The Unhealed Scar: The Enduring Legacy of the Indian Removal Act

Few acts in American history cast as long and dark a shadow as the Indian Removal Act of 1830. Signed into law by President Andrew Jackson, it codified a policy that had long been brewing: the forced relocation of Native American nations from their ancestral lands in the southeastern United States to territories west of the Mississippi River. What followed was not merely a geographic displacement, but a catastrophic unraveling of cultures, economies, and lives, leaving a wound that continues to fester in the American consciousness and within the hearts of Indigenous peoples.

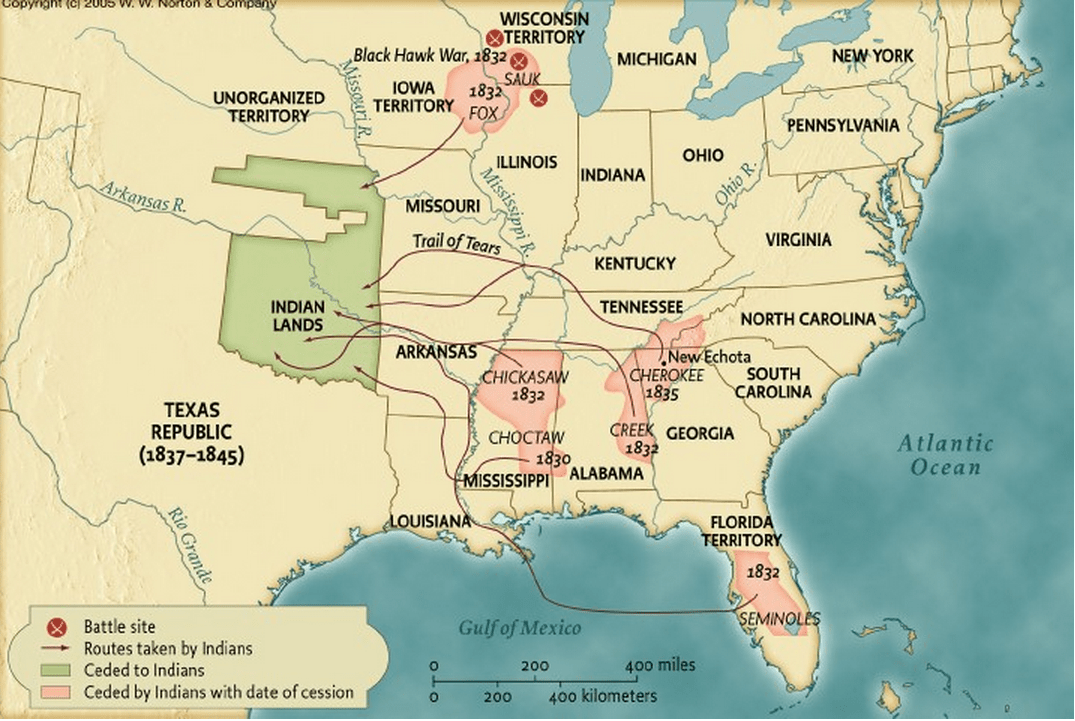

The story of the Indian Removal Act is often simplified to the "Trail of Tears," a singular event. Yet, it was a complex, brutal process that impacted multiple sovereign nations – the Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seminole – collectively known as the "Five Civilized Tribes" due to their adoption of many Euro-American customs, including written languages, constitutional governments, and farming practices. This very adoption, ironically, made their removal even more insidious, as it undermined the prevailing narrative that they were "savages" incapable of self-governance or land ownership.

The Pretext and the Reality

By the early 19th century, the burgeoning United States, fueled by the cotton boom and the doctrine of Manifest Destiny, cast an covetous eye on the fertile lands of the Southeast. Georgia, in particular, exerted immense pressure on the federal government to remove the Cherokee, whose territory lay within its claimed borders. The discovery of gold on Cherokee land in 1829 only intensified the clamor for their removal.

President Andrew Jackson, a veteran of wars against Native Americans and a staunch advocate for states’ rights, was the architect of the Act. He argued that removal was for the "benefit" and "preservation" of Native Americans, protecting them from the corrupting influence of white society and allowing them to thrive in their own separate territory. In his second annual message to Congress in 1830, Jackson famously asserted, "All preceding experiments for the improvement of the Indians have failed. It is, therefore, a question, whether a civilized community can be in a state of prosperity, and happiness, and improvement, and at the same time aboriginal tribes be allowed to remain as a distinct people in their midst." This rhetoric conveniently masked the true motives: land greed and racial prejudice.

The Act authorized the president to negotiate treaties for the exchange of Indian lands in the east for lands in the west. While framed as "voluntary removal," the reality was far from it. For many tribes, the negotiations were coercive, backed by the implicit threat of military force and the explicit denial of their sovereignty by state governments.

The Immediate Catastrophe: The Trail of Tears and Beyond

The consequences of the Indian Removal Act were immediate and devastating.

- The Choctaw (1831-1833): They were the first to be forcibly removed under the Act. Thousands perished from cholera, exposure, and starvation during their winter march from Mississippi to Oklahoma. A Choctaw leader, after arriving in their new lands, described the experience as a "trail of tears and death," giving the eventual Cherokee removal its enduring name.

- The Creek (1836): Following a period of intense pressure, including state laws that effectively stripped them of their rights and land, many Creek were forcibly rounded up by the U.S. Army and marched west in chains, enduring immense suffering.

- The Chickasaw (1837-1838): Unlike other tribes, the Chickasaw negotiated a financial settlement for their lands and largely managed their own removal. However, they still faced the hardship of resettlement and the loss of their ancestral homes.

- The Cherokee (1838-1839): Their story is perhaps the most well-known and tragic. Despite adopting a written language (Sequoyah’s syllabary), publishing a newspaper (the Cherokee Phoenix), and successfully challenging Georgia’s laws in the Supreme Court (Worcester v. Georgia, 1832), their fate was sealed. Chief Justice John Marshall ruled in favor of the Cherokee, stating that Georgia had no jurisdiction over their lands. However, President Jackson famously defied the ruling, allegedly stating, "John Marshall has made his decision; now let him enforce it!" A minority faction of the Cherokee, the Treaty Party, signed the Treaty of New Echota in 1835 without the consent of the principal chief or the majority of the nation. This fraudulent treaty was used as the legal justification for their removal.

In the brutal winter of 1838-1839, approximately 16,000 Cherokee were rounded up by federal troops and forced to march 1,200 miles from their homes in Georgia, Tennessee, North Carolina, and Alabama to Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma). Lacking adequate food, clothing, and shelter, an estimated 4,000 men, women, and children died from disease, starvation, and exposure. Entire families perished, and bodies were often left unburied along the route. It was, as one survivor recounted, "a lamentable and heart-rending spectacle."

- The Seminole (1835-1842): Their resistance led to the Second Seminole War, one of the longest and costliest Indian wars in U.S. history. Led by figures like Osceola, the Seminole fought fiercely against removal, utilizing the Florida Everglades as their stronghold. While many were eventually captured and removed, a significant number managed to evade capture and remain in Florida, a testament to their resilience.

The Long-Term Scars: Beyond the March

The immediate horrors of the forced marches were just the beginning. The Indian Removal Act unleashed a cascade of long-term consequences that continue to shape the lives of Native Americans today:

- Loss of Land and Resources: This was the most fundamental consequence. Tribes lost millions of acres of ancestral land, including sacred sites, burial grounds, and vital hunting and farming territories. This dispossession severed their deep spiritual, cultural, and economic ties to the land, which had sustained them for millennia. The new lands in Indian Territory were often vastly different ecologically, requiring immense adaptation and leading to further inter-tribal conflicts over resources.

- Cultural Disruption and Erosion: Removal was an assault on identity. Traditional governance structures were uprooted, languages suppressed, and spiritual practices challenged. While tribes demonstrated incredible resilience in preserving their cultures, the forced relocation fragmented communities, making the transmission of knowledge and traditions more difficult. The subsequent establishment of boarding schools, designed to "civilize" Native children by stripping them of their culture, only amplified this disruption.

- Economic Devastation: The agrarian societies of the Five Civilized Tribes were utterly destroyed. Farms, homes, and possessions were abandoned or stolen. Once self-sufficient, many tribes were plunged into poverty and became dependent on often meager and unreliable federal annuities and supplies, which were frequently mismanaged or stolen by corrupt agents. This created a cycle of economic disadvantage that persists in many Native communities.

- Psychological and Intergenerational Trauma: The experience of removal left deep psychological wounds. Survivors carried the trauma of witnessing unimaginable suffering, loss of family, and profound betrayal. This historical trauma has been passed down through generations, contributing to higher rates of poverty, substance abuse, and mental health issues in Native American communities today. The loss of trust in the U.S. government became deeply embedded, a justifiable skepticism born from broken treaties and violent displacement.

- Erosion of Sovereignty and Treaty Rights: The Indian Removal Act set a dangerous precedent, demonstrating that even Supreme Court rulings could be ignored when it came to Native American rights. It fundamentally undermined the concept of tribal sovereignty, treating Native nations not as independent entities but as obstacles to be removed. This laid the groundwork for future federal policies that further diminished tribal self-governance and treaty obligations.

- Internal Divisions: The pressure of removal sometimes led to tragic internal divisions within tribes, as seen with the Cherokee Treaty Party. These divisions, born of desperation and conflicting strategies for survival, left lasting scars and mistrust within communities.

A Living Legacy

The Indian Removal Act is not merely a chapter in a history book; it is a living wound in the American narrative. The descendants of those who endured the forced marches continue to grapple with its legacy. Contemporary issues facing Native American communities – including poverty, health disparities, land disputes, and the ongoing fight for self-determination – are inextricably linked to this foundational act of dispossession.

Yet, despite the profound injustices, the story of the Indian Removal Act is also one of incredible resilience. Native nations survived. They rebuilt their communities in new lands, adapted, and fought tirelessly to preserve their languages, cultures, and identities. Today, vibrant Native American nations continue to advocate for their rights, reclaim their narratives, and revitalize their cultures, serving as a powerful testament to the enduring spirit of Indigenous peoples.

Understanding the Indian Removal Act is crucial for comprehending the complex relationship between Native Americans and the U.S. government. It serves as a stark reminder of the devastating consequences of unchecked expansionism, racial prejudice, and the abuse of power. Only by confronting this painful past can the nation begin the long and difficult process of healing and reconciliation.