The Rhythmic Pulse of Time: Unveiling the Hopi Ceremonial Calendar

By [Your Name/Journalist Alias]

High atop the ancient mesas of northeastern Arizona, where the vast sky meets the ochre earth, the Hopi people have maintained a profound connection to their ancestral lands and traditions for millennia. Unlike the linear progression of Western time, the Hopi experience of existence is cyclical, deeply interwoven with the rhythms of nature, the movements of the sun and stars, and the sacred duties passed down through generations. At the heart of this enduring culture lies the Hopi ceremonial calendar – not merely a schedule of events, but the very heartbeat of their spiritual, social, and agricultural life.

To understand the Hopi ceremonial calendar is to grasp the essence of their worldview: a continuous endeavor to maintain balance, ensure fertility, and pray for rain in an arid land. It is a testament to resilience, a living narrative of their emergence into the Fourth World, and a sacred contract with the spiritual forces that govern their existence.

The Foundation: Cosmology and Community

The Hopi believe they emerged from an underworld, guided by their spiritual leaders, to their present home on the mesa tops. Their mission, as given by the Creator, is to be the caretakers of this land, living in harmony with all creation and performing the necessary ceremonies to maintain cosmic balance. This responsibility is known as Hopiit, meaning "people of peace" or "those who live by the Hopi way."

Every ceremony, every song, every prayer, is a deliberate act in this ongoing stewardship. The calendar is not a static list but a dynamic flow, dictated by the seasons, the agricultural cycle—especially the cultivation of corn, their sacred staple—and the phases of the moon. Each clan and religious society holds specific responsibilities for different ceremonies, ensuring that the collective spiritual work of the community is continuously performed.

The kiva, a subterranean ceremonial chamber, is the sacred epicenter of much Hopi spiritual life. Here, men gather in secret for days or weeks, preparing for public dances, crafting ceremonial objects, and performing rituals crucial to the success of the upcoming events. These preparations are as vital as the public display, embodying the deep commitment and intense spiritual focus of the participants.

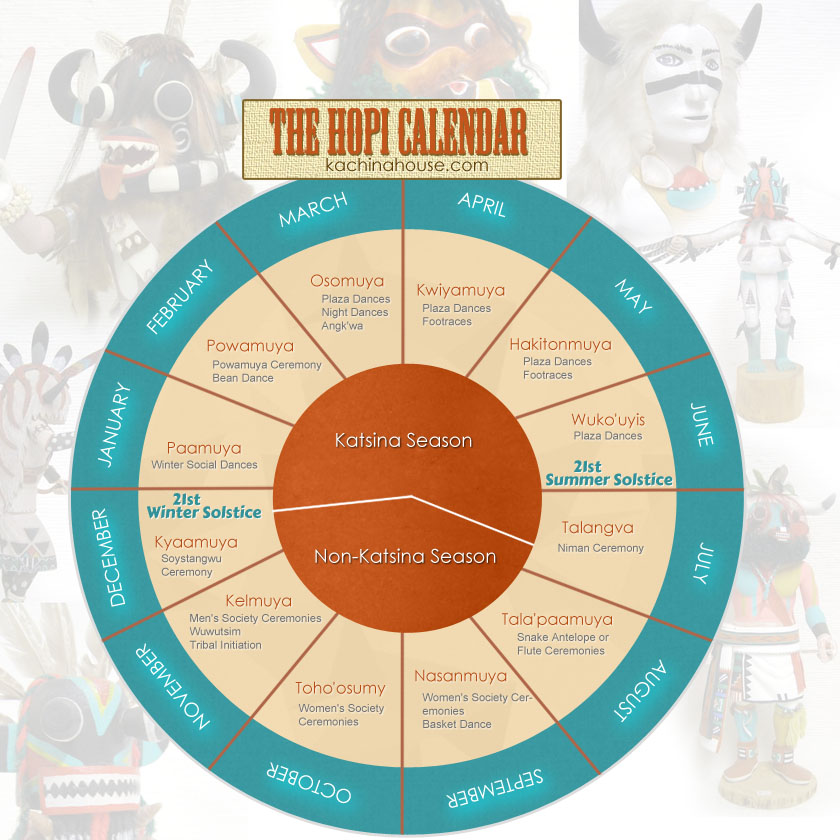

The Annual Cycle: A Journey Through Sacred Time

The Hopi ceremonial year generally begins and ends with the winter solstice, a period of introspection and renewal. While many ceremonies are private and closed to outsiders, certain public dances, particularly those involving the Katsinam, offer glimpses into this profound spiritual world.

1. Soyal (Winter Solstice – December/January): The Turning of the Year

The ceremonial year begins with Soyal, held around the winter solstice. This is a crucial time for the Hopi, marking the shortest day of the year and the symbolic "return" of the sun. It is a period of intense prayer and ritual to ensure the sun’s strength for the coming growing season. Clan leaders and religious society members engage in kiva ceremonies, offering prayers for the well-being of the village, the fertility of the land, and abundant snow and rain. Effigies are made, seeds are blessed, and the plans for the coming year are laid out. It is a time for renewing commitment to the Hopi way of life.

- Interesting Fact: During Soyal, prayer feathers (nönöngata) are created and placed in fields and homes, carrying the prayers for health, growth, and prosperity.

2. Wuwuchim (November – Pre-Soyal): Initiation and Purification

Preceding Soyal, in November, is the Wuwuchim ceremony. This is a significant men’s initiation ceremony, inducting young men into the sacred societies. It is a period of purification, spiritual education, and the passing on of ancient knowledge. Fire plays a central role in Wuwuchim rituals, symbolizing cleansing and renewal. It marks a transition from boyhood to responsible manhood within the Hopi spiritual framework.

3. Powamuya (Bean Dance – February/March): Purification and Katsina Emergence

As winter begins to wane, Powamuya, or the Bean Dance, marks a pivotal transition. It is a ceremony of purification and preparation for the spring planting season. During this time, bean sprouts are grown in the warmth of the kivas, symbolizing the hope for a bountiful harvest. This is also when the Katsinam (plural of Katsina) formally emerge from their spiritual home in the San Francisco Peaks and begin their public dances. Katsinam are spiritual beings, messengers from the spirit world, who embody the forces of nature, ancestors, and various aspects of the Hopi cosmos. They bring blessings, rain, and provide moral instruction to the community, especially the children.

4. Katsina Dances (Spring/Early Summer – March-July): Public Blessings and Education

Throughout the spring and early summer, various Katsina dances are held in the village plazas. These vibrant public spectacles are a feast for the senses, with the rhythmic beat of drums, the rattle of turtle shells on dancers’ legs, and the sight of intricately costumed Katsinam moving in unison. Each Katsina has a specific purpose and meaning, and their appearances are vital for community well-being. These dances are not mere performances; they are sacred rituals performed to bring rain, ensure the fertility of the crops, and reinforce communal values. Children receive Katsina dolls, which are not toys but educational tools to learn about the different Katsinam and their roles.

- Quote: As Hopi scholar Lomawaima (a common Hopi name) often explained, "The Katsinam are not simply dancers; they are the living presence of the spirits, bringing their power and blessings directly to the people."

5. Niman (Home Dance – July): Farewell to the Katsinam

The Niman, or Home Dance, typically held in July, marks the culmination of the Katsina season. This ceremony is a poignant farewell to the Katsinam as they return to their spiritual home. It is a deeply spiritual event, signifying the end of the public Katsina appearances until the following year. The Niman dance is often characterized by the Eototo and Aholi Katsinam, who represent the essential elements of rain and spiritual power. It is a time for final blessings, reflection on the lessons learned, and preparation for the intense agricultural work of harvest.

6. Snake/Antelope Dance (Biennial – August): Deepest Prayers for Rain and World Balance

Perhaps the most globally recognized, and often misunderstood, Hopi ceremony is the Snake Dance, which typically occurs biennially in August, alternating with the Flute Dance. This is an intensely sacred and private ceremony, with only a small portion visible to outsiders. For days, members of the Snake and Antelope societies engage in kiva rituals, handling live snakes, including rattlesnakes, which are seen as brothers and messengers to the underworld. The public portion involves the dancers carrying the snakes in their mouths, releasing them at the four cardinal directions to carry prayers for rain and fertility back to the earth.

- Interesting Fact: The Snake Dance is not about "snake charming" or fear. It is a profound act of humility and prayer, where the snakes are revered as sacred beings capable of carrying the Hopi people’s desperate pleas for rain and the world’s balance directly to the spirit world. Misinterpretations often arise from a lack of understanding of its deep spiritual context.

7. Flute Dance (Biennial – August): Water and Fertility

In the years the Snake Dance is not performed, the Flute Dance takes its place in August. This ceremony is equally significant, focusing on water and fertility. Performed by the Blue Flute and Gray Flute societies, it involves processions to sacred springs and the performance of ancient songs and rituals to encourage abundant rainfall and ensure the health of the springs and waterways vital to the arid Hopi homeland.

8. Butterfly Dance (September): Harvest and Youth

Following the main summer ceremonies, the Butterfly Dance is typically held in September. This is a more social and less strictly ceremonial dance, often performed by young men and women. It is a thanksgiving for the harvest, a celebration of life, and a joyful expression of community. The colorful costumes, intricate footwork, and graceful movements evoke the beauty of butterflies and the bounty of the season. It is often a time for courtship and community bonding after the rigorous summer ceremonies.

9. Harvest Dances (Various – October): Gratitude and Sustenance

As autumn progresses, various harvest dances may be held depending on the specific village and its traditions. These are generally communal celebrations of the successful harvest, expressing gratitude for the corn, beans, and squash that sustain the community through the winter months. They reinforce the deep connection between the Hopi people, their land, and the spiritual forces that provide for them.

The Keepers of Tradition: Resilience in a Changing World

The meticulous performance of this ceremonial calendar relies on a complex system of clan leadership, priestly societies, and the rigorous training of initiates. Knowledge is passed down orally, generation to generation, through stories, songs, and direct participation. Elders carry immense wisdom, serving as living libraries of their people’s history and spiritual obligations.

In an increasingly globalized world, the Hopi face immense challenges in preserving their traditions. Modern education, economic pressures, the lure of urban centers, and the encroaching influences of the outside world constantly test the fabric of their ancient way of life. Climate change, bringing more unpredictable weather patterns, also directly impacts their rain-dependent agricultural practices and thus their ceremonial cycle.

Yet, the Hopi remain fiercely committed to their heritage. The ceremonies continue, often with great sacrifice on the part of the participants, who balance traditional duties with the demands of contemporary life. This unwavering dedication is a testament to the profound belief in their spiritual path and the understanding that their existence, and indeed the balance of the world, depends on the continuity of these sacred rites.

Conclusion: A Living Legacy

The Hopi ceremonial calendar is far more than a schedule; it is a profound articulation of their identity, their covenant with the land, and their enduring spiritual mission. It is a living, breathing testament to a culture that views time not as a line to be conquered but as a sacred cycle to be honored. For the Hopi, the past, present, and future are intertwined in a continuous dance of prayer, responsibility, and renewal.

In a world increasingly disconnected from natural rhythms, the Hopi offer a powerful reminder of the deep human need for spiritual connection, community, and stewardship of the earth. Their ceremonies, veiled in sacred privacy, continue to beat the rhythmic pulse of time, ensuring the vitality of their culture and, in their belief, contributing to the balance and well-being of the entire world. To witness even a fragment of this living legacy is to glimpse a timeless wisdom that resonates far beyond the mesas of Arizona.