Echoes in Every Stitch: The Enduring Legacy of Iroquois Traditional Arts

By [Your Name/Journalist’s Name]

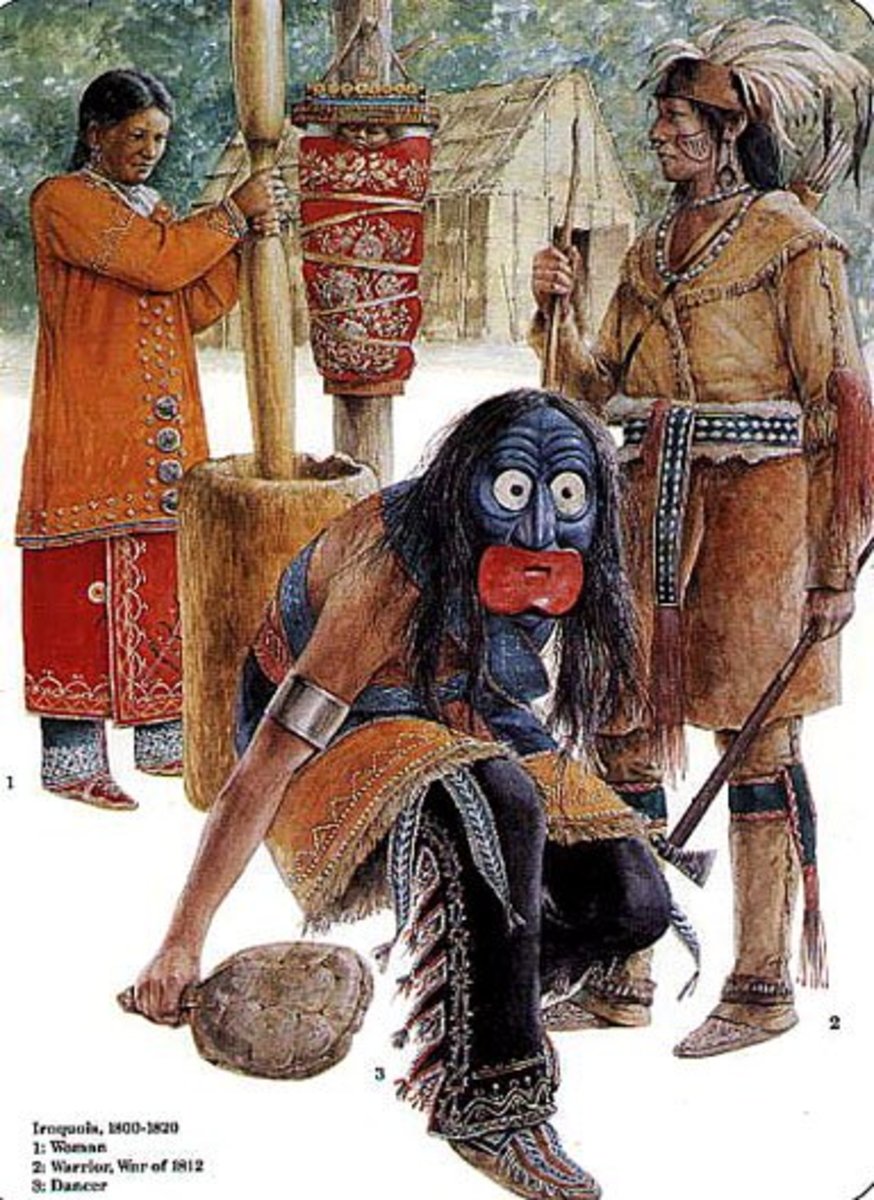

In the verdant heartlands stretching from what is now New York State across parts of Ontario and Quebec, a vibrant cultural tapestry has been woven for millennia. This is the ancestral territory of the Haudenosaunee, or "People of the Longhouse," commonly known as the Iroquois Confederacy. Far more than mere aesthetic objects, their traditional arts are living chronicles, imbued with spiritual significance, historical memory, and the profound wisdom of their ancestors. From the intricate beadwork that shimmers with stories to the sacred masks carved from living trees, Haudenosaunee art is a testament to resilience, a continuous dialogue between past and present, and a powerful assertion of identity.

The Haudenosaunee Confederacy, comprising the Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, Seneca, and Tuscarora Nations, forged a democratic alliance long before European contact. Their philosophy, encapsulated in the Great Law of Peace (Gayanashagowa), emphasizes harmony, respect for nature, and collective well-being. These core values are not abstract principles but are tangibly expressed and reinforced through their artistic traditions. "For our people," explains Tekarontake, a Mohawk elder and artist, "art is not separate from life. It is life. Every design, every material, every technique carries a piece of our history, our ceremonies, and our connection to the Creator and the land."

Wampum: Threads of Diplomacy and Memory

Perhaps no art form better exemplifies the multi-faceted role of Haudenosaunee creation than wampum. Crafted from the polished shells of quahog clams (purple beads) and whelk shells (white beads), wampum belts were not currency, as often mistakenly portrayed, but rather sacred documents, diplomatic instruments, and mnemonic devices. Each bead, meticulously strung and woven into intricate patterns, represented agreements, treaties, historical events, and even laws.

The Two Row Wampum Belt, for instance, a foundational treaty between the Haudenosaunee and Dutch settlers in 1613, features two parallel rows of purple beads on a white background. It symbolizes two distinct nations, each navigating their own vessel (one a canoe, one a ship), traveling side-by-side down the river of life, never interfering with the other. The white background represents peace, friendship, and respect. As Onondaga Faithkeeper Oren Lyons often articulates, "Wampum belts are living documents. When we bring them out, we are not just looking at history; we are reliving the commitments and responsibilities they embody." They were read aloud during councils, ensuring that the collective memory of the people remained vibrant and accurate. The creation of these belts was a communal, spiritual endeavor, requiring immense skill and patience, reflecting the gravity of the messages they carried.

Masks: Guardians of Health and Spirit

Another profoundly significant, yet often misunderstood, aspect of Haudenosaunee art involves the creation of ceremonial masks. Two primary types exist: the wooden masks of the False Face Society (Ongwe’oñweka) and the woven corn husk masks. Both are central to healing ceremonies and are treated with immense respect and reverence.

The wooden masks are carved from living basswood trees, a process accompanied by specific rituals and tobacco offerings to the tree spirit. Each mask possesses unique features—twisted noses, pursed lips, exaggerated eyes—reflecting the individual spirits they represent, often those encountered in dreams or visions. These masks are not mere representations but are believed to embody powerful healing spirits, primarily used by members of the False Face Society to cure ailments, drive away disease, and restore balance within the community. Due to their sacred nature, their creation, use, and display are governed by strict protocols. Non-Indigenous acquisition or display of these masks is widely considered cultural appropriation and deeply disrespectful by the Haudenosaunee, who view them as living spiritual entities rather than art objects for public consumption.

Corn husk masks, by contrast, are woven from braided and coiled corn husks. These lighter masks are associated with agricultural spirits and are often used in seasonal ceremonies, particularly those celebrating the harvest. They represent benevolent spirits who ensure the fertility of the crops and the well-being of the community. While also ceremonial, they are generally less restrictive in their handling and display than their wooden counterparts, serving as a reminder of the Haudenosaunee’s deep connection to the earth and their reliance on agricultural cycles.

Beadwork: A Floral Symphony of Identity

Haudenosaunee beadwork, particularly the distinctive "raised beadwork," is instantly recognizable and a testament to artistic innovation and cultural adaptation. While Indigenous peoples used natural materials like quills and shells for adornment for centuries, the introduction of glass beads through trade with Europeans revolutionized the art form. Haudenosaunee artists quickly adopted these new materials, developing a unique three-dimensional style where beads are sewn onto fabric (often velvet or broadcloth) in layers, creating a sculpted, almost sculptural effect.

Floral motifs dominate Haudenosaunee beadwork, drawing inspiration from the abundant plant life of their ancestral lands. Strawberries, corn, vines, leaves, and various blossoms are rendered with vibrant colors and intricate detail. These designs are not merely decorative; they often carry symbolic meanings related to fertility, sustenance, and the interconnectedness of all living things. Beadwork adorns everything from clothing, moccasins, and bags to pincushions and picture frames, often created as gifts or for personal use.

"Every bead sewn is a prayer, a connection to our ancestors," says Kahonwes, a younger Mohawk beadworker. "When I create a piece, I’m thinking about the person who will wear it, the stories it might tell, and the spirit of the plants that inspire the design. It’s a living tradition, always evolving but always rooted in our heritage." This art form continues to thrive, with contemporary artists pushing boundaries while honoring traditional aesthetics, showcasing their work in galleries and powwows alike.

Basketry and Woodcarving: Practical Beauty, Enduring Craft

The Haudenosaunee have long been master artisans of the natural world, transforming raw materials into objects of both beauty and utility. Basketry, particularly splint basketry made from pounded ash wood, is a hallmark of their craft. The process involves harvesting black ash trees, pounding the logs to separate the growth rings into long, pliable splints, and then weaving these into baskets of various shapes and sizes. These baskets served diverse purposes: collecting berries, storing food, carrying goods, and even processing corn. Sweetgrass, with its distinctive vanilla-like scent, is often incorporated into baskets for ceremonial purposes or as decorative elements, adding another layer of sensory richness.

Woodcarving, too, remains a vital tradition. Beyond the sacred masks, everyday items like ladles, spoons, bowls, and combs were expertly carved, often featuring animal motifs or clan symbols. The most iconic wood-carved item, however, is the lacrosse stick. Lacrosse, known as "The Creator’s Game" to the Haudenosaunee, is more than a sport; it is a spiritual practice, a medicine game played for healing and to honor the Creator. Each stick, traditionally carved from a single piece of hickory, is a work of art and a sacred instrument, embodying the strength and spirit of the game.

Continuity and Challenges in a Modern World

The journey of Haudenosaunee traditional arts through centuries of colonization, forced assimilation, and cultural disruption is a testament to the indomitable spirit of the people. Despite immense pressures, the knowledge and skills were preserved, often in secret, passed down from generation to generation within families and communities. Elders played a crucial role in safeguarding these traditions, ensuring that the wisdom embedded in each art form was not lost.

Today, Haudenosaunee traditional arts are experiencing a vibrant renaissance. Community workshops, cultural centers, and tribal schools are actively teaching younger generations the techniques and philosophies behind these crafts. Artists are not only preserving ancestral methods but also innovating, blending traditional forms with contemporary expressions. This revitalization is crucial not only for cultural preservation but also for economic empowerment, as artists can sustain themselves through their craft.

However, challenges persist. Cultural appropriation, where non-Indigenous individuals or companies exploit Indigenous designs without understanding or respecting their cultural context, remains a concern. Authenticity and the protection of Indigenous intellectual property are ongoing battles. Yet, the Haudenosaunee continue to assert their sovereignty over their cultural heritage.

The Living Legacy

The traditional arts of the Haudenosaunee are far more than museum pieces; they are dynamic expressions of a living culture. They are the threads that bind generations, the visual language that conveys history and spirituality, and the tangible evidence of a profound connection to the land and the Great Law of Peace. Each bead, each weave, each carved form resonates with the echoes of ancestors, speaking volumes about resilience, identity, and the enduring power of creation.

As the smoke from the ceremonial fires rises, and the rhythmic beat of the water drum fills the Longhouse, one can see and feel the artistry everywhere – in the regalia worn by dancers, in the wampum belts displayed with reverence, in the very structure of the community. It is a powerful reminder that true art is not just seen; it is experienced, felt, and lived, embodying the very soul of a people. The Haudenosaunee traditional arts stand as a beacon of cultural survival, a testament to the profound beauty and wisdom that flows from a people deeply rooted in their heritage.