Certainly, here is an article in English, written in a journalistic style, addressing the question "How many Native American tribes?" and aiming for approximately 1200 words.

The Enduring Tapestry: Unpacking the Complex Question of Native American Tribal Identity

On the surface, the question "How many Native American tribes are there?" seems straightforward. A quick search might yield a number, perhaps around 574. Yet, like a single thread attempting to define an intricate tapestry, this figure only begins to hint at the profound historical, cultural, and political complexities that define Indigenous identity in the United States. To truly understand the "how many," one must embark on a journey through centuries of profound change, resilience, and the enduring fight for self-determination.

The simple answer, if there ever was one, is that the number is fluid, multifaceted, and constantly evolving, shaped by history, law, and the unwavering spirit of Indigenous peoples themselves. It is a number that reflects not just current administrative counts, but the ghosts of countless nations that vanished, the tenacity of those who survived, and the ongoing struggles of communities striving for recognition and revitalization.

Before the Count: A Continent of Nations

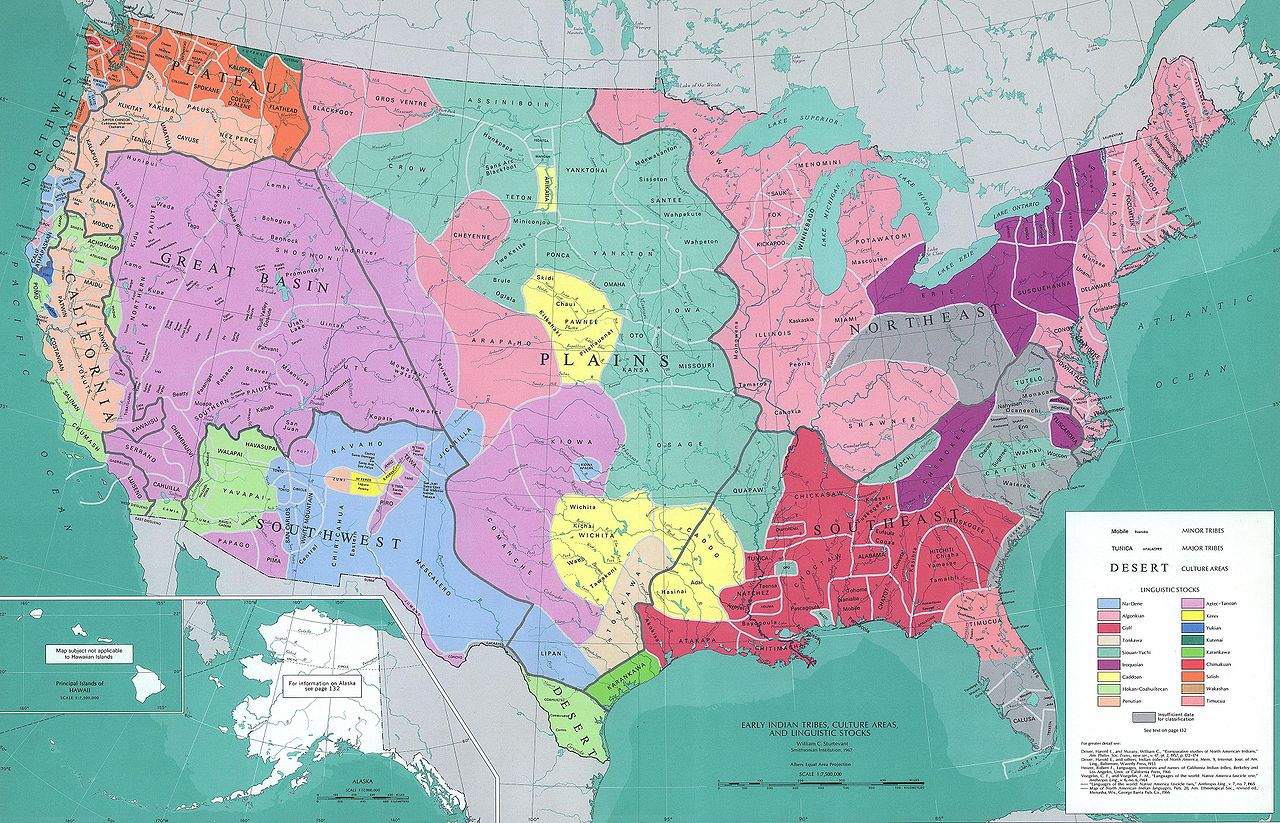

Before European contact, the lands now known as the United States were home to millions of people, organized into thousands of distinct nations, bands, and communities. From the agricultural societies of the Southeast, like the Cherokee, Choctaw, and Creek, to the nomadic hunters of the Great Plains, such as the Lakota, Cheyenne, and Crow, each group possessed its own intricate governance, spiritual beliefs, economic systems, and, critically, language.

Estimates suggest that at the time of Columbus’s arrival in 1492, there were between 300 and 500 distinct Indigenous languages spoken across North America. This linguistic diversity alone underscores the vast array of cultures and political entities that flourished. There was no single "Native American" identity; instead, there was a mosaic of sovereign peoples, each with their unique traditions and relationships to their ancestral lands. The concept of a single, unified "tribe" as understood by European colonizers often failed to grasp the nuanced social and political structures of Indigenous societies, which frequently involved confederacies, clans, and fluid alliances.

The Cataclysm of Contact and the Shaping of "Tribes"

The arrival of European colonizers unleashed a cataclysm. Disease, warfare, forced removal, and the deliberate policies of assimilation decimated populations and dismantled traditional ways of life. The infamous Trail of Tears, the Sand Creek Massacre, and countless other atrocities serve as stark reminders of this period of profound loss and trauma. As European powers, and later the United States, sought to control land and resources, they often imposed their own definitions of what constituted a "tribe" for the purposes of treaties, land cessions, and, eventually, the establishment of reservations.

The reservation system, initially conceived as a means of separating Indigenous peoples from settlers, inadvertently played a role in consolidating diverse bands and remnants of nations onto delimited territories. This often led to the formation of new political entities or the merging of disparate groups, further complicating the pre-existing Indigenous landscape. The Dawes Act of 1887, which aimed to break up communal tribal lands into individual allotments, was another destructive policy, eroding tribal sovereignty and further fragmenting Indigenous communities.

The Era of Federal Recognition: A Bureaucratic Filter

The modern understanding of "how many tribes" is largely tied to the concept of federal recognition. This is the formal acknowledgment by the United States government of a tribe’s status as a sovereign nation, with a government-to-government relationship with the U.S. It grants access to certain federal services, funding, and, crucially, reinforces a tribe’s inherent right to self-governance.

The process for achieving federal recognition, primarily managed by the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) through its Office of Federal Acknowledgment, is notoriously arduous, expensive, and time-consuming. Tribes seeking recognition must provide extensive historical, genealogical, and anthropological evidence demonstrating continuous existence as an identifiable community, political influence or authority over their members, and descent from a historical tribe. The burden of proof is immense, often requiring centuries of documentation that may have been lost or destroyed due to historical trauma and displacement.

As of late 2023, there are 574 federally recognized Native American tribes in the United States. This number includes tribes in the contiguous 48 states and Alaska Native villages and corporations. It is the most commonly cited figure when discussing the number of tribes, but it represents only a portion of the Indigenous communities that exist.

Beyond Federal Recognition: State-Recognized and Unrecognized Tribes

The federal list, while significant, is not exhaustive. Many Indigenous communities exist without federal recognition, and they fall into several categories:

-

State-Recognized Tribes: Some tribes are recognized by individual state governments but not by the federal government. This recognition often grants them certain state-level benefits and legal standing within that state, but it does not confer the same sovereign status or federal benefits. States like California, Virginia, and Massachusetts have their own processes for recognizing tribes, and the number fluctuates. For instance, Virginia formally recognized six tribes in 2017, and several of those later achieved federal recognition. This category adds dozens more entities to the overall count of existing Indigenous communities.

-

Unrecognized Tribes (Self-Identified): Perhaps the largest and most complex category consists of hundreds of Indigenous communities that are neither federally nor state-recognized but maintain their identity, culture, and often, a communal land base. These groups often refer to themselves as tribes, bands, or nations, based on their own traditions and history. They may be communities whose historical records were destroyed, whose ancestors were not signatories to treaties, or whose continuous existence was disrupted by forced assimilation policies to the extent that they cannot meet the stringent federal recognition criteria. They continue to fight for acknowledgment, asserting their inherent sovereignty. Their exact number is impossible to ascertain, as it relies on self-identification and community cohesion rather than external validation.

The Dark Chapter of Termination and the Dawn of Restoration

To further complicate the count, one must consider the devastating mid-20th-century policy of "termination." From the 1940s to the 1960s, the U.S. government pursued policies aimed at assimilating Native Americans into mainstream society by terminating the federal government’s relationship with tribes. Over 100 tribes were "terminated," meaning their federal recognition, treaty rights, and access to federal services were revoked. Their lands were often sold off, and their communities left in destitution.

The Menominee Tribe of Wisconsin is a prominent example. Terminated in 1961, they lost their reservation and tribal status, leading to severe economic hardship. However, through tireless activism and a powerful political movement, the Menominee achieved restoration of their federal recognition in 1973. This marked a turning point, ushering in the era of "self-determination."

Since then, many terminated tribes have successfully campaigned for their federal recognition to be restored, but not all have. The existence of these formerly recognized tribes, some of which are still fighting for restoration, adds another layer to the historical count and underscores the fragility of recognition itself.

Beyond the Number: The Enduring Spirit of Sovereignty

While the numbers are important for legal and political standing, they fail to capture the full scope of Indigenous America. The sheer act of counting, a colonial impulse, can inadvertently diminish the richness and diversity of Indigenous identity. For many Native people, tribal identity is not conferred by a government document but by ancestry, culture, language, kinship, and a deep connection to their ancestral lands and traditions.

As Kevin Gover, a citizen of the Pawnee Nation and former Director of the National Museum of the American Indian, stated, "Our governments may recognize a tribe or not, but the people remain." This sentiment highlights that the existence of a people, their culture, and their history transcends bureaucratic categories.

Today, federally recognized tribes exercise inherent sovereignty, meaning they possess the power to govern themselves. They operate their own police forces, court systems, schools, and healthcare facilities. They manage their lands and resources, engage in economic development (which famously includes casinos, but also diverse enterprises from tourism to technology), and negotiate with federal and state governments on a nation-to-nation basis.

This resurgence of tribal sovereignty is a testament to the resilience of Indigenous peoples. Despite centuries of adversity—disease, war, forced removal, assimilation policies, and economic marginalization—Native American cultures, languages, and governance structures endure and are experiencing vibrant revitalization. Tribes are leading efforts in environmental protection, language preservation, cultural education, and the fight for social justice.

Conclusion: A Story of Resilience and Ongoing Identity

The question of "how many Native American tribes are there?" is not a simple numerical query, but a doorway into a profound narrative of survival, adaptation, and unwavering identity. The official count of 574 federally recognized tribes provides a crucial legal and political framework, but it is merely the tip of the iceberg. Beneath that number lies a vast and diverse landscape of state-recognized communities, self-identified nations still fighting for their place, and the echoes of countless groups that vanished but whose legacy lives on in the land and in the hearts of their descendants.

The true answer is that Indigenous America is not a static collection of discrete entities but a dynamic, living tapestry woven from thousands of threads, each representing a distinct history, culture, and vision for the future. It is a testament to the enduring power of Indigenous peoples to define themselves, to govern themselves, and to continue their journey on their ancestral lands, regardless of any external count. Understanding this complexity is essential for truly appreciating the depth and richness of Native American heritage and the ongoing struggles for justice and self-determination.