The Enduring Architects of Peace: Unpacking the Iroquois Confederacy’s Proto-Federal Masterpiece

Centuries before the United States forged its federal system, a sophisticated, enduring political structure flourished in the woodlands of what is now northeastern North America. It was the Haudenosaunee, or the People of the Longhouse, widely known as the Iroquois Confederacy – a formidable alliance of nations bound by a shared vision of peace, unity, and collective governance. Far from a collection of warring tribes, the Iroquois built a system of checks and balances, consensus-driven decision-making, and distributed power that astounded early European observers and continues to fascinate scholars today.

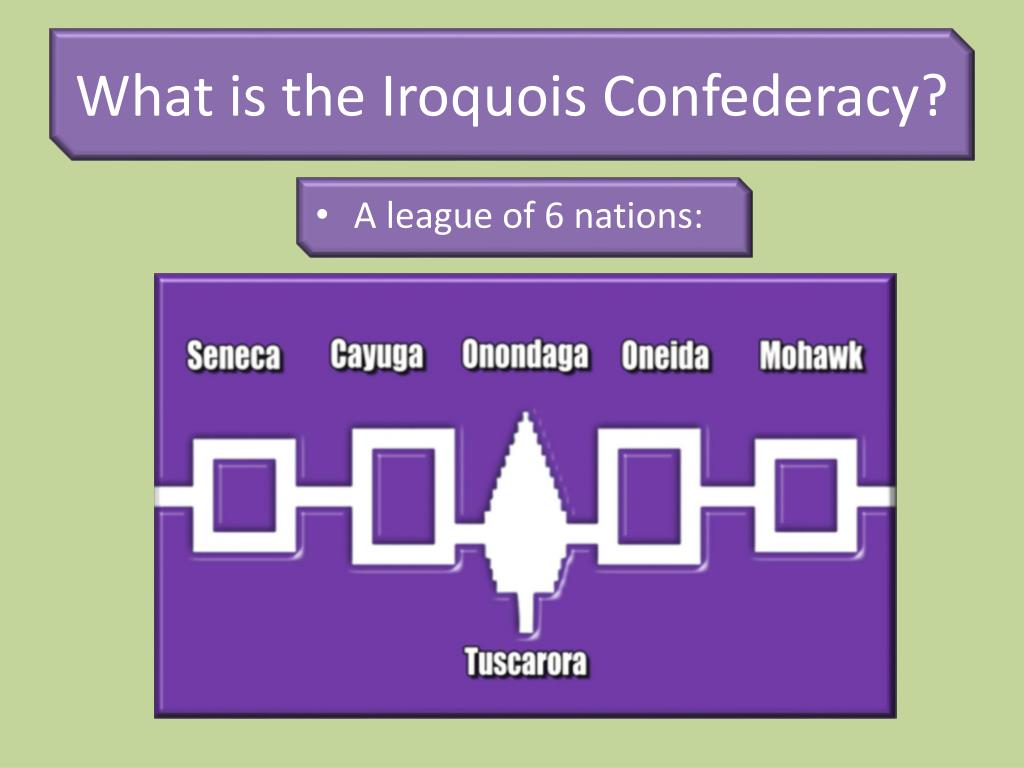

At its heart lay the Great Law of Peace (Gayanashagowa), an unwritten but meticulously memorized constitution passed down through generations. Its origins are steeped in legend, attributed to the divine figure known as the Peacemaker, Hiawatha, and the influential Clan Mother, Jigonsaseh. Before the Great Law, the five founding nations – the Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, and Seneca – were embroiled in ceaseless, brutal warfare. The Peacemaker’s message was revolutionary: unity through a shared commitment to peace, righteousness, and power. He envisioned a society where disputes were resolved through deliberation, not destruction, and where the welfare of the people, including future generations, was paramount.

The Great Law transformed a landscape of conflict into a beacon of stability. It established the Confederacy as a political entity, not just a military alliance, and laid out the framework for its governance. The symbol of this new era was the Tree of Peace, under which all weapons of war were buried, its roots extending to the four directions, inviting all peoples to join the circle of peace.

The Grand Council: A Bicameral Symphony of Nations

The linchpin of the Iroquois political structure was the Grand Council of Chiefs (Hoyaneh), a body comprising 50 sachems or male chiefs, each representing a specific clan and nation. These chiefs were not elected in the modern sense; rather, they were nominated by the Clan Mothers of their respective lineages, a testament to the profound power women wielded within Haudenosaunee society.

The Grand Council was arranged not by population, but by the symbolic roles of the nations. The Onondaga, as the "Keepers of the Central Fire," held 14 chiefs and served as the Confederacy’s geographic and spiritual heart, where the Grand Council traditionally met. The Mohawk and Seneca were considered the "Older Brothers" or "Keepers of the Eastern and Western Doors," respectively, holding 9 and 8 chiefs. The Oneida and Cayuga were the "Younger Brothers," with 9 and 10 chiefs. Later, in the early 18th century, the Tuscarora Nation was admitted into the Confederacy, becoming the "Sixth Nation" but without its own chiefs on the Grand Council, instead being represented by the Oneida.

This arrangement facilitated a unique and effective system of deliberation often described as proto-bicameral or even multi-cameral. Decisions were not made by simple majority vote, but through a painstaking process of consensus-building:

- Initiation: A proposal would typically originate with the "Older Brothers" (Mohawk and Seneca). The Seneca would deliberate first, then pass their decision to the Mohawk. If they agreed, the proposal would move forward. If not, it would be sent back for further discussion until they reached a unified position.

- Transmission to Younger Brothers: Once the Older Brothers reached consensus, the proposal would be passed to the "Younger Brothers" (Oneida and Cayuga). They, too, would deliberate internally and then collectively.

- Onondaga Review: Finally, the unified decision of the Younger Brothers would be presented to the Onondaga chiefs, the "Keepers of the Central Fire." The Onondaga acted as a kind of supreme court or final arbiter. They reviewed the proposal, ensuring it aligned with the Great Law of Peace and the collective good. If they found any flaw, they could send it back to the Younger Brothers, who would then send it back to the Older Brothers for reconsideration. This iterative process continued until all nations, through their designated representatives, reached unanimous consent.

This system, though seemingly slow, ensured that every voice was heard, every perspective considered, and that any decision truly reflected the collective will of the Confederacy. It was a powerful check against tyranny and impulsive action, demanding patience, diplomacy, and a deep commitment to shared values.

The Matriarchal Backbone: The Power of Clan Mothers

Perhaps the most distinctive and arguably radical aspect of the Iroquois political structure, especially when viewed through a Eurocentric lens, was the pivotal role of women. Haudenosaunee society was matrilineal, meaning descent, property, and clan affiliation were traced through the mother’s line. This gave women, particularly the Clan Mothers (Gaihwiio), immense power and influence.

Clan Mothers were the custodians of tradition, the keepers of clan history, and the moral compass of their communities. Their responsibilities were vast:

- Chief Selection and Deposition: They held the sole authority to nominate the male chiefs (Hoyaneh) for the Grand Council. Crucially, they also possessed the power to "de-horn" a chief – to remove him from office – if he failed to uphold his duties, acted dishonorably, or violated the Great Law. This power served as a vital check on male authority, ensuring accountability.

- Advisors and Veto Power: Clan Mothers advised the chiefs on all matters, and their counsel was taken seriously. In some interpretations, they held a de facto veto power over decisions if they believed the chiefs were straying from the principles of the Great Law or acting against the welfare of the people.

- Custodians of the Land and Longhouse: Women controlled the communal longhouses, the agricultural lands, and the distribution of food. Their control over resources provided a substantial basis for their political authority.

- Peace and War: While men were the warriors, Clan Mothers had a significant say in decisions of war and peace, often acting as advocates for peaceful resolution. They could initiate peace negotiations and, notably, had the final say on the fate of captives.

As Audrey Shenandoah, an Onondaga Clan Mother, once stated, "The Creator gave the women the responsibility to give life. So, therefore, we are the life givers. We are the ones that must protect the life." This deep respect for women as life-givers translated directly into their unparalleled political and social power within the Confederacy.

Local Governance and Individual Rights

Below the Grand Council, each nation maintained its own internal council, composed of its own chiefs and Clan Mothers. These councils managed local affairs, resolved disputes, and served as conduits for communication between the people and the Grand Council. The clan system itself provided a robust social safety net and a framework for identity. Every individual belonged to a clan, which extended across the nations, fostering inter-nation unity and preventing internal strife.

While the Great Law of Peace focused on collective well-being, it also inherently protected individual rights. The emphasis on consensus meant that individual voices were valued. The right to free speech was paramount, as open deliberation was essential for reaching agreement. There were no jails in the traditional Iroquois system; disputes were resolved through community mediation and restitution, emphasizing rehabilitation over punishment.

Legacy and Enduring Influence

The Iroquois Confederacy’s political structure proved remarkably resilient. It allowed the Haudenosaunee to maintain their sovereignty and influence for centuries, navigating complex relationships with European colonial powers, often playing them against each other. Their confederacy served as a formidable barrier to colonial expansion and a powerful model of indigenous self-governance.

The question of whether the Iroquois Confederacy directly influenced the drafting of the U.S. Constitution remains a subject of academic debate. While some scholars, notably Bruce E. Johansen, argue for significant influence, pointing to parallels in federalism, separation of powers, and checks and balances, others caution against overstating a direct causal link. However, what is undeniable is that many of the Founding Fathers, including Benjamin Franklin, were familiar with the Iroquois system, having observed its effectiveness firsthand during treaty councils. Franklin, for instance, explicitly urged the colonies to unite in a similar fashion, remarking on the Iroquois’ strength through unity. Regardless of the direct influence, the Iroquois system stands as an independent testament to the human capacity for sophisticated political organization.

Today, the Iroquois Confederacy continues to exist as a vibrant political entity. The Grand Council still meets, deliberating on issues affecting the Haudenosaunee people, from land rights and environmental protection to cultural preservation. It is not merely a historical artifact; it is a living, breathing testament to an ancient and profoundly effective form of governance that prioritizes peace, consensus, and the well-being of all, demonstrating that a true democracy can be built on principles far older than any written constitution. The Iroquois Confederacy offers a powerful lesson in enduring self-governance, a model of political genius born from the spirit of unity under the sacred Tree of Peace.