Guardians of the Desert Harvest: The Enduring Wisdom of Hopi Traditional Farming

By [Your Name/Journalist’s Name]

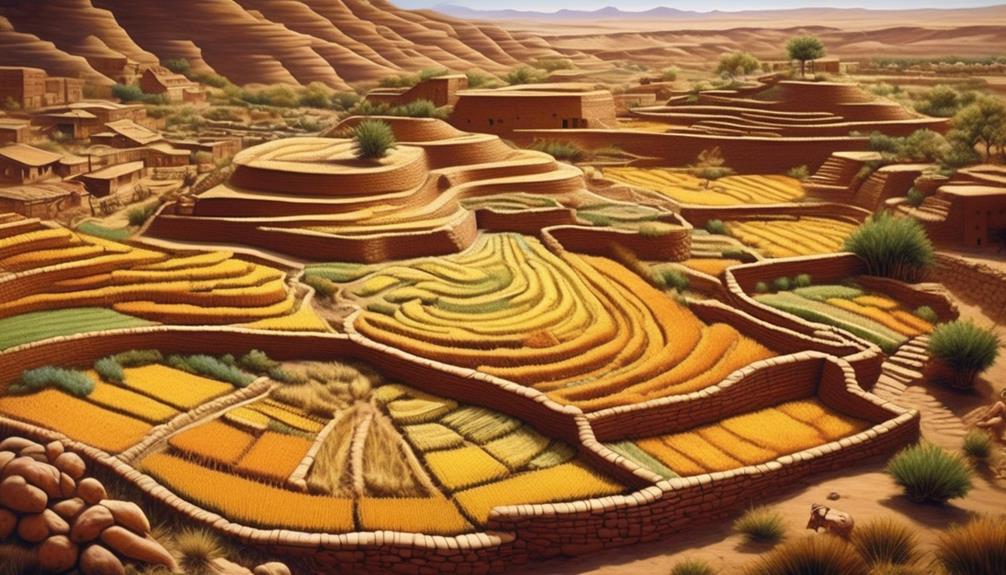

On the high, arid mesas of northeastern Arizona, where the wind whispers ancient tales across the sun-baked earth, a remarkable testament to human ingenuity and spiritual resilience unfolds. For over a thousand years, the Hopi people have cultivated a profound relationship with this unforgiving landscape, coaxing life from land that seems to offer little. Their traditional farming practices are not merely agricultural techniques; they are a living philosophy, a sacred covenant, and a profound lesson in sustainability that resonates far beyond the boundaries of their sovereign nation.

In a world increasingly grappling with food security, climate change, and the ecological footprint of industrial agriculture, the Hopi way of farming stands as a powerful counter-narrative. It is a system born of deep observation, intergenerational knowledge, and an unwavering belief in the interconnectedness of all life.

The Desert’s Embrace: A Challenging Canvas

The Hopi reservation, nestled within the vast expanse of the Four Corners region, receives an average of just 10 inches of rain annually. Summers are scorching, winters bring harsh winds, and the soil is often sandy and thin. By conventional agricultural standards, it is an impossible place to farm. Yet, here, fields of vibrant blue corn, beans, and squash thrive, nourished by practices honed over centuries.

"Our ancestors didn’t just survive here; they flourished," says Lomayesva, a Hopi elder and farmer, his eyes crinkling at the corners as he gestures towards a distant cornfield. "They understood this land, not as something to conquer, but as something to cooperate with. Every plant, every drop of water, every stone has a spirit, and we are part of that spirit."

This deep spiritual connection is the bedrock of Hopi farming. Corn, particularly the revered blue corn, is not just a crop; it is the physical and spiritual heart of the Hopi people, embodied in their ceremonies, their creation stories, and their daily sustenance. The corn plant, Hopi katsina, is seen as a sacred being, representing life, nourishment, and the continuous cycle of existence. Planting is a prayer, cultivation is an act of devotion, and harvest is a celebration of gratitude.

Ingenious Techniques: Cultivating Resilience

The Hopi’s mastery of dryland farming is unparalleled. Their techniques are a sophisticated blend of passive water harvesting, soil preservation, and crop selection, all designed to maximize the scant moisture available.

-

Deep Planting: Unlike modern methods where seeds are planted just a few inches deep, Hopi farmers plant their corn seeds up to 10-12 inches deep, sometimes even deeper. This allows the germinating seed to access moisture retained in the cooler subsoil from winter snowmelt and sporadic summer rains, protecting it from the scorching surface heat and drying winds. This technique requires immense patience and skill, as the young sprout must push its way through a foot of soil to reach the sunlight.

-

"Waffle" Gardens and Micro-Catchments: In some areas, particularly near homes, Hopi farmers create "waffle" gardens – small, sunken beds surrounded by earthen walls. These act as miniature catchments, trapping precious rainwater and directing it to the plants. Similarly, small stone check dams or brush fences are strategically placed in washes and on slopes to slow down runoff, allowing water to infiltrate the soil rather than evaporating or eroding the land.

-

Windbreaks and Soil Protection: The relentless winds of the Arizona high desert can quickly desiccate young plants and strip away topsoil. Hopi farmers combat this by leaving natural vegetation, planting trees, or constructing low brush fences on the windward side of their fields. These windbreaks reduce evaporation and prevent soil erosion, creating a more stable microclimate for their crops.

-

The Three Sisters (Trio of Life): One of the most famous and effective indigenous agricultural practices is the companion planting of corn, beans, and squash, known as the "Three Sisters." This polyculture system creates a symbiotic relationship:

- Corn provides a natural trellis for the beans to climb.

- Beans fix nitrogen from the air into the soil, enriching it for all three plants.

- Squash spreads along the ground, shading the soil to retain moisture, suppressing weeds, and its prickly leaves deter pests.

This ancient partnership ensures nutrient cycling, pest resistance, and a diverse, balanced diet for the people.

-

Heirloom Seed Saving: The Hopi have meticulously preserved and adapted their heirloom seeds for generations. These indigenous varieties, particularly the diverse strains of corn (blue, white, yellow, red, black, and variegated), are incredibly resilient and genetically diverse, having evolved over centuries to thrive in the specific local conditions. Each year, the strongest, most productive plants are selected for their seeds, ensuring the continuity of their genetic heritage and the adaptation of their crops to changing environmental conditions. This practice is a living library of agricultural knowledge, far more complex than any modern seed bank.

A Holistic Lifestyle: Beyond the Fields

Hopi farming is not an isolated activity; it is deeply interwoven with every aspect of their culture, society, and spiritual life. Planting and harvesting are communal efforts, fostering strong community bonds and intergenerational learning. Children learn from a young age to feel the soil, understand the weather patterns, and respect the cycles of nature.

Ceremonies and dances, such as the Niman Kachina (Home Dance) and the Snake Dance, are intimately tied to the agricultural cycle, expressing gratitude for rain and a bountiful harvest, and praying for the well-being of the crops and the community. The kachinas, spiritual beings, are believed to bring rain and good fortune to the people.

"When we plant, we’re not just putting a seed in the ground," explains a young Hopi woman, whose grandmother taught her how to tend the corn. "We’re planting our prayers, our hopes, our future. We sing to the corn. We talk to it. It is our family."

Challenges in a Changing World

Despite its enduring strength, Hopi traditional farming faces significant challenges in the 21st century.

- Climate Change: The most pressing threat is the increasing unpredictability of weather patterns. Prolonged droughts, earlier snowmelt, and more extreme heat events strain even the most resilient dryland techniques. "The rain used to come when it was supposed to," Lomayesva observes, "Now, who knows? It makes it harder each year."

- Economic Pressures: The younger generation often faces a choice between staying on the reservation to farm, which offers limited economic opportunities, or seeking employment in urban centers. This migration leads to a decline in the number of active farmers and a potential loss of crucial intergenerational knowledge.

- Loss of Knowledge: As elders pass on, the intricate details of planting cycles, seed selection, and spiritual protocols risk being lost if not actively passed down and embraced by the youth.

- Access to Land and Water: While the Hopi have sovereign land, disputes over water rights and the impact of external industries (like coal mining, historically) have posed threats to their traditional agricultural lands and water sources.

Preserving a Precious Legacy

In response to these challenges, there is a growing movement within the Hopi community to revitalize and preserve their traditional farming practices. Organizations like the Hopi Cultural Preservation Office and various community-led initiatives are working to:

- Educate the Youth: Programs are being developed to teach young Hopi people about their agricultural heritage, offering hands-on experience in the fields and connecting them with elders.

- Document Knowledge: Efforts are underway to document traditional farming techniques, seed varieties, and associated cultural practices to ensure their survival.

- Promote Food Sovereignty: Encouraging self-sufficiency and the consumption of traditional foods not only supports health but also reinforces cultural identity and economic independence.

- Share Wisdom: The Hopi are increasingly sharing their knowledge with the wider world, offering insights into sustainable agriculture, climate adaptation, and the profound benefits of a holistic relationship with the land.

The Hopi way of farming is more than just a historical curiosity; it is a vital, living tradition that holds immense wisdom for our contemporary world. It teaches us about resilience in the face of adversity, the profound connection between culture and environment, and the enduring power of respect for the Earth. As the sun sets over the mesas, casting long shadows across the carefully tended cornfields, the rhythmic whisper of the wind carries not just the echoes of the past, but the promise of a sustainable future, nurtured by the guardians of the desert harvest. Their fields are not just farms; they are schools, temples, and enduring symbols of a wisdom we all urgently need to learn.