The Unseen Tapestry: Unveiling the Enduring Spiritual Heart of the Iroquois

In the vast, verdant landscapes of what is now northeastern North America, where ancient forests whisper tales of time and rivers carve paths through enduring rock, live the Haudenosaunee – the People of the Longhouse, more commonly known as the Iroquois Confederacy. Far more than a formidable political and military alliance, their civilization is underpinned by a profound and intricate spiritual worldview, a vibrant tapestry woven from reverence for the natural world, a deep sense of gratitude, and an unwavering commitment to balance. This isn’t a static, historical curiosity, but a living, breathing set of beliefs that continues to shape the lives of the Haudenosaunee today.

At the core of Iroquois spirituality lies the concept of a Great Spirit, or Creator, often referred to as Ha-wen-ne-yu, the Master of Life. This supreme being is not a distant, judgmental deity, but an omnipresent force responsible for the creation of all life and the natural order. Complementing this is the understanding of Orenda, a spiritual power or energy that permeates everything – from the smallest insect to the tallest tree, from a flowing river to a human thought. This belief fosters a deep sense of interconnectedness, where humans are not masters of the earth, but an integral part of its grand design.

The Haudenosaunee creation story vividly illustrates this foundational belief. It speaks of Sky Woman, who fell from a hole in the Sky World, landing on the back of a giant turtle – thus forming Turtle Island, the North American continent. From her, life on Earth began. Her daughter gave birth to twin sons: Teharonhiawagon (Sapling), the Good Mind, who shaped the world with beauty and harmony, creating rivers, fertile lands, and beneficial plants and animals; and Sawiskera (Flint), the Evil Mind, who introduced challenges, mountains, rapids, and less benevolent creatures, creating the necessary balance for growth and resilience. This duality is not a battle between good and evil in the Western sense, but a recognition that both aspects are essential for life’s richness, teaching adaptability and the constant striving for equilibrium.

The Thanksgiving Address: A Daily Act of Gratitude

Perhaps the most potent and enduring expression of Iroquois spirituality is the Ohén:ton Karihwatéhkwen, or "The Words That Come Before All Else," universally known as the Thanksgiving Address. This isn’t merely a prayer; it is a profound philosophical statement and a ritual of gratitude that opens every significant Haudenosaunee gathering, from council meetings to ceremonies, and is often recited privately by individuals each morning.

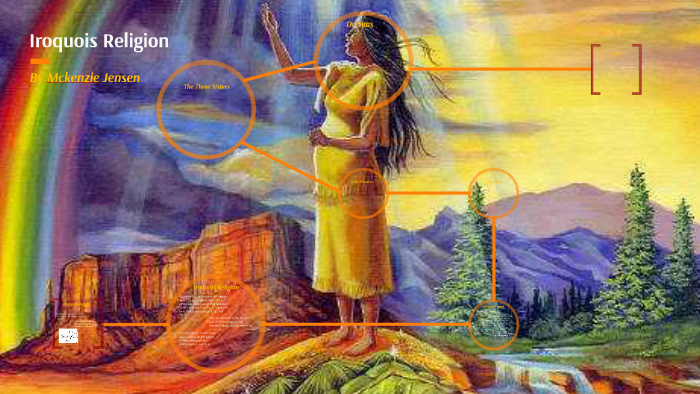

The Address systematically acknowledges and offers thanks to all elements of the natural world, starting with Mother Earth, then moving through the waters, fish, plants, food plants (especially the Three Sisters: Corn, Beans, and Squash), wild animals, trees, birds, the Four Winds, the Thunderers, the Sun, Grandmother Moon, the Stars, the enlightened teachers (like the Peacemaker, Deganawidah), and finally, the Creator.

As a speaker recites the Address, often over many minutes or even an hour, they invite the audience to affirm their gratitude with the collective response, "Nia:wen" (Thank you). This practice instills a deep sense of humility and responsibility. "We give thanks to our Mother, the Earth," the Address typically begins. "She supports our feet and gives us all we need for life. We thank the waters of the Earth, the rivers, streams, lakes, and oceans, for quenching our thirst and cleansing us. We give thanks to the plants, who provide us with food and medicine." This constant articulation of gratitude fosters a reciprocal relationship with nature, where taking is always balanced by giving thanks and acting as a steward.

The Cycles of Life: Ceremonies and the Longhouse

Iroquois spiritual life is intimately tied to the cycles of the seasons, reflecting the agricultural roots of their society. A series of seasonal ceremonies mark the year, each an occasion for communal thanksgiving, renewal, and connection to the spiritual realm.

- Midwinter Ceremony (Ginodaganih): The most significant, celebrated in late January or early February, marking the New Year. It is a time for renewing the mind, forgiving transgressions, reconfirming the Gaiwiio (Good Message), and offering tobacco to send thoughts and wishes to the Creator. Dreams are shared and interpreted, and the False Face Society may perform healing rituals.

- Maple Ceremony: Celebrated when the maple sap begins to flow, giving thanks for the sweet lifeblood of the trees.

- Strawberry Ceremony: A joyous celebration of the first berry, seen as the "leader of all fruits," and a symbol of the heart.

- Green Corn Ceremony: A major harvest festival, giving thanks for the bounty of the corn, beans, and squash, and celebrating the community’s sustenance.

- Harvest Ceremony: A final thanksgiving for all the gifts of the year.

These ceremonies, along with daily life, revolve around the Longhouse, the traditional communal dwelling and the heart of Haudenosaunee culture and spirituality. More than just a shelter, the Longhouse is a living symbol of their interconnectedness. Its elongated structure, with doors at either end, represents the unity of the Confederacy’s nations. Within its walls, ceremonies are held, councils convene, and the spiritual teachings are passed down through generations. It is here that the Gaiwiio, or the Good Message, is periodically recited in its entirety – a testament to the enduring power of oral tradition.

The Gaiwiio: A Message of Renewal

In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, the Haudenosaunee faced immense challenges: devastating wars, loss of land, disease, and the corrosive influence of alcohol introduced by European settlers. Their traditional way of life was under severe threat. It was during this period of crisis that a Seneca prophet named Ganioda’yo (Handsome Lake) received a series of powerful visions from the Creator’s messengers.

These visions, which began in 1799, formed the Gaiwiio, a new code of ethics and spiritual teachings. Handsome Lake’s message was one of moral and spiritual revitalization. It called for temperance, the rejection of witchcraft, the preservation of traditional ceremonies, respect for elders, and the importance of family and community. While incorporating some elements observed from Christianity, the Gaiwiio firmly re-established core Haudenosaunee values and provided a spiritual anchor for a people struggling to adapt to a rapidly changing world. It became a guiding principle for many Longhouse communities, helping them to retain their identity and spiritual practices through centuries of immense pressure.

Dreams, Healing, and Sacred Societies

Dreams hold significant spiritual weight in Iroquois culture. They are believed to be messages from the spirit world, revealing one’s inner desires, spiritual needs, or even prophecies. It is crucial to acknowledge and fulfill the desires expressed in dreams, as suppressing them could lead to illness or misfortune. Communal dream interpretation and fulfillment are an important part of ceremonies like the Midwinter Festival, fostering individual and collective well-being.

Healing is also deeply spiritual. Illness is often seen as an imbalance, a disharmony between the individual and the spiritual or natural world. Traditional healers utilize medicinal plants, ceremonies, and the power of specific sacred societies to restore balance.

One of the most widely known, though often misunderstood, is the False Face Society (Goihgoya:goh). Members wear carved wooden masks that represent various forest spirits and use rattles made of turtle shells. They perform healing rituals for specific ailments, especially those related to spiritual distress or possession by malevolent spirits. The masks themselves are considered living entities, imbued with spiritual power, and are treated with immense respect. It is crucial to understand that these are not theatrical performances, but sacred healing practices, rooted in a deep connection to the spirit world.

Enduring Wisdom in a Modern World

Despite centuries of colonialism, assimilation policies, and the erosion of traditional territories, Iroquois spiritual beliefs have proven remarkably resilient. They continue to be practiced in Longhouses across Haudenosaunee communities in New York, Ontario, and Quebec.

The wisdom embedded in their spiritual traditions offers profound insights for the modern world. The Thanksgiving Address, with its systematic gratitude for every part of the ecosystem, provides a powerful model for environmental stewardship and sustainable living. The emphasis on balance, reciprocity, and interconnectedness challenges anthropocentric views and promotes a harmonious relationship with nature. The Gaiwiio’s call for moral integrity and community strength speaks to the enduring human need for purpose and belonging.

In an era grappling with climate change, social fragmentation, and a search for meaning, the Haudenosaunee spiritual path offers a timeless message: that true wealth lies not in accumulation, but in gratitude; that strength comes from unity and balance; and that the spiritual heartbeat of humanity is inextricably linked to the pulse of the Earth itself. The unseen tapestry of Iroquois spirituality continues to weave its patterns, enriching not only the lives of the Haudenosaunee, but offering profound lessons for all who seek harmony with the world around them.