traditionally made from stone, bone, shell, and beaver teeth, gradually replaced by iron and steel tools acquired through trade. The adze, a distinctive tool with a blade at right angles to the handle, was crucial for shaping the rough form of a carving, its rhythmic chipping leaving a characteristic faceted surface. Fine detail work was achieved with knives and chisels.

Beyond cedar, the Haida are unique for their mastery of argillite, a soft, black carbonaceous shale found only on Haida Gwaii, specifically from a quarry on Slatechuck Mountain. This material, resembling coal but softer, allows for incredible detail and takes a high polish. While its use pre-dates European contact, argillite carving flourished in the post-contact era, as it was easily transportable and appealing to traders and collectors. These intricate sculptures, often depicting mythological creatures, human figures, or miniature totem poles, became an important source of income for Haida families during periods of economic hardship.

Iconography and Storytelling: A Pantheon of Power

The figures depicted in Haida carving are drawn from a rich tapestry of mythology and the natural world, each carrying layers of meaning. Common crest figures include:

- Raven: The trickster, creator, and culture hero. Often depicted with a long, straight beak, large eyes, and a prominent forehead. The Raven is central to many origin stories, responsible for bringing light, fresh water, and salmon to the world.

- Eagle: A symbol of peace, friendship, and power. Distinguished by its strong, curved beak, often with a downward curve. Eagle clans and Raven clans form the two main moieties (kinship divisions) of Haida society, intermarrying to maintain balance.

- Bear: Represents strength, wisdom, and a close connection to the land. Characterized by a broad snout, large teeth, and claws.

- Killer Whale (Orca): A powerful crest, representing strength, dignity, and a connection to the sea. Often depicted with a large dorsal fin, blowhole, and distinctively shaped tail flukes.

- Beaver: Known for its industriousness, creativity, and building skills. Recognizable by its two large incisors, a cross-hatched tail, and often holding a stick.

- Frog: A symbol of good luck, wealth, and the ability to move between worlds (land and water). Often depicted with a wide mouth and large eyes.

These figures are rarely static. Haida art excels at depicting transformation, where one creature subtly merges into another, or where parts of a human or animal body take on the characteristics of another being. This reflects the Haida belief in the fluidity of boundaries between species and the spirit world, and the ability of shamans to transform.

A Culture Under Siege: The Dark Period

The arrival of European traders and settlers in the late 18th and 19th centuries brought profound changes, many of them devastating. Diseases like smallpox decimated the Haida population, reducing it by an estimated 90% by the early 20th century. More insidious was the Canadian government’s active suppression of Indigenous cultures, particularly through the Potlatch Ban (1884-1951), which outlawed traditional ceremonial gatherings where wealth was distributed, status affirmed, and art displayed.

This ban, coupled with the establishment of residential schools that stripped children of their language and cultural identity, pushed Haida art to the brink of extinction. Without the potlatch, the primary social and economic driver for monumental carving vanished. Many totem poles were left to decay or were confiscated and sold to museums, often without the consent of their rightful owners. For several generations, the intricate knowledge of Formline and the complex protocols of carving were largely lost, surviving only in fragmented memories and the scattered collections of museums worldwide.

The Spark of Revival: Bill Reid and Robert Davidson

Despite the cultural genocide, the Haida spirit of creation endured. The mid-20th century saw the beginnings of a remarkable cultural renaissance, largely spearheaded by a few visionary artists. Bill Reid (1920-1998), a Haida descendant who initially pursued a career in broadcasting, rediscovered his heritage through studying museum collections of Haida art. He meticulously analyzed the works of ancestral masters like Charles Edenshaw, learning the grammar of Formline and applying it to his own innovative creations in gold, silver, argillite, and monumental cedar. Reid’s work, such as "The Raven and the First Men" (at the Museum of Anthropology in Vancouver) and "Spirit of Haida Gwaii" (at the Canadian Embassy in Washington, D.C., and Vancouver Airport), brought Haida art to international prominence and inspired a new generation.

Another pivotal figure was Robert Davidson (b. 1946), a direct descendant of Charles Edenshaw. In 1969, at the age of 22, Davidson carved and raised the first totem pole in Old Massett, Haida Gwaii, in nearly a century. This event, witnessed by elders who remembered the old ways, was a powerful symbolic act of cultural reclamation. Davidson dedicated himself to not just mastering the traditional forms but also to teaching and mentoring, ensuring that the knowledge would be passed on. His commitment to precision, innovation, and community engagement has made him a beacon for contemporary Haida art.

Carving a New Path: The Living Legacy

Today, Haida carving is flourishing. A new generation of artists, building on the foundations laid by Reid and Davidson, is not only preserving traditional techniques but also pushing the boundaries of the art form. They are carving new totem poles for their communities, creating stunning jewelry, designing contemporary clothing and textiles, and experimenting with new mediums while always adhering to the fundamental principles of Formline.

The art is also playing a crucial role in the ongoing process of reconciliation and cultural healing. Totem poles repatriated from museums are being welcomed home with emotional ceremonies, symbolizing the return of ancestral spirits and knowledge. The act of carving itself is a powerful connection to the past, a meditation on identity, and a profound act of self-determination.

In a world increasingly homogenized, the unique and dynamic carving styles of the Haida Nation stand as a testament to the enduring power of culture. Each fluid line, each intricate ovoid, is a whisper from the ancestors, a vibrant narrative of a people deeply connected to their land, their history, and their spirit. Haida carving is not a relic of the past; it is a living, breathing language, continually evolving, and eloquently speaking of survival, beauty, and the profound wisdom embedded in the very heart of Haida Gwaii.