Cultivating Resilience: The Enduring Wisdom of Hopi Traditional Ecological Knowledge

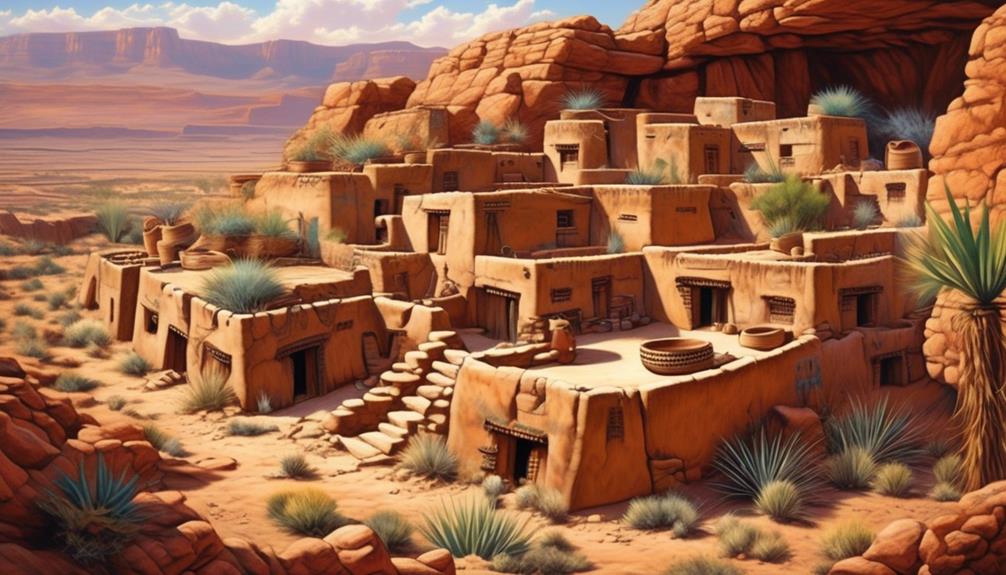

The Arizona sun beats down relentlessly on the high desert mesas, a landscape of ochre dust, ancient rock formations, and vast, open sky. For outsiders, it might seem an inhospitable place to cultivate life, let alone sustain a civilization for over a millennium. Yet, perched atop these elevated plateaus, the Hopi people have not merely survived but thrived, their very existence a living testament to a profound and enduring wisdom: Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK).

More than just a set of agricultural techniques, Hopi TEK is a holistic worldview, an intricate tapestry woven from generations of acute observation, spiritual reverence, and an unwavering commitment to reciprocity with the natural world. It is a philosophy born from the land, shaped by its challenges, and perfected through an unbroken chain of experiential learning. In an era grappling with climate change, food insecurity, and environmental degradation, the Hopi way offers not just lessons, but a vital blueprint for sustainable living.

A Sacred Covenant with the Land

The Hopi, whose name translates to "Peaceful People," have inhabited this arid region for centuries, their villages among the oldest continuously inhabited settlements in North America. Their deep connection to the land is not merely practical; it is spiritual, defining their identity and purpose. The land is seen not as a resource to be exploited, but as a living relative, a sacred entity to be nurtured and respected.

"For us, the land is our mother," explains a Hopi elder, a sentiment echoed across generations. "She provides for us, and we must care for her in return. Our farming is not just about growing food; it is about maintaining balance and harmony with all creation." This profound understanding underpins every aspect of their TEK.

Central to Hopi existence is dryland farming, an extraordinary feat of agricultural ingenuity in a region receiving an average of only 10 inches of rain annually. Unlike modern agriculture that often relies on irrigation and chemical inputs, Hopi farming is almost entirely rain-fed, a gamble against the elements that has been won consistently through meticulous observation and adaptation.

Master Farmers of the Arid Lands

The techniques employed by Hopi farmers are a marvel of sustainable engineering, honed over centuries.

1. Water Harvesting and Conservation:

Recognizing that every drop of water is precious, Hopi farmers have developed ingenious methods to capture and conserve it. Their famous "waffle gardens" are a prime example. These are small, square plots, often no more than a few feet wide, surrounded by earthen dikes that resemble the grid of a waffle. These low walls trap rainwater, allowing it to percolate slowly into the soil directly around the plant roots, minimizing runoff and evaporation.

Beyond individual plots, the Hopi strategically place rock check dams across ephemeral washes and gullies. These structures slow down flash floods, allowing sediment and moisture to accumulate, creating fertile pockets for planting and recharging groundwater. They also employ windbreaks – often rows of native plants or strategically placed rocks – to reduce wind erosion and prevent moisture loss from the soil surface.

2. Seed Diversity and Adaptation:

The Hopi are renowned for their corn, particularly the vibrant blue corn that is a staple of their diet and culture. But their seed banks hold an astonishing diversity of corn varieties – hundreds of landraces, each specifically adapted to different soil types, altitudes, and moisture conditions within their territory. Some varieties are engineered through generations of selective breeding to germinate with as little as an inch of rain, while others are more tolerant of heat or cold.

This genetic diversity is a cornerstone of their resilience. If one variety fails due to specific environmental stresses in a given year, others are likely to succeed, ensuring food security. This stands in stark contrast to the monoculture practices of industrial agriculture, which rely on a narrow genetic base and are highly vulnerable to pests, diseases, and climate shocks. The Hopi practice of communal seed saving and sharing ensures that this invaluable genetic heritage is passed down and adapted by each generation.

3. Polyculture and Companion Planting:

Hopi fields are rarely monocultures. Instead, they practice polyculture, planting corn, beans, and squash together – often referred to as "the three sisters." This ancient practice is a sophisticated form of companion planting:

- Corn provides a stalk for the beans to climb, offering structural support.

- Beans are legumes that fix nitrogen in the soil, enriching it for the corn and squash.

- Squash spreads across the ground, shading the soil to reduce evaporation, suppress weeds, and deter pests with its prickly leaves.

This synergistic relationship reduces the need for external fertilizers and pesticides, creating a self-sustaining ecosystem within the garden.

4. Reading the Landscape and Microclimates:

Hopi farmers possess an intimate knowledge of their immediate environment, observing subtle cues that escape the untrained eye. They understand the nuances of soil types, elevation, wind patterns, and sun exposure to identify optimal planting locations. A slight depression in the land might collect more moisture, making it ideal for certain crops. A south-facing slope might provide extra warmth for early germination. This ability to "read" the microclimates of their territory is a direct result of centuries of direct, hands-on experience and intergenerational knowledge transfer.

The Spiritual Fabric of TEK

For the Hopi, farming is not merely a pragmatic act of food production; it is a spiritual practice, a profound act of prayer and communion. The planting of seeds is accompanied by blessings and intentions, prayers for rain and bountiful harvests. Ceremonies and rituals are meticulously performed throughout the agricultural cycle, from planting to harvesting, connecting the physical labor to the cosmic order.

The Katsina, benevolent spiritual beings who represent the life-giving forces of the universe, are central to Hopi spiritual life and agriculture. Their presence in ceremonies reinforces the interconnectedness of humans, the natural world, and the spiritual realm, emphasizing the reciprocal relationship between effort and blessing. This spiritual dimension instills a deep sense of responsibility and gratitude towards the land and its sustenance.

"We pray for the rain, not just with words, but with our actions," a Hopi farmer might explain. "Every step we take in the field, every seed we plant, is an offering, a promise to care for what the Creator has given us."

Passing Down the Wisdom

The transmission of Hopi TEK is primarily oral and experiential. Children learn by observing, participating, and listening to their elders. From a young age, they are immersed in the rhythms of the agricultural cycle, understanding the nuances of weather patterns, soil conditions, and plant growth. Stories, songs, and ceremonies encode vast amounts of ecological information, reinforcing lessons about sustainability, resource management, and the importance of community.

This intergenerational learning ensures that the knowledge is not just memorized but deeply understood and internalized, adapting subtly over time to changing environmental conditions while preserving its core principles.

Challenges and the Enduring Relevance

Today, Hopi TEK faces significant challenges. Climate change brings more unpredictable weather patterns, prolonged droughts, and intense heatwaves, stressing even their resilient agricultural systems. External pressures, such as resource extraction (historically coal mining, which impacted their sacred waters), modern economic realities, and the lure of urban life, threaten traditional practices and the continuity of knowledge transfer.

Yet, despite these hurdles, Hopi TEK remains remarkably resilient and profoundly relevant. In a world grappling with the consequences of industrial agriculture, biodiversity loss, and climate instability, the Hopi offer a powerful alternative:

- Climate Resilience: Their dryland farming techniques provide a model for adapting to increasing water scarcity.

- Food Security: Their emphasis on seed diversity and local food production offers a blueprint for building robust, decentralized food systems.

- Environmental Stewardship: Their worldview of reciprocity and reverence for nature provides a much-needed ethical framework for human interaction with the planet.

- Biodiversity Conservation: Their preservation of diverse crop varieties is invaluable for global food security.

The Hopi people’s enduring connection to their land, cultivated through centuries of meticulous observation, spiritual reverence, and practical innovation, offers a profound lesson for all of humanity. Their Traditional Ecological Knowledge is not a relic of the past, but a living, evolving testament to the power of harmony with nature – a vital guide for navigating the challenges of the present and cultivating a more sustainable future. As the Hopi have always understood, true resilience comes not from dominating nature, but from dancing with it, patiently and respectfully, in the ancient rhythms of the earth.